Article type: Review

8 December 2025

Volume 47 Issue 2

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 7 April 2025

REVISED: 15 October 2025

ACCEPTED: 17 October 2025

Article type: Review

8 December 2025

Volume 47 Issue 2

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 7 April 2025

REVISED: 15 October 2025

ACCEPTED: 17 October 2025

![]() A literature review of therapeutic intervention with young survivors of violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect

A literature review of therapeutic intervention with young survivors of violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect

Affiliations

1 Cara Consultancy, Sydney, NSW 2140, Australia

Correspondence

* Mary Jo McVeigh

Contributions

Mary Jo McVeigh - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Mary Jo McVeigh1 *

Affiliations

1 Cara Consultancy, Sydney, NSW 2140, Australia

Correspondence

* Mary Jo McVeigh

CITATION: McVeigh, M. J. (2025). A literature review of therapeutic intervention with young survivors of violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect. Children Australia, 47(2), 3061. doi.org/10.61605/cha_3061

© 2025 McVeigh, M. J. This work is licensed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Abstract

With the advent of childhood studies, the nature of childhood as a sociological construct emerged. In the therapeutic context, central concepts such as ‘childhood’, ‘maltreatment’ and ‘therapy’ are written into the literature as taken-for-granted phenomena. Examination of these concepts is pivotal to any research on therapeutic intervention with children and young people who have experienced violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect. This allows the therapeutic field to examine how they are part of a child or young person’s context, how this context affects the construction of children and young people as they enter therapy, and how they, as therapists, are part of this contextual construction. A rapid review of the literature on therapeutic intervention was chosen because it provided a systematic mapping of the existing scholarship. A PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study design) strategy was developed and used to search seven databases. A thematic data analysis was conducted based on the research questions developed to explore the literature. Findings highlighted that a wide range of interventions is available to young survivors, but commentary on their effectiveness is dominated by adults and focused on individualised outcomes. The findings also highlighted a very narrow construction of young survivors’ identity within the therapeutic world. The key conclusion from this review is that there is a need to see young survivors as more than a sum of their experience of violence and abuse and deserving of a more credible seat at the epistemic table.

Implications

Information from clinical trials should be but one element in practitioners’ analytic discernment about how to proceed therapeutically.

Practitioners would benefit from critically reflecting on how they position young survivors in therapy and how this impacts young survivors’ healing.

Further research is needed to hear from both young survivors and practitioners how the construction of ‘childhood’ impacts service delivery.

Introduction

With the advent of childhood studies, the nature of childhood as a sociological construct emerged from the work of early scholars (Hendrick, 1997; James & James, 2004; Jenks, 2005; Prout, 2005) and was further expanded with contributions from feminist and post-colonial scholars (Balagopalan, 2019; Biwas, 2022; Burman, 2012; Cannella & Viruru, 2004; De Castro, 2020; Malone et al., 2020; Nieuwenhuys, 2013). Decolonising and feminist theories have shown that the very construct of childhood constricts children’s individuality and consigns them to ‘other’ – seen as different from adults. Cannella and Viruru (2004) highlighted that younger citizens are at risk of being subjected to the scientific gaze of adults when this othering occurs. Under this gaze, adult power is exercised over children through ‘institutionalized constructs that mentally and physically control’ (Cannella & Viruru, 2004: p. 85), placing them under social regulation (Rose, 1999). In addition, Hammersley (2017) expanded the notion of childhood as a construct to shift the focus on investigating the interactional contexts that exist in a child’s life and how children are constructed within these contexts.

In the therapeutic context, central concepts such as ‘childhood’, ‘maltreatment’ and ‘therapy’ are written into the literature as taken-for-granted phenomena. Examination of these concepts is pivotal to any research on therapeutic intervention with children and young people who have experienced violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect. This allows the therapeutic field to examine how they are part of a child or young person’s context, how this context affects the construction of children and young people as they enter therapy, and how they, as therapists, are part of this contextual construction. The significance of this cannot be underestimated. The Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS) (Haslam et al., 2023) unearthed that 62.2% of the population has experienced some form of maltreatment. The ACMS also reported that experiences of violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect correlated with a greater uptake of health services, which includes therapeutic services. Note: Goddard (1998: p. 28) wrote that ‘the use of a short and simple label’ in the child abuse field ‘allows us to communicate without the need to repeatedly define and re-define our terms. The disadvantage is that by using such an umbrella phrase, we inevitably lose something’. In order to allow me to communicate with the reader and not lose the painful reality of children and young people’s experiences, I will alternate between using short labels such as child abuse and maltreatment and writing out the full experiences as violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect. Moreover, to disrupt the mono-political positioning of the terms ‘children’ and ‘young people’, I will alternate between using these terms and the terms ‘young survivors’, ‘young citizens’, ‘participants’ and ‘clients’.

In this article, the definition of maltreatment is taken from the ACMS study. It includes physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, domestic violence and polyvictimisation. The percentage of the population in Australia experiencing some form of this maltreatment increased for the younger participants in the research cohort. These figures are a disturbing indication that violence against children in the familial context in Australia is not a historical issue of concern for only a few but a current major socio-political issue for younger citizens and their parents, carers and adult allies. Moreover, Meyer et al. (2023) reported that the foremost cause of death for young people in Australia is suicide. Their research found a strong connection between children and young people living with experiences of domestic and family violence and suicide. This is in comparison with the World Health Organization (WHO), which cited suicide as the fourth leading cause of death among young people and emerging adults worldwide (WHO, 2024). Multiple research projects over many years have highlighted that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are correlated with several poor health indicators, especially mental health (Sheffler et al., 2020). Therefore, it is of no surprise that the ACMS reported in their findings that accessing health services, mental health services and therapy has a direct positive correlation with enduring maltreatment.

Considering the extent of violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect, the positive correlation between service uptake and these violences, and the high rates of suicide among young citizens in Australia, it is crucial to consider the quality of service delivery that exists for young survivors. The need for effective intervention for their wellbeing, healing and survival is too significant to be left to a practice lottery of what’s on offer or to be overlooked as a subject of academic interest. Thankfully, this quality assurance aspect of service delivery is considered by practitioners and academics alike and is often debated through the concepts of evidence-based practice (EBP) or practice-based evidence (PBE). However, it is also crucial that interventions delivered as evidence-based are investigated to determine if any of the ‘institutionalized constructs’ that Cannella and Viruru (2004) alluded to are present. The intervention literature is a suitable source for this investigation, because practitioners are encouraged to stay informed about research and current academic debates, with peer-reviewed journals being regarded as the gold standard for disseminating knowledge. Therefore, this article will focus on reviewing the therapeutic literature contained within peer-reviewed journals.

Aim and research questions

Although, historically, little attention was given to the efficacy of treatment for children and young people who have experienced violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect (Briere, 1996), there has been an exponential growth in the focus on evidencing effectiveness since the 2000s (Wilson, 2012). Therefore, this article will focus on literature from the turn of the century. Peer-reviewed journals are replete with literature review articles that explore the available options for therapeutic interventions and those deemed effective. However, this article is interested in the contextual construction (Hammersley, 2017) of young survivors and their experiences within the academic debate on therapeutic effectiveness. Therefore, the search of the literature was based on five primary inquiries:

- Within this delivery service, how are young citizens constructed as ‘experiencers’ of ‘child maltreatment’?

- How is a young survivor’s response to violence, abuse and neglect constructed?

