Article type: Original Research

2 October 2025

Volume 47 Issue 2

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 5 March 2025

REVISED: 13 August 2025

ACCEPTED: 14 August 2025

Article type: Original Research

2 October 2025

Volume 47 Issue 2

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 5 March 2025

REVISED: 13 August 2025

ACCEPTED: 14 August 2025

![]() Exploration phase: Improving transition planning in residential out-of-home care

Exploration phase: Improving transition planning in residential out-of-home care

Affiliations

1 Health and Social Care Unit, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic. 3000, Australia

2 Present address: Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation, School of Public Health and Social Work, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Qld 4059, Australia

3 Department of Social Work, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic. 3073, Australia

4 MacKillop Family Services, Melbourne, Vic. 3205, Australia

Correspondence

* Hayley Wainwright

Contributions

Hayley Wainwright - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Helen Skouteris - Critical revision

Angela Melder - Critical revision

Sarah Morris - Acquisition of data, Critical revision

Nick Halfpenny - Critical revision

Heather Morris - Study conception and design, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Hayley Wainwright1 *

Helen Skouteris1

Angela Melder1,2

Sarah Morris3

Nick Halfpenny4

Heather Morris1

Affiliations

1 Health and Social Care Unit, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic. 3000, Australia

2 Present address: Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation, School of Public Health and Social Work, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Qld 4059, Australia

3 Department of Social Work, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic. 3073, Australia

4 MacKillop Family Services, Melbourne, Vic. 3205, Australia

Correspondence

* Hayley Wainwright

CITATION: Wainwright, H., Skouteris, H., Melder, A., Morris, S., Halfpenny, N., & Morris, H. (2025). Exploration phase: Improving transition planning in residential out-of-home care. Children Australia, 47(2), 3054. doi.org/10.61605/cha_3054

© 2025 Wainwright, H., Skouteris, H., Melder, A., Morris, S., Halfpenny, N., & Morris, H. This work is licensed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Abstract

This mixed-methods study explored how transition planning is implemented in Victoria, Australia, from the perspectives of young people, residential out-of-home care staff and cross-sector staff. Data were collected from 46 interviews, 105 surveys and 95 transition plan documents. The study explored who participates in transition planning, how it is conceptualised and implemented in practice and differences across demographic contexts. Findings revealed that young people receive support from multiple organisations, with Child Protection (the government agency responsible for child welfare) and the residential care provider consistently involved. However, interpretations of who holds primary responsibility varied across the workforce, and young people’s participation typically occurred indirectly through informal conversations rather than through formal goal-setting processes. Transition planning was conceptualised as a task-oriented process focused on securing housing, meeting basic needs and developing life skills, with significant variation in how it was understood across demographic contexts. Implementation was shaped by system-driven transition plan documentation, supplemented with multiple documents and bespoke tools to address young people’s diverse needs. Young people typically exited residential care between the ages of 16 and 17 years, with limited long-term pathways out of care. Their readiness to leave residential care was determined by the Child Protection agency, which holds legal guardianship of young people in residential care to age 18. The findings highlight the need for policy and practice improvements to: (1) strengthen role clarity; (2) develop a shared understanding of core transition planning components; and (3) align transition planning processes with young people’s developmental readiness. Further research is needed to explore how transition planning can be enhanced to better meet young people’s diverse needs.

Keywords:

care leavers, innovation, out-of-home care, plan, residential care, transition from care.

Introduction

In Australia, approximately 45,000 children and young people are in out-of-home care (OOHC), with 4,300 residing in residential care, which is a group home composed mostly of young people aged 12–17 years (AIHW, 2024). Young people must leave residential care no later than their 18th birthday because their child protection order expires and the ’state’s guardianship responsibility ends (Mendes et al., 2023a; O’Donnell et al., 2020a). The process of preparing young people to leave residential care is referred to as ‘transition planning’ and is recognised as a challenging process worldwide (Munro & Simkiss, 2020; Storø, 2021). In Australia, while each state and territory has its own OOHC legislation, policies and programs, there is a federal government expectation that young people will receive transition planning (Mendes & McCurdy, 2019). This is a goal setting process designed to identify and address young people’s needs, plan for future housing and build readiness to live independently (Mendes et al., 2023b).

There is general agreement on the factors that support successful transition planning, including: actively involving and centring the voices of young people (Häggman-Laitila et al., 2020; Mendes et al., 2023b); gradual and supported planning (Munro & Simkiss, 2020); access to social support (O’Donnell et al., 2020b); and extended care until at least 21 years of age (Courtney et al., 2018; Mendes et al., 2023a). Acquiring life skills, engagement in education (Goulet et al., 2024) or employment (Furey & Harris-Evans, 2021) and appropriate housing (García-Alba et al., 2022) are also critical. Connection to Culture and Community is also essential for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people (Mendes et al., 2022; Raman et al., 2017) as well as multi-faith and multi-cultural young people (McMahon et al., 2021). More broadly, young people in care constitute a heterogeneous cohort with unique transition needs and challenges shaped by gender, age, geographical location, disability, cultural identity and early childhood experiences (Cheng et al., 2023; Mendes et al., 2013, 2022; Milne et al., 2021; Purtell, et al., 2021).

Relational factors are essential for successful transitions from care, including clearly defined professional roles that promote continuity and consistency (Browning, 2015). Trusting, supportive relationships with legal guardians can enhance young people’s involvement in decision making (Venables et al., 2025), while consistent relationships with residential carers are vital in preparing young people for independent living (Holt & Kirwan, 2012). Despite this established knowledge on what contributes to successful transitions from care, how transition planning is implemented in practice remains poorly understood.

In the State of Victoria, Australia, a ‘Care and Transition Plan’ (transition plan) was implemented in 2012 (Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH), 2012). This plan is designed to be completed regularly for young people in care between the ages of 15 and 17 years to identify and address ’their needs across seven domains: health; emotional and behavioural development; education, training and employment; family and social relationships; identity; social presentation; and self-care skills (https://www.cpmanual.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/15+Care&Transition Form.pdf). Additionally, young people who are in OOHC on, or after, their 16th birthday, and are subject to one of four child protection orders, are eligible for transition-from-care support from Better Futures. Better Futures includes flexible funding to support young people’s transition from care (e.g. rent) and case work support from age 15 years and 9 months to their 21st birthday (DFFH, 2024; Mendes et al., 2023a). Government guidelines provide broad directions for transition planning, stating that case managers hold primary responsibility for transition planning in collaboration with the care team (the network of professionals supporting a young person), and that young people should actively participate in developing and reviewing their plans (DFFH, 2012, 2024).

Despite the positive intent of existing policies and practices, research indicates that transition planning often fails to achieve its goal of preparing young people for independent living (Commission for Children and Young People (CCYP), 2020; McDowall, 2012; Storø, 2021). Moreover, there is limited evidence on how to implement transition planning effectively (Alderson et al., 2023; CCYP, 2020), highlighting a significant knowledge gap. To address this gap, the aims of this study were to explore:

- Who is involved in the implementation of transition planning and how, including differences across demographic contexts;

- How recipients (young people) and deliverers (service providers and cross-sector staff) conceptualise transition planning, including differences across demographic contexts; and

- How the transition planning process is implemented in residential care, including differences across demographic contexts.

Methods

Ethics

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 39433). The research formed part of a broader project in partnership with MacKillop Family Services (MacKillop), which is named with their permission. The risk of re-identification of young people and staff was minimised through several safeguards. All quotes were de-identified and not linked to demographic characteristics such as gender, geographic location or recruitment source.

