Article type: Original Research

21 November 2025

Volume 47 Issue 2

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 12 November 2025

REVISED: 18 September 2025

ACCEPTED: 19 September 2025

Article type: Original Research

21 November 2025

Volume 47 Issue 2

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 12 November 2025

REVISED: 18 September 2025

ACCEPTED: 19 September 2025

![]() Exploring principles of trauma-informed care to strengthen service delivery for parents of children with complex support needs

Exploring principles of trauma-informed care to strengthen service delivery for parents of children with complex support needs

Carol J. Reid1 PhD, Research Coordinator *

Susan P. Caines2 BSW, Manager, Early Years & Disability

Chelsea Sofra3 BA(Public Health Promotion), Manager

Adrian Ingham2 Senior Disability Support Practitioner

Silver Keogh2 Integrated Family Services Practitioner

Lucinda Aberdeen4 PhD, Senior Research Fellow

Affiliations

1 Rural Health Academic Network, Department of Rural Health, University of Melbourne, Shepparton, Vic. 3630, Australia

2 FamilyCare, Shepparton, Vic. 3630, Australia

3 Goulburn Valley Centre Against Sexual Assault, Goulburn Valley Health, Shepparton, Vic. 3630, Australia

4 Access & Equity, Department of Rural Health, University of Melbourne, Shepparton, Vic. 3630, Australia

Correspondence

*Dr Carol J Reid

Contributions

Carol J. Reid - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Susan P. Caines - Study conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Chelsea Sofra - Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Adrian Ingham - Acquisition of data, Drafting of manuscript

Silver Keogh - Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Lucinda Aberdeen - Critical revision

Carol J. Reid1 *

Susan P. Caines2

Chelsea Sofra3

Adrian Ingham2

Silver Keogh2

Lucinda Aberdeen4

Affiliations

1 Rural Health Academic Network, Department of Rural Health, University of Melbourne, Shepparton, Vic. 3630, Australia

2 FamilyCare, Shepparton, Vic. 3630, Australia

3 Goulburn Valley Centre Against Sexual Assault, Goulburn Valley Health, Shepparton, Vic. 3630, Australia

4 Access & Equity, Department of Rural Health, University of Melbourne, Shepparton, Vic. 3630, Australia

Correspondence

*Dr Carol J Reid

CITATION: Reid, C. J., Caines, S. P., Sofra, C., Ingham, A., Keogh, S., & Aberdeen, L. (2025). Exploring principles of trauma-informed care to strengthen service delivery for parents of children with complex support needs. Children Australia, 47(2), 3060. doi.org/10.61605/cha_3060

© 2025 Reid, C. J., Caines, S. P., Sofra, C., Ingham, A., Keogh, S., & Aberdeen, L. This work is licensed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Abstract

Parents of children with complex support needs can experience multiple traumatic events that are ongoing and highly stressful. Extended exposure to trauma has adverse consequences on physical and mental health, leaving parents at high risk of developing complex trauma. To support all parents and promote their wellbeing, it is therefore critical that care systems, organisations and service-delivery approaches are trauma aware and trauma responsive.

This qualitative multimethod study involved a specific, government-funded parent support program delivered by a child and family service in regional Victoria, Australia. An organisational and program document analysis was undertaken along with interviews (n = 11) with parents and practitioners. Principles of trauma-informed care were used as a framework in deductive content analysis to identify the promotion or constraint of these core principles. Findings reveal trauma-informed care was promoted for parents during interactions with practitioners from the parent support program through relational strategies such as listening to parents and believing them. Frequent constraints were identified during interactions with the wider service system and workforce members external to the program. These potentially trigger or exacerbate parent trauma. Additionally, situations related to positive and negative impact for all practitioners were identified.

Data synthesis highlighted that although trauma-informed care was not explicitly stated as an approach by the organisation or in program service delivery, it was alluded to within strengths-based organisational values and program-documented practices. This was identified as a tension for the organisation because avoiding language with implied deficit connotations could lead to a failure to explicitly acknowledge trauma and its consequences.

This study provides insights about trauma-informed service delivery and practical ways trauma-informed care manifests in real-world practice. The findings are useful for decision makers developing organisational policies, in the design of education and training and for practitioners seeking to understand and actively implement trauma-informed care.

Keywords:

child and family services, parent complex trauma, principles of trauma-informed care, regional Australia, trauma-informed service delivery.

Introduction

Parents of children with complex support needs, such as medical conditions, physical difficulties, learning and developmental disabilities or neurodiversity, are at high risk of poor mental health outcomes such as high rates of depression and anxiety (Dewan et al., 2023; Griffin et al., 2024). Due to multiple and ongoing pressures, these parents can be impacted by traumatic stress (Dewan et al., 2023; Griffin et al., 2023; Holmes et al., 2024). Post-traumatic stress or complex trauma is accompanied by feelings of powerlessness and vulnerability. It occurs from the accumulation of repeated exposure to adversity potentially from a wide range of events (Lenain & Lever Taylor, 2023; Van Nieuwenhove & Meganck, 2019). It is not the event itself but how the person feels and experiences the event that determines the impact it has on an individual’s physical, psychological, social, emotional and/or spiritual wellbeing (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014; Herman, 1997; Kezelman & Stavropoulos, 2020). Interactions with health and social care service systems can inadvertently trigger, exacerbate or re-traumatise parents. To reduce these risks and support parents, it is essential that service-delivery approaches are trauma informed.