- What is the nature of the interventions on offer for young survivors?

- How is a young survivor’s experience of change or healing measured?

- What epistemic position is given to children and young people about their experiences of interventions?

Method

Arksey and O’Malley (2005) highlighted that a rapid review provides a methodical mapping of the existing scholarship, which suits the purpose of this article. To avoid bias and enhance the accuracy of literature retrieval (Cooper et al., 2018), a population–intervention–comparison–outcomes–study design (PICOS) framework (Table 1) (Richardson et al., 1995) was used to develop the search strategy.

Table 1. Population–intervention–comparison–outcomes–study design (PICOS) strategy for focusing the literature review

|

Area |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

Population/participants |

• Children and young people up to the age of 21 years who experienced some form of maltreatment. • The definition of maltreatment based on the most extensive research conducted in Australia, the ACMS (Haslam et al., 2023). |

|

Intervention |

• Therapeutic or counselling in either one of three forms: individual, family or group. |

|

Comparison group/counterfactual |

• All types of comparison groups. • No comparison groups. |

|

Outcomes |

• Specified as evidenced practice or research to establish evidence for effectiveness. |

|

Study design |

• Randomised controlled trials (RCTs). • Quasi-experimental designs (QEDs). • Qualitative studies. • Grey literature (reports, references from reviewed articles). |

Search and screening process

A comprehensive search strategy was devised after consulting with an expert librarian at a university library. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on the PICOS strategy and are contained in Table 2.

The search strategies identified keywords in titles, abstracts and subject headings permitted by the databases using search terms paired with the usual Boolean terms (Table 3).

The databases searched were chosen for their access to social work, psychology, psychiatry and counselling journals. The seven databases searched were CINAHL, Informit, PsycINFO, Social Services Abstracts, Sociology Source Ultimate, Scopus and Web of Science.

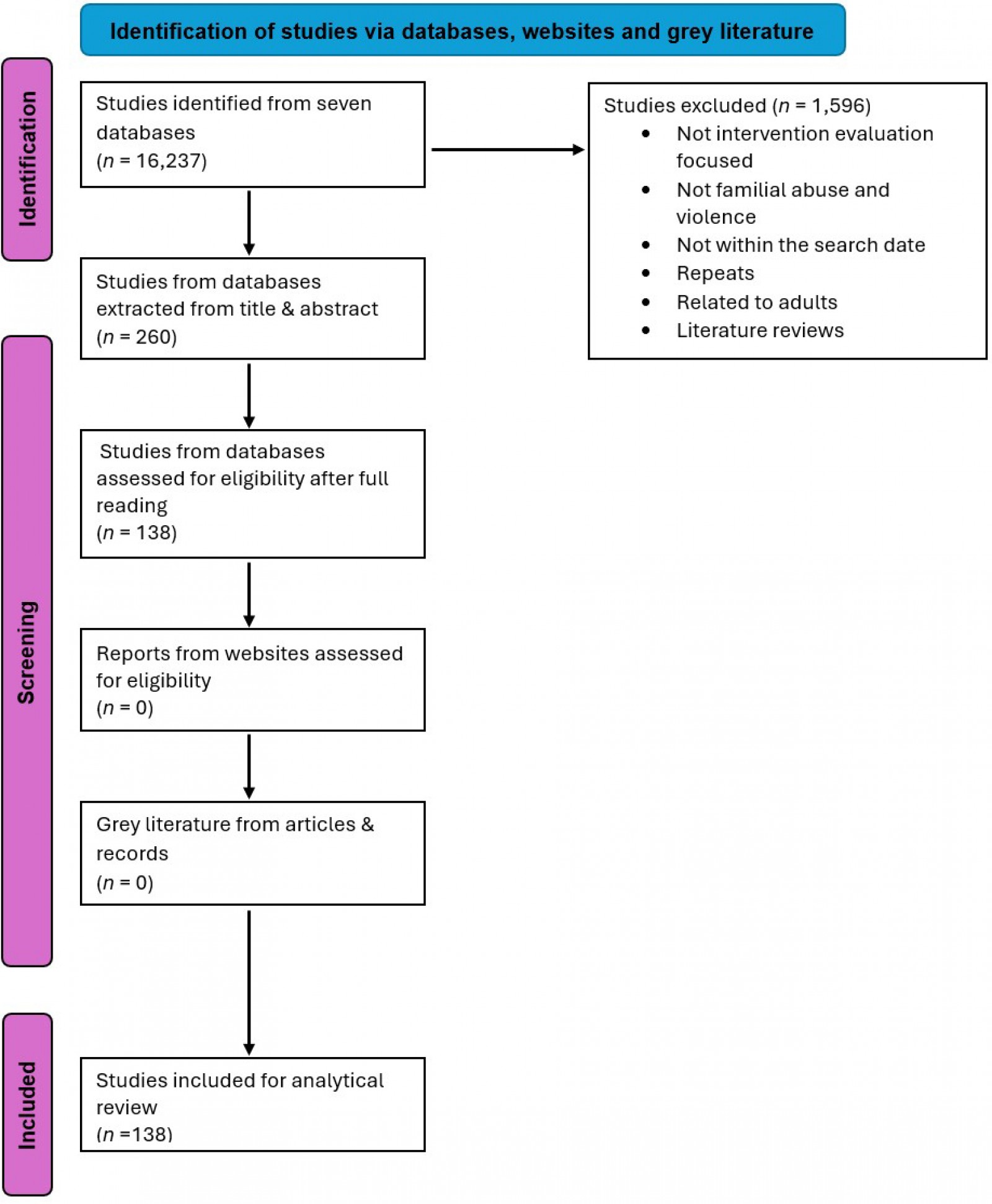

Figure 1 presents a PRISMA diagram (Page et al., 2021) of articles included in the review. After duplicates were excluded, 16,237 peer-reviewed articles obtained via database searches were examined. In total, 1596 articles were excluded at title and abstract screening, and 122 articles were excluded after the full texts were reviewed. The final number of articles for full review was 138.

Table 2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

|

Item |

Inclusion/exclusion factors |

|---|---|

|

Participants |

Set up to 21 years, despite the legal age of adulthood in Australia being 18 years of age, in some jurisdictions, statutory and non-government out-of-home care agencies maintain a role until the emerging adult turns 20 years. Adult survivors who had childhood experiences of maltreatment were excluded. The participants had experienced some form of maltreatment and undergone some form of therapeutic intervention. |

|

Experiences of violence, abuse, neglect |

Forms of trauma that were not maltreatment based within a familial context were excluded. |

|

Interventions |

Described as therapeutic and measured for effectiveness. The main focus of the therapy was on the child or young person and included individual, group, parent–child or family therapy. |

|

Studies |

Studies published in peer-reviewed journals between 2000 and 2024, and that were evaluative, were included. Studies that were excluded:

|

Table 3. Search terms used for the literature retrieval

|

# |

Search string |

|---|---|

|

1 |

child OR children OR ‘young people’ OR ‘young person’ OR ‘young adult’ OR ‘young m*n’ OR ‘young wom*n’ OR youth* OR teen* OR juvenile* OR Adolesc* OR minor OR minors |

|

2 |

‘sexual abuse’ OR ‘emotional abuse’ OR ‘sexual assault’ OR neglect OR ‘child abuse and neglect’ OR ‘sexual assault’ OR ‘sexual exploitation’ OR ‘child maltreatment’ OR ‘family violence’ OR ‘ physical abuse’ OR ‘domestic violence’. |

|

3 |

treatment* OR counselling OR therap* OR psychotherapy OR intervention OR counseling OR therapy |

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram

Data extraction

A template was developed to extract information from each article. The template aimed to minimise bias and increase the targeted nature of information retrieval. It was saved in an Excel spreadsheet under the following specific fields: authors and date; location of study; journal; professional background; model; abuse and violence; diagnosis; description of effectiveness; reasons for effectiveness; measures; inclusion/exclusion criteria; and contribution from children and young people. Where information for a specific field was not available in the article, the field was recorded as ‘NS’ (not specified). Where inclusion/exclusion criteria were not given, they were recorded as NG. The spreadsheet is available in Supplementary Material 1.