Participation was voluntary, and all participants received a plain-language explanatory statement, gave informed consent and were provided with a list of support services. Additional safeguards were in place for young people, including the option to bring a support person, pause or withdraw at any time, and a reminder at the conclusion of the interview to contact a trusted adult or support service if needed. The interview and survey questions were co-developed with a researcher with lived experience of care (SM) to ensure safety. Interviews were semi-structured to allow young people to focus on topics they felt comfortable discussing and in-person interviews included the option to use sensory objects (such as playdough or squeeze balls) to support regulation. All interviews were conducted by the first author (HW), a trained frontline practitioner with experience working with young people using trauma-informed approaches. All participants were no longer in care and expressed a strong desire to contribute to system improvement. See Participants and recruitment for further detail.

Approval to access transition plan documents was granted by DFFH, as the legal guardian for young people in care, alongside written organisational consent from MacKillop. As the documents were collected for routine service delivery, young people did not provide individual consent. All documents were de-identified by MacKillop prior to sharing with HW via a password protected file exchange. See Data collection section for further detail on transition plans.

Study design

This study adopted a multi-phase mixed-methods design to explore the research aims. Table 1 outlines the data collection phases and measures that addressed each aim.

Table 1. Data source used to address each aim

| Research aim |

Data collection phases and measures |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Transition plan (Phase 1) |

Survey (Phase 2) |

Interview/focus group (Phase 3) |

||

| (1) | Who is involved in the implementation of transition planning and how, including differences across demographic contexts |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| (2) | How do recipients (young people) and deliverers (service providers and cross-sector staff) conceptualise transition planning, including differences across demographic contexts |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

| (3) | How is the transition planning process implemented in residential care, including differences across demographic contexts |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Participants and recruitment

Three participant groups were recruited to gain in-depth insights from both recipients and deliverers of transition planning: (1) MacKillop staff; (2) care-experienced young people; and (3) cross-sector staff. Additionally, 95 transition plans for 61 young people, were included in the analysis. The number of participants by data source is reported in Table 2.

The following sections describe the recruitment and characteristics of each participant group, with key participant demographics reported in Table 3. Full demographic data are provided in Supplementary Material 1.

Table 2. Number of participants recruited across each data source

| Participant group and places of recruitment |

Data source |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Transition plans |

Survey |

Interview |

Focus group |

|

| MacKillop |

95 |

102 |

11 |

11 |

| Care-experienced young people |

2 |

6 |

||

| MacKillop |

2 |

2 |

||

| CREATE FoundationA |

3 |

|||

| Better Futures ProvidersB |

1 |

|||

| Cross-sector staff |

12 |

7 |

||

| Disability program |

7 |

2 |

||

| Multi-cultural and multi-faith programs |

5 |

|||

| Education programs |

4 |

1 |

||

| Total |

95 |

104 |

29 |

18 |

ACREATE Foundation is the national consumer body representing children and young people in out-of-home care.

BBetter Futures providers are Victoria’s transition-from-care support service for young people up to age 21.

MacKillop staff

The primary setting was MacKillop in Victoria, Australia, which supports approximately 130 young people across 49 residential care homes at a time. All staff who work with young people transitioning from residential care were invited to participate in an interview and/or survey. Staff were recruited using the following purposive and snowballing sampling strategies (Palinkas et al., 2015): (1) leaders shared the study invitation multiple times with staff; (2) leaders were contacted in areas of low staff representation with the option of a focus group; and (3) participants shared the invitation with colleagues. MacKillop staff roles were categorised in two ways to explore the research aims: (1) by specific role title; and (2) by whether the role was based ‘in the home’ (e.g. Residential Carer or House Supervisor), or in an ‘office-based’ role outside the home (e.g. Case Manager or Leadership). The role mapping used for these categories is provided in Supplementary Material 2. Throughout this manuscript, the term ‘MacKillop staff’ is an aggregate descriptor for all MacKillop participants across ten roles, unless otherwise specified (Supplementary Material 1, Table S1).

Care-experienced young people

Young people aged 18–24 who had transitioned out of residential care were invited to participate in the research via interview and/or survey. They were recruited using purposive sampling strategies (Palinkas et al., 2015) through multiple organisations to increase the sample size and ensure a diversity of perspectives: (1) MacKillop staff shared the invitations with young people who had left residential care; (2) the CREATE Foundation distributed the invitation to members of their Youth Expert Advisory Group; and (3) Better Futures service providers distributed the invitation to their networks of care-experienced young people (Table 2).

Recruitment was conducted through trusted networks to ensure that young people had access to appropriate support if they needed. To promote meaningful participation, young people were offered flexibility in how they participated. They could choose their preferred interview mode (Zoom, phone or in person), time and were given space to discuss what felt important to them. The flexible interview modality enabled young people in regional and rural locations to participate, and for young people to participate in a way that felt safe and appropriate for them. All young people were provided with a $50 gift card for interviews and a $30 gift card for surveys.

Cross-sector participants

Staff who participate in the delivery of transition planning, but are external to MacKillop, were invited to participate to ensure a comprehensive exploration of the research aims. Hereafter, these staff are referred to as cross-sector staff. Eligible participant groups were identified through the transition plans, interviews with staff and consultation with a key partner at DFFH. Cross-sector staff were invited to participate via interview or focus group and were recruited using the following purposive sampling strategies (Palinkas et al., 2015): (1) DFFH key partner shared the study information; (2) key contacts within cross-sector teams promoted the study; and (3) participants shared the invitation with colleagues. See Table 3 for the number of cross-sector participants by program focus. Throughout this manuscript, the term ‘cross-sector staff’ is an aggregate descriptor for all cross-sector participants across four organisations (Supplementary Material 1, Table S3).

Table 3. Participant demographics

| Variable |

MacKillop staff (n = 124) |

Cross-sector staff (n = 19) |

Care-experienced young people (n = 8) |

Young people in care – transition plans (n = 95) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

# |

% |

# | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female |

89 |

72 | 14 | 74 | 4 | 50 | 42 | 44.2 |

| Male |

34 |

27 | 3 | 16 | 1 | 13 | 49 | 51.6 |

| Prefer not to say |

1 |

1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 13 | ||

| Non-binary | 2 | 25 | 1 | 1.1 | ||||

| Other | 1 | 5 | ||||||

| Not reported | 3 | 3.2 | ||||||

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | ||||||||

| Yes |

5 |

4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 18 | 18.9 |

| No |

115 |

93 | 19 | 100 | 7 | 87 | 72 | 75.8 |

| Prefer not to say |

4 |

3 | ||||||

| Not reported | 5 | 5.3 | ||||||

| Born in Australia | ||||||||

| Yes |

93 |

75 | 16 | 84 | 7 | 87 | ||

| No |

31 |

25 | 3 | 16 | 1 | 13 | ||

| Lived experience of being in out-of-home care | ||||||||

| Yes |

7 |

6 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| No |

115 |

93 | 18 | 95 | ||||

| Prefer not to say |

2 |

2 | ||||||

| RoleA | ||||||||

| Work in the home (e.g. Residential Carer) |

75 |

60 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Work office based (e.g. Case Manager) |

49 |

40 | 19 | 100 | ||||

| Years’ experience |

Median (IQR) |

Mean (SD) | ||||||

| Out-of-home care system |

4.5 (2.5–8.8) |

6.29 (2.68) | ||||||

| Current organisation |

3.00 (1.0–5.0) |

3.86 (2.59) | ||||||

| Mean age (SD) | ||||||||

| Current | 19.88 (2.1) | |||||||

| When transitioned from care | 16.88 (0.64) | |||||||

| When plan completed | 15.7 (0.74) | |||||||

AMacKillop staff members’ roles were categorised in two ways: (1) role name; and (2) work in the home with young people, or in an office-based role. See Supplementary Material 2 for the role mapping.

Data collection

Framework and reporting guidelines

The Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework guided the recruitment, data collection and analysis. This four-stage implementation process framework provides a structured approach to enhancing the implementation and quality of services by exploring how contextual factors influence implementation (Aarons et al., 2011). The study focused on the ‘Exploration’ phase of the framework, which involves identifying the cause of the issue (e.g. poor transition from care outcomes), key participant needs and contextual factors that may influence implementation. The Good Reporting of a Mixed Method Study (GRAMMS) checklist (O’Cathain et al., 2008), which provides criteria to promote comprehensive reporting of mixed-methods research, was used to guide reporting of the findings (Supplementary Material 3).

Phase 1: Transition plans

The first phase involved a document analysis of transition plans (n = 95). The purpose of this analysis was to identify who is involved in transition planning and how contributors participate in the plan development. While this phase provided insight into Research Aim 1, it did not provide insight into how planning processes are enacted in practice nor how young people are engaged. These gaps informed the design of subsequent phases.

All plans related to young people currently in care (e.g. open cases) at the time of data collection. No identifying information about young people was accessed or retained during the analysis. Data were extracted from each transition plan based on the fields included in the document template. Extracted data were managed in Microsoft Excel and SPSS. See Supplementary Material 4 for a full list of extracted fields.

Phase 2: Survey

Survey instruments were developed to gather diverse perspectives from those who deliver (MacKillop staff) and receive (care-experienced young people) transition planning. Specifically, it aimed to capture broader insights than feasible via interviews alone and to examine patterns and associations across demographic contexts. The survey questions were informed by the transition plans, a literature scan and the EPIS framework (Aarons et al., 2011). The survey questions (and interview/focus group questions) were reviewed by the Aboriginal Service Development team at MacKillop to ensure culturally relevant questions for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander participants. The survey also included a measure of transition planning co-production developed by Park et al. (2022), containing the following items: ‘I am not aware of my independent living plan’; ‘I was not involved in the development of my independent living plan’; ‘I was involved in the development of my independent living plan but did not lead it’; and ‘I led the development of my independent living plan’. The items were adapted to ensure language was relevant; for example, ‘independent living plan’ was replaced with ‘transition plan.’

The survey was open from April to September 2024. Quantitative data were imported into SPSS and open-text responses were imported into NVivo. Survey questions are reported in Supplementary Material 5.

Phase 3: Interviews and focus groups

The overarching purpose of the interviews and focus groups was to explore all research aims in depth, across a range of perspectives. The interview and focus group questions were informed by insights from the transition plan analysis and survey results. The interview and focus group schedule explored demographic information, the core components of transition planning, how it is implemented and suggestions for change (see Supplementary Material 6 for the questions). Participants were offered a choice of participation mode (Zoom, telephone or in person), which supported accessibility and participant comfort. Interview and focus groups were conducted between April and October 2024 via Zoom (n = 23), telephone (n = 6) or in person (n = 5) and ranged in length from 52 to 126 minutes (mean = 82 min). All interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and then transcribed.

Data analysis

Quantitative and qualitative data were analysed separately, then integrated to provide a comprehensive understanding of how transition planning is conceptualised and implemented in residential care. The analysis was informed by the Exploration phase of the EPIS framework, with a focus on identifying convergent and divergent perspectives across data sources regarding each aim. Given the low survey response rate from care-experienced young people (n = 2), their survey data were integrated with interview responses and reported descriptively.

Document analysis

A quantitative document analysis approach was applied to the transition plans to explore who participates in transition planning and how. Structured fields, such as demographics and checklists, were extracted to calculate frequencies. Open-text fields (e.g. role of staff member completing the plan) were coded and categorised into predefined role types (e.g. Case Manager), allowing for quantitative analysis (e.g. proportion of plans authored by Case Managers) of the transition plan content. The quantitative analysis techniques are described below.

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative thematic analysis of all data sources was conducted via inductive and deductive coding techniques. The deductive coding structure was established a priori in line with the survey and interview schedule and inductive coding was used to identify emergent knowledge. The inductive coding was completed in line with Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six phases, which include: (1) reading all transcripts, survey and transition plans to become familiar with the data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) grouping codes into potential themes; (4) refining and reviewing themes; (5) clarifying and naming each theme; and (6) combining analysis and data to present findings. All open-text survey data and interview transcripts were coded by the first author (HW) and five interview transcripts were double coded by a second researcher to enhance reliability; all discrepancies were resolved through discussion between these two authors.

Verbatim quotations are referenced using the following format: MacKillop staff (MAC_participant number), cross-sector staff (CS_participant number) and young people (YP_participant number).

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative data from the transition plans and survey were analysed using SPSS. Frequencies were calculated for categorical variables (e.g. gender). Mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) were computed for normally distributed numerical variables (e.g. age), and medians and interquartile ranges were used for non-normally distributed numerical data (e.g. years of experience). To explore associations between variables, several statistical tests were conducted: Chi-square tests of independence were used to examine relationships between categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U-test (2 variables) and Kruskal–Wallis H-test (3+ variables) were used for examining whether the median differences in numerical variables were statistically significant across categorical groups.

Results

Who is involved and how?

This section addresses Research Aim 1, who is involved in transition planning, and how involvement and responsibilities vary across young people and staff contexts.

Inconsistent role clarity and limited involvement of key staff

Survey findings

MacKillop staff reported that a wide range of roles are involved in transition planning, with an average of 10.2 roles (SD = 3.87), identified per respondent. Leadership staff identified the highest number of roles (M = 12.29, SD = 2.64), while Case Managers identified the fewest (M = 9.55, SD = 4.30); however, these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). In contrast, the two young people surveyed identified an average of 5.5 roles involved in their planning, suggesting a narrower experience of who was involved in their planning.

Staff also ranked the level of responsibility assigned to each role (Table 4). Office-based staff (e.g Case Managers) were more likely to attribute greater responsibility to House Supervisors (U = 79, p = 0.011), whereas home-based staff (e.g. Residential Carers) attributed greater responsibility to Housing Providers (U = 29, p = 0.04). These findings indicate that while staff agree that transition planning is a collaborative process, varied perceptions of roles and responsibilities may contribute to inconsistent implementation.

Table 4. Mean ranking of most and some responsibility that each role has over the transition planning process

AOD, Alcohol and other drugs; NDIS, National Disability Insurance Scheme.

| Role |

Mean responsibilityA

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

Most (SD) |

Some (SD) | |

| Child protection |

2.8 (2.1) |

3.1 (1.8) |

| Case Manager (MacKillop) |

2.8 (1.8) |

3.5 (2.1) |

| Young person |

3.2 (2.6) |

2.3 (1.3) |

| Residential Care Worker |

3.6 (2.0) |

3.5 (2.1) |

| House supervisor |

3.8 (1.5) |

3.1 (1.7) |

| Case Manager (other services) |

3.8 (1.7) |

2.9 (2.0) |

| Therapeutic Practitioner |

3.9 (1.8) |

3.0 (1.7) |

| Coordinator |

3.9 (2.3) |

2.7 (1.6) |

| Aboriginal organisation |

4.0 (2.5) |

2.9 (2.0) |

| Principal Practitioner |

5.0 (2.5) |

3.5 (1.7) |

| Family |

5.0 (2.4) |

3.4 (1.9) |

| Housing provider |

5.4 (2.6) |

3.3 (1.9) |

| Education provider |

6.9 (3.0) |

3.8 (2.4) |

| AOD provider |

7.7 (4.9) |

4.3 (2.7) |

| Employment provider |

8.8 (1.5) |

3.4 (1.9) |

| Other (Lead Tenant ProgramsB, NDIS, Youth Justice, Mentor, Religious Groups, Youth Outreach Worker) |

– |

8.0 (7.0) |

AA lower mean equates to a higher ranking.

BLead Tenant Programs are housing models in which young people are supported by adult volunteer tenant/s, typically while still on a child protection statutory order.

Transition plan findings

In contrast to survey findings, analysis of transition plans identified an average of 3.79 (SD = 2.6) care team members per plan, spanning 33 distinct roles. Across all plans, there were 260 total references to care team members. Supplementary Material 7, Table S1 reports the frequency and proportion of these references by role. The most commonly listed roles were education (10.4%, 27/260), disability (8.8%, 23/260), mental health (7.3%, 19/260), Child Protection (6.9%, 18/260), Therapeutic Practitioners (6.5%, 17/260) and House Supervisors (6.2%, 16/260). Residential Carers were listed as care team members in only 1.9% (5/260) of transition plans. Parental involvement was also low, with mothers included in 19% (18/95) and fathers in 1% (1/95) of transition plans.