Results

The reviewed articles were skewed to articles written in English. However, the search yielded articles from Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Germany, India, Éire Ireland, Iran, Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, Pakistan, the Philippines, South Africa, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States and Zambia. Results showed that the USA dominated the debate within the scholarly landscape: 53.6% of the 138 articles reviewed were located in the USA. The nearest percentage to this was the UK and Canada, which dropped dramatically to 7.9%. Australia represented 2.9% of the articles reviewed and the remaining countries accounted for representation between 3.6% and 0.7%. While considering global trends in a local context is always important, these findings are particularly relevant for decision makers who determine the suitability of interventions in Australia’s First Nations and diverse cultural contexts. Moreover, there was no specific discussion in the literature on whether the interventions were specifically designed for remote, rural or urban contexts of children’s lives.

The affiliations of the article authors were heavily weighted toward contributions from academics, either as sole authors or in collaboration with external research departments or agencies. Contributions from practitioners accounted for 5.3% of articles, and no articles were identified as having been written or co-authored by children and young people or individuals with lived experiences of maltreatment. This may reflect the fact that peer-reviewed journals are the main conduit for disseminating research and have traditionally been the domain of academics. To explore these published findings, the remaining parts of this section will address the results under the five primary inquiries used to explore the literature.

How are young citizens constructed in the literature as ‘experiencers’ of the violent and abusive actions of adult family members?

The literature reviewed discussed the experience of young citizens who endured and survived all forms of violent and abusive actions within the family context under distinct categories: physical abuse; sexual abuse/assault; domestic and family violence; emotional abuse; and neglect. The word ‘violence’ was only used in connection with domestic violence; the other forms of violence (i.e. sexualised, emotional and physical violence), were described using the word ‘abuse’. Despite social work and psychology professionals stipulating the claim that they work with the whole identity of a person, the oppressive impact on gender, culture, spirituality, sexual preference, age, ability or death loss was not explored in the literature, nor did any articles discuss assets that young citizens pulled upon when revisiting and healing from violence and abuse.

The therapeutic literature describes survivors’ identities in commonly accepted developmental terms –adolescent, child, young person and youth. Table 4 highlights that most articles (n =88) placed the person’s developmental status first, followed by the violence/abuse category, hence dignifying the person’s identity from the experience. The language used to delineate the person from the violence/abuse was embedded in terms such as ‘affected by’, ‘endured’, ‘experienced’, ‘exposed to’, ‘have been’, ‘history of’, ‘identified as’, ‘impacted by’, ‘suffered’, ‘survivors of’ and ‘witnessed’. The terminology ‘exposed to’ was utilised the most in connection to domestic and family violence (n = 14) and ‘experienced’ when referring to child abuse and neglect (n = 12). Domestic violence was also the only form of violence that survivors were said to have witnessed (n = 4).

In articles where the form of violence was placed within the person’s identity, the descriptions included ‘abused or neglected youth’(n = 2), ‘at-risk youths’ (n = 1), ‘child sexual abuse survivors’ (n = 1), ‘maltreated children’ (n = 5), ‘sexually abused children/girls/adolescents’, (n = 14), ‘traumatised children’ (n = 15), ‘trauma-exposed children’ (n = 5), ‘victims’ (n = 4), ‘victim-survivors’ (n = 1) and ‘vulnerable children’ (n = 1). The trauma descriptor was utilised in many articles (n = 42), either as the descriptors of the person, (i.e. traumatised child), or to describe the experience of the violent and abusive actions and behaviours of others (e.g. youth with complex trauma or trauma sequelae in children). While it was heartening to see 88 articles honouring people’s personhood separate from the violent and abusive actions and behaviours of others, it was also noteworthy that a high number (n = 50) still merged identity and experience. On the other end of this continuum were articles that distanced the reality of violence by describing the experience as ‘witnessed’. Thankfully, the term ‘witnessed’ was only used in four articles. However, all these articles were written about domestic and family violence.

The language of surviving the violent and abusive actions and behaviours of others was largely missing from the literature, with only three out of 138 articles using this description of young people either solely (n = 2) or in combination with the word victim (n = 1). Overall, the participants in the research were described only in terms of their developmental age rather than their citizenship and the acts of violence. Political and purposeful terminology of, for example, ‘oppressed by’, ‘discriminated against’, ‘repressed’, that placed the violence and abuse in the responsibility of the adults, was missing.

Table 4. Construction of young citizens impacted by violence, abuse and neglect

|

Description |

Number of articles |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Abuse/violence category stated first |

||

|

Abused or neglected children/youth |

2 |

|

|

At risk youths |

1 |

|

|

Child sexual abuse survivors |

1 |

|

|

Maltreated children |

5 |

|

|

Sexually abused children/girls/adolescents |

14 |

|

|

Vulnerable children |

1 |

|

|

Affected by |

||

|

Children who have been affected by abuse |

1 |

|

|

Children and young people affected by domestic violence and abuse/sexual abuse |

2 |

|

|

Children |

||

|

Children in care because of abuse |

1 |

|

|

Endured |

||

|

Children who endured complex trauma |

1 |

|

|

Children who endured abuse and neglect |

1 |

|

|

Experienced |

||

|

Children who experienced abusive relationships, particularly domestic violence |

1 |

|

|

Children/young people who experienced abuse and neglect |

12 |

|

|

Children who experienced trauma |

5 |

|

|

Children who experienced domestic violence |

5 |

|

|

Exposed to |

||

|

Children exposed to interpersonal violence |

1 |

|

|

Children/ pre schoolers/young people/youth exposed to domestic violence/intimate partner violence/family violence/intra family violence |

14 |

|

|

Children/exposed to abuse |

3 |

|

|

Children/exposed to trauma |

2 |

|

|

Have been |

||

|

Children who had been abused |

3 |

|

|

Children and young people who have been sexually abused |

6 |

|

|

Child victims of violence/ abuse |

3 |

|

|

Children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms |

1 |

|

|

History of |

||

|

Adolescent/children with history of abuse |

2 |

|

|

Children with history of trauma/trauma exposure/sexual abuse |

8 |

|

|

Identified as |

||

|

Children who are identified as maltreated |

2 |

|

|

Impacted by |

||

|

Children impacted by trauma |

1 |

|

|

Youth impacted by sexual abuse |

1 |

|

|

Suffered |

||

|

Adolescent/children who suffered trauma |

2 |

|

|

Survivor |

||

|

Adolescent survivors of child sexual abuse |

2 |

|

|

Victims/survivors |

1 |

|

|

Witnessed |

||

|

Children who witnessed domestic violence |

4 |

|

|

Trauma focused |

||

|

Adolescent/children who suffered trauma |

2 |

|

|

Children who endured complex trauma |

1 |

|

|

Children who experienced trauma |

5 |

|

|

Children/exposed to trauma/ |

2 |

|

|

Children impacted by trauma |

1 |

|

|

Children with history of trauma/trauma exposure/sexual abuse |

8 |

|

|

Children traumatised by family violence |

1 |

|

|

Traumatised children/adolescent/girls/youth |

15 |

|

|

Trauma exposed children/ adolescent |

5 |

|

|

Trauma sequelae in children |

1 |

|

|

Youth with complex trauma |

1 |

|

|

Victim |

||

|

Victims/child victims of abuse |

4 |

|

|

Victims/survivors |

1 |

|

How is a young survivor’s response to violence, abuse and neglect constructed?