While this reflects broad service involvement on paper, plan development was typically concentrated among a small number of staff (M = 1.23, SD = 1). Across all plans, there were 116 total references to staff involved in developing the plan. Supplementary Material 7, Table S2 reports the frequency and proportion by role. The most commonly listed roles were MacKillop Case Managers (25.0%, 29/116), House Supervisors (20.7%, 24/116), Child Protection (14.7%, 17/116) and Residential Carers (14.7%, 17/116). Notably, despite being rarely listed as care team members, Residential Carers authored 8.4% (8/95) of plans, highlighting variability in Residential Carers’ involvement in planning.

These findings mirror survey data, suggesting that while transition planning formally involves multiple stakeholders, plan development is concentrated among a small subset of roles. This centralisation may shape both the planning process and young people’s opportunities for meaningful participation.

Interview findings

Interviews confirmed that transition planning is a collaborative process led by Case Managers and Child Protection, and involves multiple roles and sectors, with variations depending on young people’s needs. Both staff groups described Case Managers and Child Protection staff as the central actors in developing the transition plan and facilitating referrals to housing and external services. However, as young people approach 18 years of age or transition to semi-independent housing, responsibility shifts from residential care Case Managers to Case Managers of transition-from-care programs such as Better Futures, Targeted Care Packages (a program that provides flexible, tailored support typically for young people with higher needs) and semi-independent housing models. The most identified roles, and how they contribute to transition planning, are summarised in Supplementary Material 8.

Case Managers described their role as translating young people’s broad aspirations (e.g. education, employment and housing) into actionable steps as reflected in one MacKillop staff member’s account:

What we do is we look at what the actual plan is, and we set goals and build strategies around each sort of milestone or each goal. If a young person doesn’t know how to build a bank account, we’ll make sure that they’ve got a bank account and they know where to access that and what the process is. (MAC_05)

In contrast, Residential Carers were described as playing a key relational and developmental role yet having limited involvement in formal transition planning. Their contributions were often indirect, relayed through House Supervisors who attended care team meetings. As one MacKillop staff member noted:

… they [residential carers] may not be responsible for actually building the document, but they have an input in it. They may not know they do, but they do. (MAC_06)

These accounts diverge between survey and plan data, which attributed substantial responsibility to Residential Carers.

Overall, while many staff and services support transition planning, formal processes are driven by a small number of staff. Inconsistent role clarity reflects a gap between the everyday support provided to young people and structured transition planning processes. These patterns of role variability and limited relational integration also shape how young people are engaged in transition planning, as explored in the following section.

Young people’s participation in transition planning is variable and often indirect

Survey findings

Young people’s involvement in transition planning varied across data sources. Among MacKillop staff surveyed who answered this question, the majority (88.8%, 79/89) indicated that young people are ‘involved in, but do not lead’ their planning. A small proportion of staff reported that young people were either ‘not aware of it, or not involved’ (4.5%, 4/89) or ‘involved and lead it’ (5.6%, 5/89) and one participant was unsure. Responses differed by staff role. Home-based staff reported polarised views, with equal proportions (6.3%, 4/64) indicating that young people were either not aware of transition planning or had led it. In contrast, both care-experienced young people surveyed reported leading their transition planning, yet neither received a copy of their plan. This highlights inconsistencies in how young people’s involvement is perceived by staff and young people themselves.

Transition plan findings

Transition plan data also reflected variability in young people’s participation. Of the 95 plans, 68.4% (65/95) reported young people as having participated to some degree. However, most of these (71.4%, 68/95) were described as ‘partly involved’, typically through indirect or informal conversations rather than direct engagement in planning. In 31.6% (30/95) of plans, no participation was recorded, often due to refusal, absence from placement, or sleep-related factors. Young people’s participation also varied by author. They were more likely to be recorded as involved when Case Managers completed the plan (77.6%, 45/58) compared with Residential Carers (50.0%, 4/8) and House Supervisors (33.3%, 3/9), though these differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.093).

Interviews findings

Interviews reinforced these findings. Staff across both staff groups reported that young people rarely led their own planning and were more commonly engaged through informal interactions. While planning sometimes occurred through structured forums such as care team meetings, MacKillop staff described indirect methods as more typical:

… their voice is heard through other means … a conversation with a certain worker that is then that are then communicated to the care team … unfortunately, it is that instead of direct conversations. (MAC_01)

Staff acknowledged that young people’s involvement should be more direct and collaborative, but felt some young people were unreceptive to formal processes. In response, staff adapted by using informal approaches to elicit input:

The carer sits down with it and fills it out for them … I think that most of the time that the young person’s choice, like the carer will say do you want to sit down and do this, and then they’ll be like f*** off. But … we really should be sitting down with the young person and like let’s do this together. (MAC_04)

As a result of the informal participation, both staff groups reported that young people lacked awareness that they had a documented transition plan. As one cross-sector staff member reflected:

A lot of young people do not know if they have had a transition plan. I do not think that they feel informed in the process. I do not think it meets any kind of basic principles of youth participation or agency or control over one’s own life. (MAC_19)

Similarly, the young people described feeling involved in decisions about housing or goals but were unaware of a documented plan and had not received a copy of it:

I didn’t even know there was a plan … like a formalised thing. (YP_01)

Staff provided several explanations for this lack of awareness, including that young people do not request the plan and staff may feel uncomfortable sharing it due to its contents. Some also noted that even when young people identified their goals and preferences, these were overridden by system priorities and care team decisions. As one cross-sector staff member explained:

Sometimes young people have their own goals that are not in their best interest or what we assess are not in their best interest … that can just conflict with what the care team are working towards. So, while it is important for them to have their voice heard, it is a hard balancing act. (CS_04)

Overall, findings from all data sources indicate that young people’s participation in transition planning is largely informal and inconsistent. While indirect engagement may enable staff to capture young people’s preferences, it may also limit their agency, awareness and capacity to meaningfully participate in planning processes. These patterns, alongside findings from MacKillop staff and cross-sector roles and responsibilities, inform the discussion of how role clarity, relational practice and young people’s participation can be strengthened.

How transition planning is conceptualised

This section presents findings for Research Aim 2, exploring how young people and staff conceptualise transition planning, and the variations across contexts.

Transition planning conceptualisation varies across workforce roles and young people

Survey findings

Survey data indicated that MacKillop staff predominately conceptualised transition planning as a task-oriented process (Table 5). The most frequently reported components were developing life skills, developing a transition plan and supporting young people’s active participation. ‘Other’ components included connecting young people with leaving care programs such as Lead Tenant and independent living skills programs.

Staff identified a median of 13 components (IQR: 10–15), though 3.9% (4/102) were uncertain about what transition planning involved, highlighting a lack of shared understanding. Conceptualisations varied by demographic factors, including gender, country of birth, role type, regionality and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander identity (Table 6). Staff with a lived experience of care identified significantly more components (H(2) = 6.946, p = 0.031). All other demographic characteristics showed no statistically significant differences in the number of components identified.

Table 5. Frequency and proportion of transition planning components (n = 102)

| Transition plan components |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Support young people to develop living skills (e.g. hygiene, cooking) |

96 |

94.1 |

| Develop a tailored Care and Transition Plan |

92 |

90.2 |

| Support young people to be active participants |

92 |

90.2 |

| Support young people to engage in employment |

91 |

89.2 |

| Support young people to identify their goals |

89 |

87.3 |

| Support young people to engage in education |

85 |

83.3 |

| Start planning at 15 to leave care |

84 |

82.4 |

| Regularly review and update plans |

81 |

79.4 |

| Refer young people to Better FuturesA |

78 |

76.5 |

| Use plans to guide referrals and support |

76 |

74.5 |

| Introduce young people to Better Futures worker |

74 |

72.5 |

| Work with families to support young people’s goals |

69 |

67.6 |

| Develop a Cultural Support Plan (First Nations) |

67 |

65.7 |

| Develop a tailored My Journey to Independent Living planB |

65 |

63.7 |

| Build consistent and trusting relationships with young people |

62 |

60.8 |

| Other |

11 |

10.8 |

| Don’t know |

4 |

3.9 |

ABetter Futures is the name of Victoria’s transition-from-care program, which provides funding and support for care leavers until 21 years old. Government guidelines require staff to refer all young people leaving care at age 15–16 years.

BMacKillop-specific transition plan.

Table 6. Summary statistics and statistically significant associations between demographics and transition planning conceptualisation

This table presents the median number of transition planning components identified by staff, with interquartile range (IQR) and significant associations between staff characteristics and transition planning conceptualisation. Significance at p < 0.05.

| Variable |

Average and variability Median (IQR) |

Statistically significant association with demographics and transition planning components | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Component |

Chi-square test of significance (n = 102) |

|||

|

Role type (binary) |

Outside the home |

13.5 (11–15) |

1. Working with families to support young people’s goals |

χ2(1) = 5.962, p = 0.015 |

|

Inside the home |

12 (9–15) |

|||

|

Regionality |

Major city |

12 (9–14) |

1. Working with families to support young people’s goals 2. Consistent and trusting relationships |

χ2(4) = 13.97, p = 0.007 χ2(4) = 10.53, p = 0.032, |

|

Inner regional |

13 (11–15) |

|||

|

Outer regional |

14 (10.5–15) |

|||

|

Remote |

12.5 (11–12.5) |

|||

|

State-wide |

7 (6–7) |

|||

|

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander |

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander |

11 (9.5–13) |

1. Working with families to support young people’s goals 2. Regularly review and update plans 3. Use plans to guide referrals and support 4. Build consistent and trusting relationships |

χ2(2) = 6.22, p = 0.045 χ2(2) = 8.63, p = 0.013 χ2(2) = 6.90, p = 0.032 χ2(2) = 6.181, p = 0.045 |

|

Non-Indigenous |

13 (10–15) |

|||

|

Prefer not to say |

11 (3.25–12.75) |

|||

|

Born in Australia |

Yes |

13 (10.5–15) |

1. Consistent and trusting relationships |

χ2(1) = 4.32, p = 0.045 |

|

No |

11 (9–15) |

|||

|

Gender |

Male |

12 (9.25–15) |

1. My Journey to Independent LivingA |

χ2(2) = 8.95, p = 0.011 |

|

Female |

13 (10–15) |

|||

|

Lived experience of care |

Yes |

15 (14.25–15.25) |

– |

– |

|

No |

12 (9–15) |

– |

– |

|

|

Prefer not to say |

14 (13–14) |

– |

– |

|

AMacKillop-specific transition plan.

Interview findings

Interviews reinforced a task-focused view of transition planning. MacKillop and cross-sector staff described it as encompassing life skills development (e.g. income, hygiene, cooking), informing young people of their options, supporting engagement in education and employment, securing identification and personal documents, and referring young people to services such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), transition-from-care programs and housing models. Notably, other programs that staff receive training in, including a living skills-based program (HEALing Matters; Monash University, 2022), were not conceptualised as being part of transition planning. In contrast to the survey results, completing the formal transition plan document itself was seldom identified as a key component. Rather, planning was framed as a set of practical tasks to support the move from care into alternative housing.

Transition planning conceptualisation differed based on young people’s demographics and needs. For young people with disability, staff described additional steps such as consulting disability specialists, completing NDIS applications and arranging legal guardianship and/or financial administration. They also described needing to ‘parallel plan’, that is, explore both disability-specific and mainstream service options to ensure appropriate housing and supports were in place prior to leaving care. As one cross-sector staff member described:

If the young person needs a formal guardian or financial administrator, that’s really a key ingredient because, otherwise if they get access to their pension and they use all their funds and they don’t have any finances for the rest of the fortnight. (CS_11)

For multi-faith and multi-cultural young people, planning often involved securing permanent residency or appropriate visas and supporting cultural and/or religious connections. The absence of such supports was seen to heighten risk of exploitation and social exclusion because visa status influences access to income and services. As one cross-sector staff member explained:

We owe it to young people to make sure that we are building that connection to community so they can return safely when they need to, because they are going to find themselves vulnerable … facing exploitation. (CS_15)

For Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander young people, MacKillop and cross-sector staff emphasised the importance of embedding cultural components within transition planning, such as developing Cultural Support Plans and maintaining or restoring connections with Culture, Community, Country and Kin. As one cross-sector staff member reflected

It’s important to continuously be looking at kinship … even if it’s one weekend a month or emails … that connection to family is so important. (CS_05)

Young people viewed transition planning more narrowly. They viewed it primarily as a process where they are required to leave, secure alternative accommodation and build their readiness for independent living. As one young person described:

It’s like buying housing items, working on budgeting and financial things, teaching them how bills work and things like that … putting a plan in place. (YP_03)

While all participants viewed task-oriented components of transition planning as important, many raised concerns that current approaches are insufficient. Across participant groups, there was a shared view that transition planning often leaves young people underprepared for life after care due to expectations for self-sufficiency at an early age.

It was stressful and scary at times … I wish I had some more support with independent living skills from an earlier age. It was a big adjustment to make, and I felt a lot of pressure to be more self-sufficient. (YP_02)

We overwhelmingly hear about the negative outcomes and young people feeling unprepared, very anxious, scared, and worried and a real focus on, like, you have got to pull your bootstraps up and, like, fend for yourself kind of thing. (CS_19)

There was also a shared perception of what constitutes a successful transition. This was described by young people and staff as young people actively participating, moving into stable and affordable housing in their chosen area, possessing sufficient life skills, and having access to ongoing support networks. Conversely, unsuccessful transitions were seen as more common and involved homelessness, limited support networks and being unprepared for independence, as one MacKillop staff member reflected:

It is scary … a lot of our kids … in a few years … are either incarcerated, on the streets, or sadly passed away … it’s those key years, once they exit, the supports leave, the instability of housing. (MAC_20)

Overall, while staff and young people emphasised life skills and securing housing as central, young people understood transition planning more narrowly as the process of physically leaving care. In contrast, staff described a broader set of tasks and service connections. These differences, along with variability in staff perspectives, reflect a lack of shared understanding about the purpose and scope of transition planning, which may contribute to inconsistencies in how it is communicated and implemented in practice.

How transition planning is implemented

This section presents findings for Research Aim 3, examining how transition planning processes are implemented in practice and how processes vary across contexts.

Early initiation of planning is structured around system timelines, not young people’s needs

MacKillop and cross-sector participants reported that transition planning typically begins at age 15 years and 9 months, aligning with compliance requirements and allowing adequate time for referrals, assessments and skill building. Plans are reviewed every 6 months and become increasingly focused on housing as young people approach 18 years old. Table 7 outlines the high-level transition planning process by age group.

Staff described initiating planning conversations at varying ages, including 15, 16 or 17 years old. One MacKillop Case Manager explained:

Like literally the day of their 16th, I bring up my leaving care (transition) plan template. (MAC_06)

Others reported initiating planning earlier, guided by their view that young people are ready to start developing key skills around age 15 years:

So, at 15, we will start the conversations around, do you want a job? Because that is when they are old enough to start looking at part-time employment depending on what is going on with school. (MAC_10)

In contrast, young people typically became aware of transition planning between 16 and 17 years old, often prompted by being told to consider where they would live after care. Their accounts reinforce that, for young people, transition planning is synonymous with moving into alternative housing rather than an ongoing developmental process. This contrasts with staff narratives of early initiation and highlights a disconnect between formal timelines and how young people experience the process.