As evidenced by the findings of this literature search, the language used to describe the impact of violence, abuse and neglect was mainly situated in a diagnostic context (Table 5). The most predominant descriptor utilised was that of trauma, with 65 articles describing it as complex trauma (n = 2), post-traumatic stress (n = 10), PTSD (n = 42) and trauma symptoms (n = 11). After trauma descriptors, behaviours either specific (e.g. self-harming), or as a disorder (e.g. emotional behavioural disorder), were used widely (n = 21). The remaining articles moved between descriptions of non-specified mental health labels (e.g. psychotic), to specific diagnostic categories (e.g. depression/depressive disorders (n = 9), anxiety/anxiety disorder (n = 5) and ADHD (n = 4), conduct disorder (n = 2)). Some articles included the physical aspect of the aftermath of violence for young survivors (e.g. struggles with sleep, eating and toileting).

Table 5. The language to describe the impact of violence, abuse and neglect

|

Descriptor |

Number of articles |

|---|---|

|

Adjustment disorder |

2 |

|

Anxiety |

5 |

|

Anger/violence |

1 |

|

Attachment disorder |

2 |

|

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) |

4 |

|

Autism/ASD |

1 |

|

Behavioural problems |

7 |

|

Bipolar disorder (BD) |

1 |

|

Clinically symptomatic |

1 |

|

Complex psychiatric problems |

1 |

|

Complex trauma (CT) |

2 |

|

Conduct disorder (CD) |

3 |

|

Depression/depressive disorder |

9 |

|

Dissociative symptoms |

1 |

|

Disruptive disorder |

1 |

|

Dysthymic disorder |

1 |

|

Emotional/behavioural disorder/problems |

2 |

|

Eating problems |

1 |

|

Encopresis |

2 |

|

Enuresis |

1 |

|

Hoarding |

1 |

|

Learning problems |

1 |

|

Mental health symptoms |

1 |

|

Mood disorder |

1 |

|

Oppositional defiance disorder (ODD) |

1 |

|

Psychological disorder |

1 |

|

Psychological distress |

2 |

|

Psychopathology (abnormal, severe) |

2 |

|

Psychotic thoughts/behaviours |

1 |

|

Post trauma stress (PTS) |

10 |

|

Post trauma stress disorder (PTSD) |

42 |

|

Reactive attachment disorder |

1 |

|

Recidivism |

1 |

|

Relationship problems |

2 |

|

Risk taking |

1 |

|

Self-injurious behaviour |

1 |

|

Sexual anxiety |

1 |

|

Sexual behaviour problems |

2 |

|

Sleep disorder/problems |

2 |

|

Substance abuse |

1 |

|

Suicidal/suicidal ideation |

2 |

|

Trauma symptoms |

11 |

|

None given |

54 |

What is the nature of the interventions on offer for young survivors?

The interventions evaluated in the literature varied in the creativity of the approach. Where specified, they fell into three main categories: individual (n = 70); group work (n = 42); or family or parent–child (n = 20). However, when the modality was named Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) in its pure or combined form (e.g. Trauma-focused CBT, Game-based CBT), it appeared in literature as the most researched form of therapy (n = 30). Expressive and arts-based interventions, including drawing, painting, craft, sewing and play, were the subject of 14 articles, primarily employed in group work settings. Performing arts activities were utilised in three articles: dance (n = 1); poetry (n = 1); and psychodrama (n = 1). At the same time, sports-based intervention was evaluated in only one article. Engagement with nature and the living environment was explored in 10 articles, including camps (n = 2), animal-assisted therapies (n = 7) and gardening (n = 1). The use of mindfulness or activities associated with this philosophical and spiritual tradition was the focus of three articles: two on mindfulness and one on yoga. The language of resilience or strengths-based practice was utilised in four articles to describe the intervention. A small number of articles evaluating various forms of expressive and performance arts and activities, and resilience or strengths-based practice, places them at the bottom of the evidence ‘league’. Moreover, only one article discussed a specific form of cultural practice (Becker et al., 2008) and two articles emphasised cultural/ancestral background as an essential aspect of the intervention (McVeigh & Oliveri, 2019; Moss & Lee, 2019). Only three articles incorporated the concept of spirituality into their interventions (Coholic et al., 2009a, 2009b; McVeigh & Oliveri 2019; Moss & Lee, 2019). Only one article employed a more political context to frame the intervention (Callaghan et al., 2018). Callaghan et al. (2018)described the group’s purpose as empowerment. It is interesting to note that the authors did not use mental health or behavioral language to describe the participants’ responses to the violence and abuse they suffered, nor did they use a standardised psychological or psychiatric tool to measure the effectiveness of the intervention.

How is a young survivor’s experience of change or healing measured?

When the intervention’s effectiveness was discussed, it was mainly described in terms of either improvement in mental health symptoms (46 articles) or behavioral changes (26 articles). The remaining changes were not improvements in relationships (n = 8) or social and personal skills (n = 10), and the article (Beetham et al., 2019) that specifically looked at resiliency programs showed an increase in resilient indicators as defined by the intervention.

Professionals who evaluate and write on therapeutic interventions use clinical standardised measures as their evaluation tool. Table 6 lists 94 distinct measures used in the reviewed studies. These measures were used 242 times across the studies. Trauma measures were used most frequently. The following most extensive measures used were symptom measures, which were used 56 times, followed by behavioural measures, which were used 55 times. Young citizens’ experiences of violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect are, therefore, prescribed and measured as clinically constructed phenomena.

Table 6. Tools utilised when determining therapeutic effectiveness

|

Behavioural measures |

|---|

|

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) |

|

Child sexual behaviour inventory (CSBI) |

|

Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI) |

|

Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC) |

|

Assessment Checklist for Children (ACC) |

|

Abbreviated Dysregulation Index (ADI) |

|

Youth Self Report Form (YSR) |

|

Child and Adolescent TRAG (CA-TRAG) |

|

Symptoms measures |

|

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) |

|

The revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) |

|

State-Trait anxiety inventory for children (STAIC) |

|

Symptoms Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90-R) |

|

Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths–Mental Health (CANS Mental Health) |

|

Symptoms and Functioning Severity Scale (SFSS) |

|

CAFAS – Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale |

|

Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) |

|

Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Disorders (SCARED) |

|

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children (ADIS) |

|

The Multidimensional Anxiety scale for children (MASC) |

|

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) |

|

The Short Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (SCESD) |

|

Youth Outcome Questionnaire (YOQ) – symptom measure |

|

Paediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC) |

|

The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS) |

|

Child Dissociation Checklist (CDC-3) |

|

Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale (A-DES) |

|

The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self Report (QIDS-SR) |

|

Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation (FASM) |

|

Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-Severity) for psychopathology |