Table 7. Transition planning process

| Start |

Reviewed

|

15–16 years of age | 16–17 years of age | 17–18 years of age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young people in placement prior to 15 years of age | At 15–16 years of age | Every 3 months, then twice a year |

• Identity documents • Life skills • Income • Identify goals • Assessments and referrals |

• Housing • Life skills • Better Futures referral • Services |

• Increased independence • Better Futures starts • Housing |

| Young people enter placement 15+ years of age | Two weeks after entering MacKillop residential care |

Transition pathways are system-determined and reflect service availability more than young people’s readiness

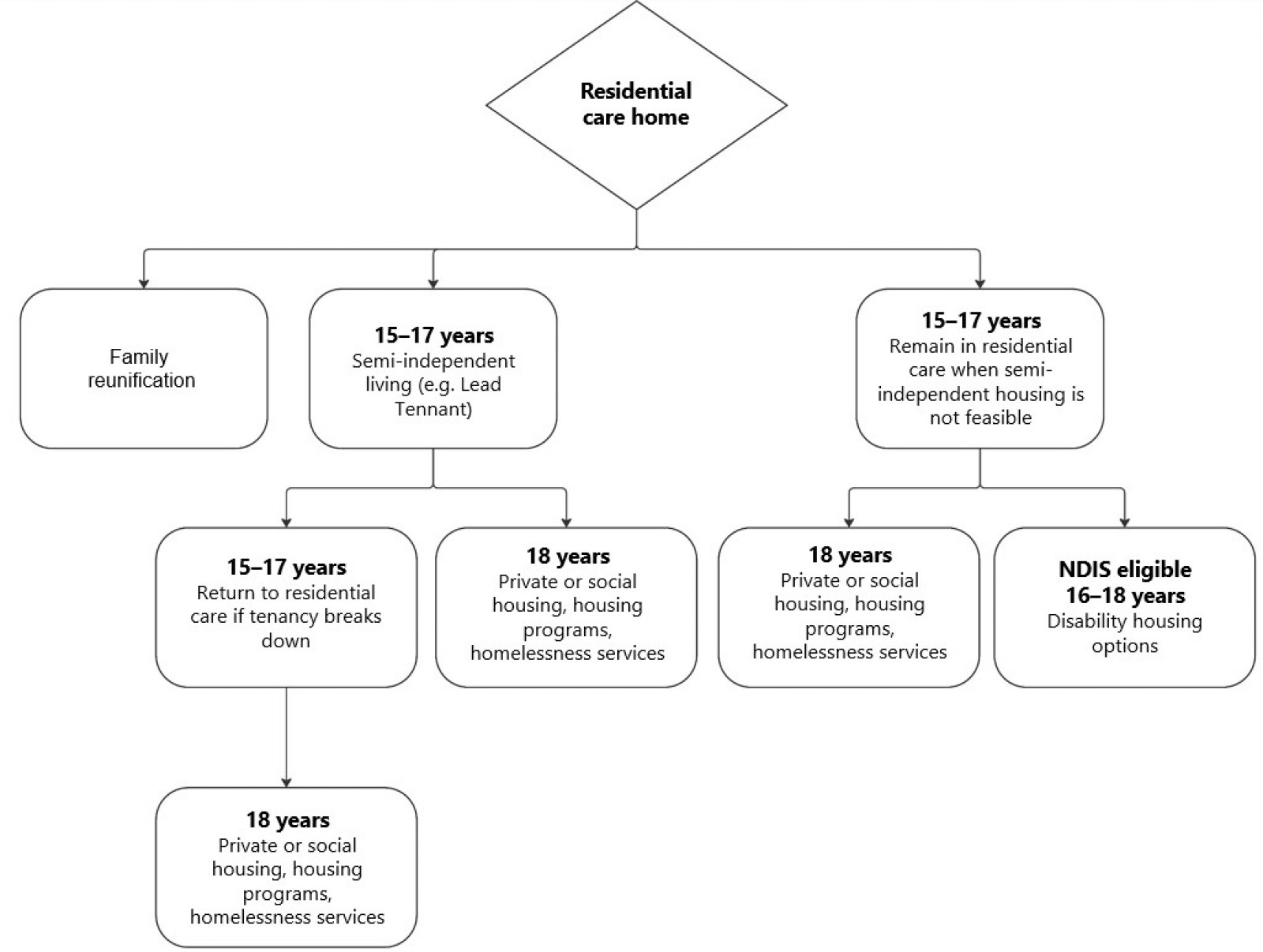

While planning was typically initiated early, young people’s transition pathways are largely shaped by systemic constraints, including service availability, timing and external decisions, rather than their developmental readiness. Four common pathways out of residential care were identified: (1) family reunification; (2) semi-independent housing; (3) independent housing; and (4) disability housing (see Figure 1).

Across participant groups, it was consistently reported that while Child Protection retains legal responsibility until age 18 years, young people are commonly encouraged to exit residential care between ages 16 and 17 years. Most remain in care until age 18 years only if no alternative housing is secured. Additionally, once they exit, most existing formal supports cease, apart from services like NDIS and transition-from-care programs (e.g. Better Futures).

MacKillop and cross-sector staff reported that decisions about when young people transition from care are largely determined by Child Protection, rather than guided by young people’s developmental readiness or preferences. Readiness was typically defined in narrow, practical terms such as being able to cook, demonstrating engagement with staff, attending education and having income. These decisions were seen as driven more by system pressures than by young people’s needs. As one MacKillop staff member noted:

Her readiness is sort of irrelevant because of her age. (MAC_22)

Another reflected on the consequences of this practice:

I had a young person that was forced into independence when she was not ready, she had no confidence in herself she did not want to be alone. She was really scared. (MAC_11)

This system-driven approach was also reflected in formal processes such as the Child-Protection-led ‘leaving care panel’, which is commonly convened for young people aged 16 years and over to assess readiness and to allocate services. While the panel includes representatives from Child Protection and external agencies (e.g. housing, Better Futures, NDIS services), staff viewed it as driven by system needs, rather than young people’s needs. One MacKillop staff member likened it to an auction, critiquing the narrow criteria used to assess readiness:

I was like, are you auctioning these kids off? Child Protection will be like, oh this is Jane, Jane is 17, Jane has her documents, knows how to cook a few meals, knows how to clean a little bit, doesn’t have extreme behaviours … and then people will be like, oh we’ll take her. (CS_02)

These findings highlight how transition pathways are frequently determined by administrative timelines and system capacity, rather than by young people’s readiness, participation or preferences.

Figure 1. Common pathways out of residential care

Step-down pathways are viewed as ideal but are inequitably accessed

Participants across groups identified ‘step-down’ pathways, such as Lead Tenant, as the preferred model for transitioning from care. These models allow young people to gradually build independence with lower levels of support, while remaining connected to Child Protection and Case Managers. Staff and cross-sector participants expressed a strong desire to ‘get kids out [of residential care] as soon as possible’ (MAC_16), motivated by concerns about the risks and limitations of residential care and the belief that earlier transitions offer a critical window to foster independence. However, participants also highlighted that semi-independent housing options are short-term, with tenancies ceasing at 18 years old (or, in rare cases, 19 years old), raising the risk of housing instability after program completion. As one staff MacKillop member explained:

More young people are leaving at 16 into various programs that only last two, three years. But then the children are ending up often where they are approaching homelessness services at the end of these short-term programs if they are exited too early. (MAC_10)

Young people assessed as ineligible for semi-independent housing options, often due to behavioural concerns or being viewed as ‘too complex’, were more likely to be transitioned into private rentals subsidised by Better Futures, social housing or homelessness services. Family reunification was also a common transition pathway, though the extent to which this reflected young people’s wishes varied. Among the young people interviewed who were reunified, some expressed a clear desire to return to their families, while others described it as imposed by Child Protection. One young person reflected:

The department was dead set on me going back to my parents … I was seen by my child protection worker for a few weeks, but no services were offered. (YP_04)

Both MacKillop and cross-sector staff expressed concern that reunification was frequently driven by a lack of housing rather than a genuine assessment of young people’s needs or preferences. While they acknowledged that reunification can be a positive outcome when well supported, staff described it being used as a last resort and observed the practice contradiction:

Child Protection has spent five to however many years keeping them away from their family just for the moment they turn 18 to drop them off there again. So, what was the good of that? (MAC_05)

Transitions into homelessness services were frequently described as unacceptable, yet common. When housing could not be secured before a young person’s 18th birthday, young people were often referred to homelessness services:

When it comes to 17, 18 … we’re scrambling to make sure there’s an option for them and the risk of homelessness is so high … it is the majority to be honest. (MAC_18)

A cross-sector staff member echoed similar reflections:

Sometimes our kids exit into homelessness … I’m going to be honest [it’s] the majority … It’s not often that we hear about the success of our kids post-18 and having accommodation lined up, ready to go. (CS_04)

Although not considered an appropriate pathway, homelessness services were often the only available option.

Staff also described a sense of relief when young people were eligible for NDIS packages, because these offer additional housing options and ongoing support beyond age 18 years – supports that are lacking in other transition pathways. One staff member commented:

If we didn’t have NDIS there, we’d be sitting there going, well, let’s just hope for the best. (MAC_22)

Overall, while gradual supported transitions are widely viewed as best practice, they are not equitably accessed. Transition pathways are heavily influenced by systemic pressures, housing availability and narrow definitions of readiness, rather than by young people’s developmental needs or preferences. These findings are further explored in the following discussion of implications for practice.

Multiple transition planning documents contribute to variability in practice

In addition to inconsistencies in pathways and readiness decisions, the use of multiple documents contributes to variation in how transition planning is implemented.

Survey findings

Survey results highlighted that MacKillop staff use an average of six documents (SD = 2.82) to support transition planning. The most frequently used were the government-mandated transition plan (91.2%, n = 93), behaviour support plans (77.5%, n = 79) and safety plans (73.5%, n = 75). Document use differed across staff roles. Leadership and Development staff more often used government procedures (χ2(4, n = 102) = 11.26, p = 0.024) and assessment and progress records (χ2(4, n = 102) = 10.53, p = 0.032) while office-based staff were more likely to use ‘other’ documents (χ2(1, n = 101) = 6.982, p = 0.008), though respondents did not specify what was used.

Staff who reported using the transition plan as a guiding document were significantly more likely to conceptualise transition planning as including four key components (Table 8), suggesting that document use may influence staff understanding and implementation of transition planning. See Supplementary Material 9 for the number and proportion of documents used to guide transition planning across roles.

Table 8. Statistically significant associations between the use of the transition plan and four transition planning components

This table shows components of transition planning that were significantly more likely to be identified by staff who reported using the transition plan as a guiding document.

| Transition planning components |

Chi-square test |

|---|---|

| Develop a tailored Care and Transition Plan |

χ2(1) = 23.37, p = <0.001 |

| Regularly review and update plans |

χ2(1) = 12.82, p = 0.002 |

| Use plans to guide referrals and support |

χ2(1) = 6.60, p = 0.008 |

| Support young people to be active participants |

χ2(1) = 6.18, p = 0.042 |

Interview findings

Interview data confirmed that alongside formal documents, MacKillop and cross-sector staff frequently use informal tools to tailor planning to individual needs. Some MacKillop staff described developing team-specific checklists or using other organisations’ tools such as the Better Futures referral form (https://www.cpmanual.vic.gov.au/advice-and-protocols/tools-and-checklists/better-futures-referral-checklist), CREATE Foundation’s Go Your Own Way checklist and independent living skills assessments (https://createyourfuture.org.au/about-me/leaving-care/go-your-own-way-info-kit/). Cross-sector staff reported developing bespoke checklists to support transition planning for young people with disability and to identify the cultural support needs of multi-faith and multi-cultural young people. This multiplicity of tools may contribute to inconsistency in how transition planning is implemented.

Inconsistent use of the transition plan limits its impact on practice

Despite the mandated transition plan being the most frequently used document reported in the survey, interviews revealed inconsistent engagement with it in practice. Few MacKillop staff reported using the transition plan as ‘a live document’ that guided regular check-ins with young people and was referenced in care team meetings. One MacKillop staff member shared that it:

Informs me where we are up to with every single goal, and then I am checking in with that young person every week as to what goal we are up to and what we are doing that day. (MAC_01)

Staff more commonly described the plan as a static document developed primarily to meet compliance requirements. Although plans often inform care team agendas, they were seldom referenced during the meetings:

I don’t think anyone in the care team pulls it out and says, well, what does it say here? Like, how are we reviewing that? (MAC_18)

Plans were often updated retrospectively, drawing on discussions across care teams, house meetings and informal discussions with young people, which did not always lead to collaborative review or goal-tracking. As one MacKillop staff member described:

I have never pulled that out to say to someone, it is on here, so have we done it? Like, I am just doing it [the review]. (MAC_17)

Moreover, transition plans were not consistently shared with key staff involved in supporting young people’s transitions, including Targeted Care Package staff and house staff. As one MacKillop staff member noted,

I’ve never seen a transition plan; I just hear about the goals. (MAC_04)

Overall, these findings highlight inconsistent use of the transition plans. Together, these findings highlight that while the transition plan is widely used, it is often treated as a compliance task rather than a tool to support ongoing, collaborative planning. These findings are further explored in the following discussion of implications for practice.

Discussion

This study explored the implementation of transition planning in residential OOHC by examining who is involved in delivering planning, how it is conceptualised by young people and staff and how it is enacted in practice. Findings, discussed below, reveal variability in roles and responsibilities, conceptual understandings and planning processes across different demographic and organisational contexts.

Varied roles, responsibilities and transition pathways

Transition planning in residential care involves a complex network of professionals and service systems. Findings from this study highlight that decision-making power is typically concentrated among Child Protection practitioners who often have limited day-to-day engagement with young people. This reflects concerns in the literature about the absence of close, trusting relationships between young people and those responsible for making significant life decisions for them (Cameron-Mathiassen et al., 2022; Hiles et al., 2013; Hyde, 2018; Palmer et al., 2022; Venables et al., 2025).

The centralisation of decision making within Child Protection has significant implications for young people’s transition pathways. Transitions into semi-independent or independent housing commonly occur between the ages of 16 and 17 years and are framed as opportunities for young people to develop independent living skills while still under the legal care of Child Protection. While some staff viewed semi-independent housing as beneficial, in alignment with prior research, others described the timing was shaped more by system needs and service availability than by young people’s developmental readiness (Atkinson & Hyde, 2019; Gill & Oakley, 2018; Storø, 2017). Access to step-down housing and related supports was also described as inconsistent, particularly for young people with complex needs. In alignment with similar research, although semi-independent placements were frequently used as exit pathways, many young people experienced significant instability and homelessness after leaving care (Munro et al., 2022). These outcomes not only increase pressure on service systems, such as health, justice and homelessness, but also raise critical concerns about whether young people’s rights to stability and support are being upheld (Flatau et al., 2019). These findings contrast with growing evidence that extending care to age 21 years improves outcomes in housing, education, employment and wellbeing (Courtney et al., 2018; Mendes et al., 2025). Despite longstanding recognition that many young people exit care without sufficient readiness or support (Palmer et al., 2022; Stein, 2019; van Breda et al., 2020), early and poorly supported transitions remain common.

Staff perceptions of responsibility for transition planning varied across roles and settings. Survey data suggested that Residential Carers were viewed as having substantial responsibility for supporting transitions, yet interviews revealed their involvement was often limited, informal and unsupported. Despite their central developmental and relational role, they were frequently excluded from decision-making forums and did not consistently have access to planning documents. This role misalignment reflects broader implementation challenges related to unclear role definitions and the under-engagement of key frontline staff (Damschroder et al., 2022; Galvin et al., 2022; Stanton et al., 2022).