|

Trauma measures |

|

Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children (TSCYC) |

|

K-SADS-PL |

|

General Trauma Information Form |

|

Urban Trauma Index (UTI) |

|

Trauma Symptom Checklist (TSCC) & Trauma Symptom Checklist Alternate Version (TSCC-A) |

|

UCLA PTSD-RI |

|

Young Child PTSD Checklist (YCPC) |

|

Child Report of Post-Traumatic Symptoms (CROPS) |

|

Lifetime Incidence of Traumatic Events, Student Forms (LITE-S) |

|

Children’s impact of traumatic events-revised (CITES-R) |

|

Children’s Post-traumatic Stress Reaction Index (The CPTS-RI) |

|

Adolescent Trauma History Checklist & Interview (THCI) |

|

PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL-C) |

|

Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ) |

|

Traumatic Events Screening Inventory – Child version (TESI-C) |

|

Feelings measures |

|

Children’s Hope Scale (CHS) |

|

Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) |

|

Children’s fears related to victimisation (CFRV) |

|

Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) |

|

Children’s Loneliness Questionnaire (CLQ) |

|

Hopelessness Scale (HS) |

|

The Paediatric Emotional Distress Scale (PEDS) |

|

Fear Thermometer (FT) |

|

The Shame Questionnaire (SQ) |

|

Children’s Alexithymia Measure (CAM) |

|

Self-Other Four Immeasurables Scale (SOFI) |

|

Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) |

|

Inventory of Callous and Unemotional Traits – Youth Self Report (ICU-Y) |

|

The Short Mood Feeling Questionnaire (SMFQ) |

|

Life satisfaction Survey (LSS) |

|

The Children’s Emotion Management Scales (CEMS) |

|

The Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC) |

|

Relationship measures |

|

Randolph Attachment Disorder Questionnaire (RADQ) |

|

Multidimensional Social Support Scale (MDSS) |

|

Security Scale (SS): Attachment scale |

|

Family Empowerment Scale (FES) |

|

Family Assessment Device (FAD) |

|

Child Ecology Check In (CECI) |

|

Social Network Map (SNM) |

|

The Tool Task (TT) |

|

Manchester Child Attachment Story Task (MCAST) |

|

Perception measures |

|

Piers–Harris 2 Self-Concept Scale for Children (SCS) |

|

Child Perceived Self Control (CPSC) |

|

Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC) |

|

Children’s Knowledge of Abuse Questionnaire (C-KAQ) |

|

Personal Safety Questionnaire (PSQ) |

|

Impact of Events Scale (IES) |

|

Harter’s Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children (PSPCSAYP) |

|

What If Situations Test (WIST) |

|

Somatic Awareness Measure (SAM) |

|

Children’s Attributions and Perception Scale (CAPS) |

|

Self-esteem measure (SEM) |

|

Strengths/Resilience measures |

|

Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths (CANS) |

|

Resiliency Scales for Children and Adolescents (RSCA) |

|

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) |

|

Miscellaneous measures |

|

CYRM-28 |

|

Child Exposure to Domestic Violence (CEDV) |

|

Movement Indicator Checklist for Sexually Abused Children |

|

Intervention measures |

|

Children’s Outcome Rating Scale, (CORS) |

|

Children’s Group Session Rating Scale, (CGSRS) |

|

Multidimensional Adolescent Assessment Scale (MAAS) |

|

The Therapy Process Observational Coding System for Child Psychotherapy Alliance Scale (TPOCS–A) |

|

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) |

|

Treatment Evaluation Inventory (TEI) |

|

The Telehealth Satisfaction Questionnaire (TSQ) |

What epistemic position is given to children and young people about their experiences of interventions?

The paucity of contributions from young survivors regarding the nature of therapeutic intervention was evident in the discovery of only 21 articles that included direct views from young citizens (Table 7). This varied in depth from one or two lines to a substantial inclusion of young people’s dialogue. When young survivors described their experiences of intervention and the components of therapeutic effectiveness, five broad themes emerged: therapeutic activities; discussing issues; therapeutic relationships; improved relationships; and the gains they achieved as a result of attending therapy.

Therapeutic activities were not described in the tenets of any specific model, but rather as the activities in which children and young people engaged during the intervention (n = 7). They prioritised three forms: creative; enjoyable; and skill-gaining. The most significant value given to these activities was having fun. While the importance of activities was a stand-alone benefit of therapy, children and young people also spoke about the activities they engaged in as a necessary part of the therapeutic process that assisted them in relating to the therapists and others, expressing painful and emotionally charged experiences and enhancing skills attainment.

In six of the reviewed articles, some young survivors spoke directly about the benefit of talking about the abuse or violence. However, for some, it is a confronting and frightening experience (Carroll, 2002; Dittmann & Jensen, 2014; McManus et al., 2013). In those situations, the young survivors emphasised the importance of the therapists, which echoed the significance of the therapist that was highlighted in other articles. Several aspects of the therapist’s stance were described in the literature, such as the therapist being trustworthy (Cater, 2014), safe (Dittmann & Jensen, 2014; Dunlop & Tsantefski, 2018), believing them (Nelson-Gardell, 2001), giving them information (Dittman & Jensen, 2014), involving them in decision making (Cater, 2014), being trusted (Cater, 2014), respected (Gilligan, 2016), and cared about (Jessiman et al., 2017).

The issue of relationships emerged in the feedback from young people regarding therapy. They valued their relationships with therapists (n = 4), including therapy animals (n = 2), and reported improvements in relationships both within and outside the therapeutic context (n = 16). Indeed, the relational elements of engaging in therapeutic intervention were second to the importance of gains mentioned by the participants in the reviewed studies.

Young survivors valued the gains made as a result of attending therapy in all the articles reviewed. These gains were described in terms of increased social and emotional skills, the ability to relax, self-esteem, self-awareness and improved relationships.

Table 7. Young people’s views about the nature of effective therapeutic intervention

|

Author |

Modality |

Feedback |

|---|---|---|

|

Resilience-based group work |

Fun; Importance of relationships; Having choice; Importance of considering aspects of their lives apart from experiences of violence |

|

|

Equine-assisted therapy (EAT) |

Increase in confidence-building and self-esteem; Increased self-efficacy; Increased empathy and relationship building; Provided with positive opportunities |

|

|

Empowerment-focused group work |

Increased ability to talk about the abuse |

|

|

Individual psychotherapy |

Increased ability to talk about the abuse: Improvement in relationships |

|

|

Play therapy |

Aspects of the therapist’s demeanour was helpful; Being given choices; Being given information; Therapeutic exercises; Fun and free play |

|

|

Community-based group work |

Increased ability to talk about the abuse |

|

|

Art therapy |

Increased self-esteem; Increased self-awareness; Increased connection to their feelings; Gaining new coping skills; Increased ability to relax |

|

|

Art and mindfulness |

Improved emotion regulation, mood, coping/social skills, confidence and self-esteem, empathy, and ability to pay attention and focus |

|

|

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (TF-CBT) |

Importance of ‘nice’ and ‘safe’ therapist; importance of talking to a therapist because of their expertise; being understood; therapist commitment to confidentiality; mixed reaction to having to recount the traumatic event; Reduction in symptoms: Improved view of themselves |

|

|

EAT |

Sense of emotional and physical safety; fun; Kind and compassionate staff; Friendship; Improvements in interpersonal skills; Overcoming fear |

|

|

TF-CBT |

Increased self-esteem; Increased self-awareness; Gaining new coping skills; Improvement in relationships |