A similar disconnect was evident in young people’s experiences of planning. Although staff reported that young people were involved, young people described informal and indirect engagement, with many unaware of formal transition plans or stating they had never received a copy. When involvement did occur, it was more likely when plans were developed by Case Managers, indicating that engagement is shaped by individual worker practice rather than by consistent organisational processes, reinforcing existing evidence that young people’s voices are often underrepresented in decision making (Häggman-Laitila et al., 2018; McPherson et al., 2021). These challenges in participation and staff engagement are further exacerbated as young people near adulthood and planning responsibility shifts to services such as Better Futures and Targeted Care Package. While these programs are positive and designed to support young people beyond age 18 years, participants commonly described the handover as disruptive, particularly when new workers were unfamiliar to the young person. This disruption is compounded by the end of statutory orders, which signals the formal withdrawal of support from Child Protection and residential care staff. Rather than maintaining continuity, this shift reflects a broader policy emphasis on self-sufficiency over relational interdependence (Storø, 2018). Yet trust-based relationships are critical to effective transitions (Mendes & Purtell, 2021; Riise et al., 2024), and disruptions to these relationships can significantly undermine the planning process (Gopalan et al., 2019; Winters et al., 2020). Similar concerns were raised about coordination with external systems such as housing providers and the NDIS. While these systems are essential to supporting post-care pathways, their involvement is often characterised by unclear roles, limited information sharing and fragmented service delivery (Baidawi & Ball, 2023; Courtney et al., 2019; Palinkas et al., 2014).

To strengthen role clarity, relational continuity and coordination across the transition period, reforms should focus on:

- Clearly defining and communicating planning responsibilities across services and sectors;

- Formally recognising staff with trusted relationships, such as Residential Carers, and supporting their involvement through role-specific training, access to documentation and inclusion in planning processes;

- Ensuring young people receive, understand and actively shape their plan;

- Strengthening cross-sector collaboration to support smooth handovers and sustained support beyond statutory care; and

- Ensuring planning is responsive to young people’s developmental readiness rather than administrative timelines (Dinisman, 2014; Gabriel et al., 2021; Garcia-Alba et al., 2022).

Future research should examine the systemic and service-level conditions that enable or hinder collaboration and meaningful participation of both staff and young people.

Varied conceptualisation and practice

A lack of shared understanding about what transition planning involves among both staff and young people contributes to significant implementation challenges. MacKillop and cross-sector staff primarily conceptualised transition planning as a task-oriented process focused on service referrals, secure housing and supporting young people to develop life skills. Mandated components, such as referrals to Better Futures, were not consistently identified, and relational components were mentioned less often than other components, despite strong evidence supporting their importance (Armstrong-Heimsoth et al., 2021; McPherson et al., 2025; Milne et al., 2024; Sellers et al., 2020; Venables et al., 2025). This narrow conceptualisation was evident in the omission of programs such as HEALing Matters – an evidence-informed initiative designed to build independent living skills – which MacKillop staff are trained in but did not mention as part of transition planning (Cox et al., 2018). While the dominant conceptualisation of transition planning aligns with government policy (DFFH, 2012, 2024) and research on positive transitions (Alderson et al., 2023; Grage-Moore et al., 2025; O’Donnell et al., 2020b; Taylor et al., 2021), the omission of core elements points to the need for clearer framework. Without a shared definition of transition planning, staff may unknowingly overlook components that are essential to effective delivery (Damschroder et al., 2022; Proctor et al., 2011).

Young people also held a limited view of transition planning, reflecting limited awareness of the broader purpose of planning, a finding aligned with previous reports that young people in residential care are not adequately introduced to programs (Galvin et al., 2022). To be meaningful, transition planning must be grounded in young people’s goals, relationships and developmental readiness, rather than administrative requirements or system timelines (Appleton, 2024). Although based on a small sample, these insights underscore the need to ensure all young people are supported to participate in ways that are consistent, equitable and developmentally appropriate.

Compounding varied conceptualisations, documentation practices were also inconsistent. Staff used a mix of documents, including formal plans and bespoke checklists and bespoke tools, with frontline MacKillop staff less likely than leadership and cross-sector staff to report using government-endorsed templates. Despite planning being a mandated requirement (DFFH, 2012), few staff described using the transition plan as a live document. This limited use may explain why many young people were unaware of their plans and suggests that the transition plan in its current form does not meet the needs of either staff or young people (Damschroder et al., 2022).

Variation in how transition planning was conceptualised and delivered was also shaped by workforce and contextual factors. Staff in regional settings more often emphasised relational components, while those with lived experience of care described a broader range of planning elements. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander staff were more likely to identify cultural support and plan utilisation as central. These findings suggest that, in the absence of a shared framework, staff rely on their own knowledge, values and experience to guide practice, contributing to variability in delivery (Kor et al., 2021; Milne et al., 2024). Critically, when staff do not perceive components as integral to transition planning, they are unlikely to deliver these in practice (Damschroder et al., 2022; Proctor et al., 2011). While some flexibility is important to respond to the needs of diverse cohorts, well-defined programs are more likely to be implemented successfully when supported by structured frameworks (Maggin & Johnson, 2015; Powell et al., 2015). Furthermore, staff described adapting transition planning to better support specific cohorts, including Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander young people, young people with disability and those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. While this responsiveness is a strength, current planning frameworks may not provide adequate guidance for equitable implementation across all contexts (Barrera et al., 2017).

To strengthen the quality, consistency and responsiveness of transition planning, reforms should focus on:

- Developing a clearly articulated and structured conceptualisation of transition planning, supported by a unified framework that defines core components and adaptations;

- Providing culturally responsive, youth-friendly and neuro-affirming resources to support engagement and ensure consistency across diverse contexts;

- Delivering comprehensive training and guidance for all staff involved in planning to promote a shared understanding of expectations and responsibilities; and

- Redesigning planning tools so they are culturally and developmentally appropriate and meaningful for both staff and young people.

Future research is also needed to examine whether core components are being delivered as intended, perceived as useful and adapted appropriately, and to identify the systemic and service-level conditions that support or hinder meaningful participation.

Limitations

This study offers valuable insights into transition planning in residential care, but several limitations should be acknowledged. The sample was drawn from a single service provider, which may limit the generalisability to other settings. This limitation was mitigated, however, by including cross-sector participants who work with multiple residential care providers and care-experienced young people from different organisations. Similarly, as identified, Child Protection workers are essential to the transition planning process for young people in care, but they were unable to be recruited for this study. Future research should explore the perspectives of Child Protection staff and other residential care providers.

Care-experienced young people were underrepresented (n = 6 interviews, n = 2 surveys), driven by recruitment barriers, and the low survey response rate prevented quantitative data analysis. The sample was also not representative of the heterogeneous demographics of young people. During the study period, of the young people aged 15–17 years living in MacKillop’s residential care homes, 45.5% (n = 35) were male, 16.9% (n = 13) were from a multi-faith and multi-cultural background, 19.5% (n = 15) were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and 63.6% (n = 49) had diagnosed disability. While the transition plans represented all young people currently in care, the plans did not report cultural and linguistic diversity. Future research is required to understand how transition planning is implemented for different cohorts and to identify their unique needs and adaptations. To support greater representation, future studies should explore extended recruitment periods, deeper partnerships with youth-led organisations and more flexible or youth-driven participation methods to strengthen engagement.

There is also a risk of self-selection bias, where participants with more negative experiences of transition planning may have been more motivated to participate, potentially skewing findings toward critical perspectives. Finally, while this study identifies gaps between policy and practice, it does not systematically examine the underlying causes of those gaps. Future publications related to this program of research will report on the barriers and facilitators required to support system-wide improvements to transition planning practices.

Conclusions