|

|

Empowerment-focused group work |

Increased self-expression and awareness; Releasing the participants from the power of the offenders; Increased self esteem |

|

|

Individual psychotherapy |

Importance of a mutual understanding of therapeutic goals; Play; Link between child viewing the therapist positively and working on therapeutic tasks |

|

|

No modality specified |

Having fun; More confident and outgoing; Improvement in social connections and relationships; Reduction in physical symptoms; Relief that it was not their fault; Less anxious and stressed; Having choices |

|

|

Mother–child group work |

Improved relationships with mums; Fun and creative activities; Some children found sharing experiences and feelings helpful, while others found it upsetting: Some children made friends, some remained shy: Helped them improve their behaviour |

|

|

Resilience-based art and expressive therapy group work |

Increased confidence in relationship building and social skills attainment; Increase in self-efficacy; New skills: Increased emotional regulation; Increased connection to culture. |

|

|

Education/support group |

Increased confidence; Increased social skills |

|

|

No modality specified |

Increased ability to talk about the abuse; Increased connection to their feelings |

|

|

CBT in parent–child therapy |

Improved parenting; Improved relationship with parents; Achieved new life skills |

|

|

Expressive arts therapy |

Reduced sense of isolation; Improved self-expression and awareness; Increased self-esteem: Improvement in relationships; Personal growth |

|

|

Trauma-informed art and play therapy |

Improved self-expression; Usefulness of art to express feelings; Fun; Improvement in behavioral difficulties; Improvement in relationship with mothers |

Discussion

The tenets of social constructionism apply to all social phenomena and are reflected in actors’ performances of self, their actions and relationships. Children and young people are no different; childhood studies are replete with scholarly debate on childhood as a constructed phenomenon and how it plays out in the lives of young citizens. This article aimed to explore the nuances of a constructionist view of young citizens who endured violence, abuse and neglect within the therapeutic world, as evidenced in the literature. The review uncovered a myriad of interventions that highlight the commitment from both practice and academia to provide this accountability and efficacy of intervention. Without question, engaging with children and young people to alleviate distress/anguish/suffering resulting from maltreatment is a moral and socio-political imperative. Any effort to ensure professional accountability and effectiveness when intervening in the lives of children and young people who have endured violence, abuse and neglect should be applauded and embraced. However, what was also evident was that, overwhelmingly, regardless of the interventions utilised by therapists, the child or young person was primarily the focus of change. This focus on children as the site of change is despite Ungar’s (2017: p. 1285) contention that when looking for improvement in a child’s life, ‘very few of the changes that occur, however, can be attributed exclusively to individual etiological factors’.

In the health and welfare fields that engage young citizens, the term evidence-based practice (EBP) is commonly used to describe the pursuit of intervention efficacy. Agencies often encourage and sometimes stipulate the use of specific interventions. Funding bodies often require agencies to employ evidenced interventions. Markedly, researching, writing about, and deciding on what counts as evidence-based practices are not neutral issues. Indeed, Miller et al. (2015: p. 450) believed institutions established as the primary arbiters or evidenced practices ‘are reshaping clinical practice, becoming key drivers of how therapists work and are paid’. Because peer-reviewed journals are considered to play a vital role in directing practice (Zoccali & Mallamaci, 2023), it is essential to consider who holds the dominant position in disseminating knowledge that will influence practitioners and, indeed, funding bodies. As Coates and Wade (2007) reminded us:

Professionals, academics, celebrities, corporate leaders, government officials, candidates for political office, and men are typically more able than others to circulate their own views and influence the extent to which competing views are aired. (p. 511)

Upon examining the therapeutic literature, it became evident that adult professionals were more prevalent than young survivors in disseminating their views on therapeutic interventions. The commitment to ensuring quality service delivery to young citizens who have survived maltreatment is not contested here; that the vast majority of articles did not privilege young survivors as ‘their own example in the struggle for their redemption’ (Freire, 1970: p. 36) remains a significant finding. There was no specific discussion in the literature on the community context of young people’s lives and whether the interventions were specifically designed for a remote, rural or urban context. Moreover, there was no discussion of intersectional issues related to their identity, including gender, culture, class, ability or sexual orientation, existing in their lives, let alone being an asset to their healing and, hence, a necessary component of therapy. This exclusion reduces young citizens to a wafer-thin version of themselves, that of the ‘abused child’. Despite many articles (Table 4) scripting the young person’s identity as separate from the experience of the violence and abuse, if the depth of young citizen’s personhood is not fundamental to therapeutic intervention, despite writing them into the academic discourse as ‘the abused child’ or ‘the child who has experienced abuse’, we are not honouring the profundity of their existence. Neither is the impact of their distress/anguish/suffering nor their acts of survivance treated with the complexity that they deserve. Survivance is a term coined by the Native American activist and academic Vizenor. Vizenor (2008: p. 11) saw survivance as ‘an active resistance and repudiation of dominance, obtrusive themes of tragedy, nihilism and victimry’. A survivance framework shifts the lens of interpretation from regarding young survivors’ reactions as clinical symptoms or reactive behavioural effects to actions as political acts of survival and growth.

That young survivor’s distress/anguish/suffering is constructed mainly in the public transcript of social work, psychology, psychiatry and counselling professions as mental illness was evident in the cascade of the terminology that is used to describe them in the literature. O’Connor and McNicholas (2020) found that children, young people and their families experienced relief when they received a diagnosis, because it provided a sense of stability and an explanation for the distress they were feeling. They also felt a myriad of loss, stigmatisation and self-blaming feelings. Moreover, O’Connor and McNicholas (2020) found that a shift in diagnosis meant an entirely new therapeutic plan and resulting confusion for young survivors. It is easy to see how, in this mental health discourse, children/young people are psychiatrised (LeFrançois & Coppock, 2014). In this psychiatric context, assigned clinical conditions are created, necessitating clinical interventions that, in turn, require clinical measures to assess the effectiveness of these interventions in terms of clinical outcomes, thereby addressing these conditions. Within this diagnostic discourse, there was no acknowledgment of socio-political sources of the violent and neglectful acts. Huggard and O’Connor’s (2025: p. 12) research concluded that ‘the sociopolitical determinants of mental illness may promote more tolerant attitudes towards people with mental illness’. These findings by Huggard and O’Connor (2025) not only have implications for a public shift in attitudes but also raise the question of whether there would be a shift in intervention modalities if the socio-political gained more space in exploring intervention. Would young survivors then be constructed less as asymptotic chess pieces moving across a diagnostic board and more as vibrant beings responding to, surviving and moving forward with life in the face of the different forms of violence they endure?

The overwhelmingly predominant one of these clinical constructs in the literature was that of trauma. Of the articles that named a specific psychiatric diagnostic label (Table 5), 77.4% used the trauma descriptor. A trauma framework can serve children and young people when it locates the sources of their suffering/anguish/distress in adult actions and the socio-political context of their lives, not as an individualist psychiatric diagnostic label predominantly does, in a taint that lies within them. A trauma framework also politicises the magnitude of abuse and violence against young citizens, as exemplified in the ACMS (Haslam et al., 2023), and invites practice, academic and political attention to avoid the ravages of short and long-term effects, as evidenced in the ACES research (Sheffler et al., 2020). However, Tseris’s analysis of trauma intervention for adult survivors highlights that it has become ‘preoccupied with medically oriented issues concerning diagnosis and standardized treatment’ (Tseris, 2013: p. 156). This preoccupation in the literature thwarted the opportunity to hear from ‘psychiatrised’ children and young people and to value their activist voice, which got lost in the noise of diagnosis, measurements and interventions. Scott (1990) reminded us of the importance of the hidden transcripts for the survival of people who have been oppressed and how bringing these transcripts into the public space can ‘restore a sense of self-respect and personhood’ (p. 210). Therapeutic interventions have the potential to become public spaces to restore young citizen’s self-respect and personhood. However, to do so, they must shift the focus of the outcome from purely curative concerns to political and transformative/restorative ones, where the children and young people are epistemically privileged as the authors of their healing narratives.

It was also evident that the construction of the ‘psychiatrised’ child or young person was based on the psychological self, physical self, emotional self: not the spiritual self. This was evident in the psychological language of the effects of violence and abuse that traumatised children and needed psychological intervention to cure symptoms or change behaviours. The language of soul violence towards young citizens was absent. I define soul violence as that form of violence that is inherent within others and can permeate into the sense of self and one’s existence. Eaude (2023: p. 23) argued that ‘children’s spirituality should be more prepared to address difficult and controversial issues and be bolder and more radical’. It would appear that in the difficult issue of violence against children and young people, and how to provide therapeutic intervention, the field needs to be bolder and radical.

Limitations

The limitation of this review is that it only accessed articles written in English, thereby excluding more culturally diverse sources of literature. Despite contacting several organisations with an expression of interest for any young people who may want to co-author, none were forthcoming. Therefore, the examination and analysis of the literature were conducted by a single reviewer. However, the bias of the sole reviewer was minimised by ensuring adherence to the protocol of a scientific literature retrieval procedure and the use of themes that captured the research questions, which were then recorded in a pre-set spreadsheet and thematically analysed.

Conclusion

The discussion of the findings of this literature review cannot be closed without circling back to the fact that the emphasis of this article was on literature in peer-reviewed journals that form part of the ‘evidence’ in the EBP debate. Perry and Frampton (2019: p. 366) reminded us not to rely solely on the results of clinical trials that do not occur within the daily work of agencies, because this can lead to mixing up ‘statistical significance with clinical significance’. Information from clinical trials should be but one element in practitioners’ analytic discernment about how to proceed therapeutically. Indeed, Berg (2024) argued that EBP is on epistemically shaky grounds, and while randomised controlled trials, which are the holy grail of EBP, are informative, they do not equate to best practice. Moreover, Berg (2024: p. 858) argued that EBP relies on ‘epistemic one-sidedness’, which ‘often leads to epistemic injustice’. This article concurs with the argument about epistemic injustice. There was evidence of one-sidedness in the literature, because all that is considered EBP is limited to clinical trials. The socio-political–spiritual life of young survivors was missing. The analysis of how they are constructed as citizens, experiencers and survivors of violence and how this influences intervention was lacking. It is epistemically unjust to young citizens if we construct them, their experience of maltreatment and their responses to violence, abuse and neglect in a predominantly clinical framework, thereby ignoring the intersections of their multi-dimensional ways of being. It is also unjust if we are not epistemically privileging them to a more elevated state than is currently given to their knowledge in the scholarship. The fact that this article was written without input from young people, despite a genuine effort to do so, is a poignant example of the epidemic injustice that often exists between practice and research.

In the literature, young people were largely viewed through a victim lens. This view likely allows professionals to occupy the position of oracle in children and young people’s healing process, ignoring them as self-determined knowledge generators in their own healing process. To avoid this paternalistic approach, the canons of intervention in the lives of young survivors would benefit from a shift from a clinical trauma framework to a political framework: a political framework that recognises young survivors as citizens marginalised by their status, regards violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect as a source of political oppression, and acknowledges young survivors have a wealth of survival skills and knowledge.

Acknowledgements

I want to say a big thank you to the reviewers, whose comments were very insightful and helped me polish some aspects of this article.

References

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Balagopalan, S. (2019). Childhood, culture, history: Redeploying “multiple childhoods”. In S. Spyrou, R. Rosen & D. T. Cook (Eds). Reimagining childhood studies. (pp. 23–39). London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic.

Becker, K. D., Mathis, G., Mueller, C. W., Issari, K., & Atta, S. S. (2008). Community-based treatment outcomes for parents and children exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 8(1–2), 187–204. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/10926790801986122

Beetham, T., Gabriel, L., & James, H. (2019). Young children’s narrations of relational recovery: A school-based group for children who have experienced domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 34(6), 565–575. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-018-0028-7

Berg, H. (2024). Is evidence‐based practice justified? A philosophical critique. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 30(5), 855–859. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.14059 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39011890

Biwas, T. (2022). What takes ‘us’ so long? The philosophical poverty of childhood studies and education. Childhood, 29(3), 339–354. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/09075682221111642

Briere, J. (1996). Treatment outcome research with abused children: Methodological consideration in three studies. Child Abuse and Violence, 1(4), 348–352. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559596001004006

Burgon, H. L. (2011). ‘Queen of the world’: Experiences of ‘at-risk’young people participating in equine-assisted learning/therapy. Journal of Social Work Practice, 25(2), 165–183. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2011.561304

Burman, E. (2012). Deconstructing neoliberal childhood: Towards a feminist antipsychological approach. Childhood, 19(4), 423–438. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568211430767

Callaghan, E., Alexander, H., Sixsmith, J., & Fellin, L. C. (2018). Beyond “witnessing”: children’s experiences of coercive control in domestic violence and abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33, 1551–1581. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515618946 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26663742

Cannella, G. S., & Viruru, R. (2004). Childhood and postcolonization. Power, education, and contemporary practice. New York, USA: Routledge. DOI https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203463536

Capella, C., Lama, X., Rodríguez, L., Águila, D., Beiza, G., Dussert, D., & Gutierrez, C. (2016). Winning a race: Narratives of healing and psychotherapy in children and adolescents who have been sexually abused. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 25(1), 73–92. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2015.1088915 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26789104

Carroll, J. (2002). Play therapy: The children’s views. Child & Family Social Work, 7(3), 177–187. DOI https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2206.2002.00234.x

Cater, Å. K. (2014). Children’s descriptions of participation processes in interventions for children exposed to intimate partner violence. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 31, 455–473. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0330-z

Coates, L., & Wade, A. (2007). Language and violence: Analysis of four discursive operations. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 511–522. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-007-9082-2

Coholic, D., & Eys, M. (2016). Benefits of an arts-based mindfulness group intervention for vulnerable children. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33, 1–13. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-015-0431-3

Coholic, D., Lougheed, S., & Cadell, S. (2009a). Exploring the helpfulness of arts-based methods with children living in foster care. Traumatology, 15(3), 64–71. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765609341590

Coholic, D., Lougheed, S., & Lebreton, J. (2009b). The helpfulness of holistic arts-based group work with children living in foster care. Social Work With Groups, 32(1–2), 29–46. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/01609510802290966

Cooper, C., Booth, A., Varley-Campbell, J., Britten, N., & Garside, R. (2018). Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: A literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 85. DOI https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0545-3 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30107788

De Castro, L. R. (2020). Why global? Children and childhood from a decolonial perspective. Childhood, 27(1), 48–62. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568219885379

Dittmann, I., & Jensen, T. K. (2014). Giving a voice to traumatized youth-experiences with trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(7), 1221–1230. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.008 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24367942

Dunlop, K., & Tsantefski, M. (2018). A space of safety: Children’s experience of equine‐assisted group therapy. Child & Family Social Work, 23(1), 16–24. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12378

Eaude, T. (2023). Revisiting some half-forgotten ideas on children’s spirituality. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality, 28(1), 22–37. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/1364436X.2022.2136143

Fellin, L. C., Callaghan, J. E., Alexander, J. H., Harrison-Breed, C., Mavrou, S., & Papathanasiou, M. (2019). Empowering young people who experienced domestic violence and abuse: The development of a group therapy intervention. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(1), 170–189. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518794783 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30156129

Foster, J. M., & Hagedorn, W. B. (2014). Through the eyes of the wounded: A narrative analysis of children’s sexual abuse experiences and recovery process. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 23(5), 538–557. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2014.918072

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, USA: Continuum Books.

Gilligan, P. (2016). Turning it around: What do young women say helps them to move on from child sexual exploitation? Child Abuse Review, 25(2), 115–127. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2373

Goddard, C. (1998). Child abuse and child protection: A guide for health, educational and welfare workers. Melbourne, Australia: Churchill Livingstone.

Hammersley, M. (2017). Childhood studies: A sustainable paradigm? Childhood, 24(1), 113–127. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568216631399

Haslam, D., Mathews, B., Pacella, R., Scott, J. G., Finkelhor, D., Higgins, D. J., Meinck, F., Erskine, H. E., Thomas, H. J., Lawrence, D., & Malacova, E. (2023). The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment in Australia: Findings from the Australian Child Maltreatment Study. Brief report. Brisbane, Australia: Australian Child Maltreatment Study, Queensland University of Technology. DOI https://doi.org/10.5204/rep.eprints.239397

Hendrick, H. (1997). Children, childhood and English society, 1880–1990. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. DOI https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139171175

Huggard, L., & O’Connor, C. (2025). The impact of exposure to social explanations for depression on public stigma. Journal of Public Mental Health. DOI https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-03-2025-0042

Hughes, J., & Alcorn, C. (2001). Time limited group therapy for female adolescent survivors of child sexual abuse. Child Care in Practice, 7(4), 301–318. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/13575270108415338

James, A., & James, A. L. (2004). Constructing childhood: Theory, policy, and social practice. Palgrave Macmillan. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-21427-9

Jenks, C. (2005). Childhood. 2nd edn. New York, USA: Routledge.

Jensen, T. K., Haavind, H., Gulbrandsen, W., Mossige, S., Reichelt, S., & Tjersland, O. A. (2010). What constitutes a good working alliance in therapy with children that may have been sexually abused? Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice, 9(4), 461–478. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325010374146

Jessiman, P., Hackett, S., & Carpenter, J. (2017). Children’s and carers’ perspectives of a therapeutic intervention for children affected by sexual abuse. Child & Family Social Work, 22(2), 1024–1033. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12322

LeFrançois, B. A., & Coppock, V. (2014). Psychiatrist children and their rights: Starting the conversation. Children & Society, 28, 165–171. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12082

Malone, K., Tesar, M., & Arndt, S. (Eds) (2020). Theorising posthuman childhood studies. Singapore: Springer Nature. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8175-5

McManus, E., Belton, E., Barnard, M., Cotmore, R., & Taylor, J. (2013). Recovering from domestic abuse, strengthening the mother–child relationship: Mothers’ and children’s perspectives of a new intervention. Child Care in Practice, 19(3), 291–310. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2013.785933

McVeigh, M. J., & Oliveri, S. (2019). Threads across the world: Sewing resilience into the fabric of children’s lives. Social Work With Groups, 42(2), 117–126. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2018.1494668

Meyer, S., Atienzar-Prieto, M., Fitz-Gibbon, K., & Moore, S. (2023). Missing figures: The role of domestic and family violence in youth suicide – current state of knowledge report. Griffith University. hdl.handle.net http://hdl.handle.net/10072/422436

Miller, S. D., Hubble, M. A., Chow, D., & Seidel, J. (2015). Beyond measures and monitoring: Realizing the potential of feedback-informed treatment. Psychotherapy, 52(4), 449–457. DOI https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000031 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26641375

Moss, M., & Lee, A. D. (2019). TeaH (Turn ‘em around Healing): A therapeutic model for working with traumatised children on Aboriginal communities. Children Australia, 44(2), 55–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.1017/cha.2019.8

Mulder, M., & Wright, E. (2001). A partnership approach to group work with sexually abused adolescents. Child Care in Practice, 7(2), 116–129. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/13575270108415315

Nelson-Gardell, D. (2001). The voices of victims: Surviving child sexual abuse. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 18, 401–416. DOI https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012936031764

Nieuwenhuys, O. (2013). Theorizing childhood(s): Why we need postcolonial perspectives. Childhood, 20(1), 3–8. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568212465534

O’Connor, C., & McNicholas, F. (2020). Lived experiences of diagnostic shifts in child and adolescent mental health contexts: A qualitative interview study with young people and parents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48, 979–993. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00657-0 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32447487

Page, M., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuiness, L. A., Stewart, L. A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A. C., Welch, V. A., Whiting, P., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, 71. DOI https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33782057

Perry, S., & Frampton, I. (2018). Measuring the effectiveness of individual therapy on the well‐being of children and young people who have experienced abusive relationships, particularly domestic violence: A case study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 18(4), 356–368. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12184

Prout, A. (2005). The future of childhood. New York, USA: Routledge. DOI https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203323113_chapter_5

Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP Journal Club, 123(3), A12–A13. DOI https://doi.org/10.7326/ACPJC-1995-123-3-A12

Rose, N. (1999). Governing the soul. The shaping of the private self. New York, USA: Free Association Books.

Scott, J. C. (1990). Domination and the art of resistance. Hidden transcripts. New Haven, CT, USA: Yale University Press.

Sheffler, J. L., Stanley, I., & Sachs-Ericsson, N. (2020). ACEs and mental health outcomes. In G. Asmundson & T. O. Afifi (Eds). Adverse childhood experiences: Using evidence to advance research, practice, policy, and prevention. (pp. 47–69). New York, USA: Academic Press. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816065-7.00004-5

Thulin, J., Kjellgren, C., & Nilsson, D. (2019). Children’s experiences with an intervention aimed to prevent further physical abuse. Child & Family Social Work, 24, 17–24. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12476

Tseris, E. (2013). Trauma theory without feminism? Evaluating contemporary understanding of traumatized women. Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work, 28(2), 153–164. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109913485707

Ungar, M. (2017). Which counts more: Differential impact of the environment or differential susceptibility of the individual? British Journal of Social Work, 47(5), 1279–1289. DOI https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw109

Visser, M., & du Plessis, J. (2015). An expressive art group intervention for sexually abused adolescent females. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 27(3), 199–213. DOI https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2015.1125356 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26890401

Vizenor, G. (2008). Survivance. Narratives of native presence. Lincoln, NE, USA: University of Nebraska Press.

Wilson, C. A. (2012). Special issue of child maltreatment on implementation: Some key developments in evidence-based models for the treatment of child maltreatment. Child Maltreatment, 17(1), 102–106. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559512436680 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22357754

Woollett, N., Bandeira, M., & Hatcher, A. (2020). Trauma-informed art and play therapy: Pilot study outcomes for children and mothers in domestic violence shelters in the United States and South Africa. Child Abuse & Neglect, 107, 104564. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104564 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32512265

World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). Violence against women. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. who.int https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://childrenaustralia.org.au/journal/article/3061/#supplementary