Trauma-informed care is a systemic approach to service conceptualisation and delivery that can be applied across service systems. These include health care, education, sport, justice, mental health, child welfare, first responder and crisis settings and in homelessness contexts. It can be incorporated into all types of workforce roles and practices as a universal, strengths-based approach to foster healing, aid recovery, reduce symptoms and prevent re-traumatisation (Hopper et al., 2010; Kezelman & Stavropoulos, 2020; Menschner & Maul, 2016; Piotrowski, 2019). A trauma-informed approach for parents of children with complex support needs acknowledges their experiences of trauma. It recognises the potential impact on their daily lives and wellbeing. The approach emphasises physical, psychological and emotional safety for both parents and service providers (Griffin et al., 2024; Hopper et al., 2010).

Trauma experienced by parents of children with complex support needs is cumulative. It can be exacerbated by feelings of grief and loss due to challenges with the parent–child relationship and representations of attachment (Griffin et al., 2023; Keenan et al., 2016; Lenain & Lever Taylor, 2023). Further, it can be triggered at key childhood milestones when parents must adjust and then continually readjust their hopes and dreams for their child’s future (Griffin et al., 2023; Keenan et al., 2016; Lenain & Lever Taylor, 2023). Parents can face feelings of hopelessness and despair when coping with a child’s severe behaviours or in situations of child-to-parent violence (Griffin et al., 2023, 2024). Parent wellbeing can also be adversely impacted by a sense of isolation from family members, peers and other support networks (Griffin et al., 2023, 2024).

Parents can be confronted with stigma and discrimination across a wide variety of systemic and social environments. They can encounter blame for their child’s ‘condition’ or have incidences of not being believed when they raise concerns regarding their child (Brymer et al., 2021; Dewan et al., 2023; Griffin et al., 2023, 2024). Adding to their burden, they are constantly asked to tell and retell their story (Brymer et al., 2021; Dewan et al., 2023; Griffin et al., 2023, 2024). Importantly, health and social care systems can inadvertently increase traumatic stress and re-traumatise parents. This may arise, for example, when navigating across siloed service settings, interacting with multiple agencies and negotiating for assistance with many different professionals (Brymer et al., 2021; Dewan et al., 2023; Griffin et al., 2023, 2024). There may be long waiting lists for services, barriers when seeking respite services or inaccessible, or a lack of services, particularly in rural locations – all of which can lead to parent exhaustion. (Brymer et al., 2021; Dewan et al., 2023; Griffin et al., 2023, 2024).

Adopting principles of trauma-informed care is an opportunity for the broader service system – which does not provide trauma-specific, specialist therapeutic services – to become trauma aware and trauma responsive at all levels of service provision (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014; Menschner & Maul, 2016). This must extend from strategic organisational policy development to the front reception desk interface (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014; Menschner & Maul, 2016).

The core principles for a trauma-informed system and associated service relationships include: physical and psychological safety; transparency and trustworthiness; choice and voice; empowerment; and collaboration (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014; Elliott et al., 2005; Harris & Fallot, 2001; Kezelman & Stavropoulos, 2020). Furthermore, respect for diversity and inclusion is essential, with a focus on addressing cultural, historical and gender issues (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014; Elliott et al., 2005; Harris & Fallot, 2001; Kezelman & Stavropoulos, 2020). The principles are not prescribed steps, but offer generalisable guidance across various types of settings (Kezelman & Stavropoulos, 2020; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015). The terminology and the application of principles are made more meaningful if adjusted to the specific setting or sector, thus highlighting the importance of adapting the principles to context (Kezelman & Stavropoulos, 2020; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015). Although they provide a platform, these principles can nevertheless be difficult to translate into real-world service-delivery strategies and workforce education and practices (Keesler et al., 2025).

This paper identifies interactions that promoted or constrained trauma-informed principles of care drawn from the experiences of parents and practitioners involved with a specific program. The aim was to explore these principles within this single-program environment to highlight ways to strengthen service delivery more broadly. The program, targeted at parents of children with complex disability support needs, is delivered in a regional–rural area of northern Victoria, Australia. ‘Interactions’ was selected due to previous research that identified that this term captured service–practitioner–parent communications, relationships and power dynamics within child welfare environments (Hall & Slembrouck, 2009; Merritt, 2020). This paper discusses strategies to acknowledge parent trauma and makes recommendations for further research. It contributes to policy and practice by emphasising the need for a more overt and embedded use of trauma-informed care.

Methods

The study was a multimethod design involving different qualitative data collection methods (Hesse-Biber et al., 2015). This included the selection and content review of organisational and program documents. Interviews were conducted with clients (parents) accessing the program, practitioners at the coalface of service delivery and workforce members external to, but associated with, the program. The benefit of utilising different qualitative data sources is to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the area being researched (Alejandro & Zhao, 2024). The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) provided guidance on detailing the study setting, program description and context, participant recruitment, data collection and analysis (Tong et al., 2007). The COREQ checklist assists with transparency (Tong et al., 2007) as exampled in the current paper by the comprehensive details provided under Data analysis (and see Appendix I).

Study setting

Geographical setting

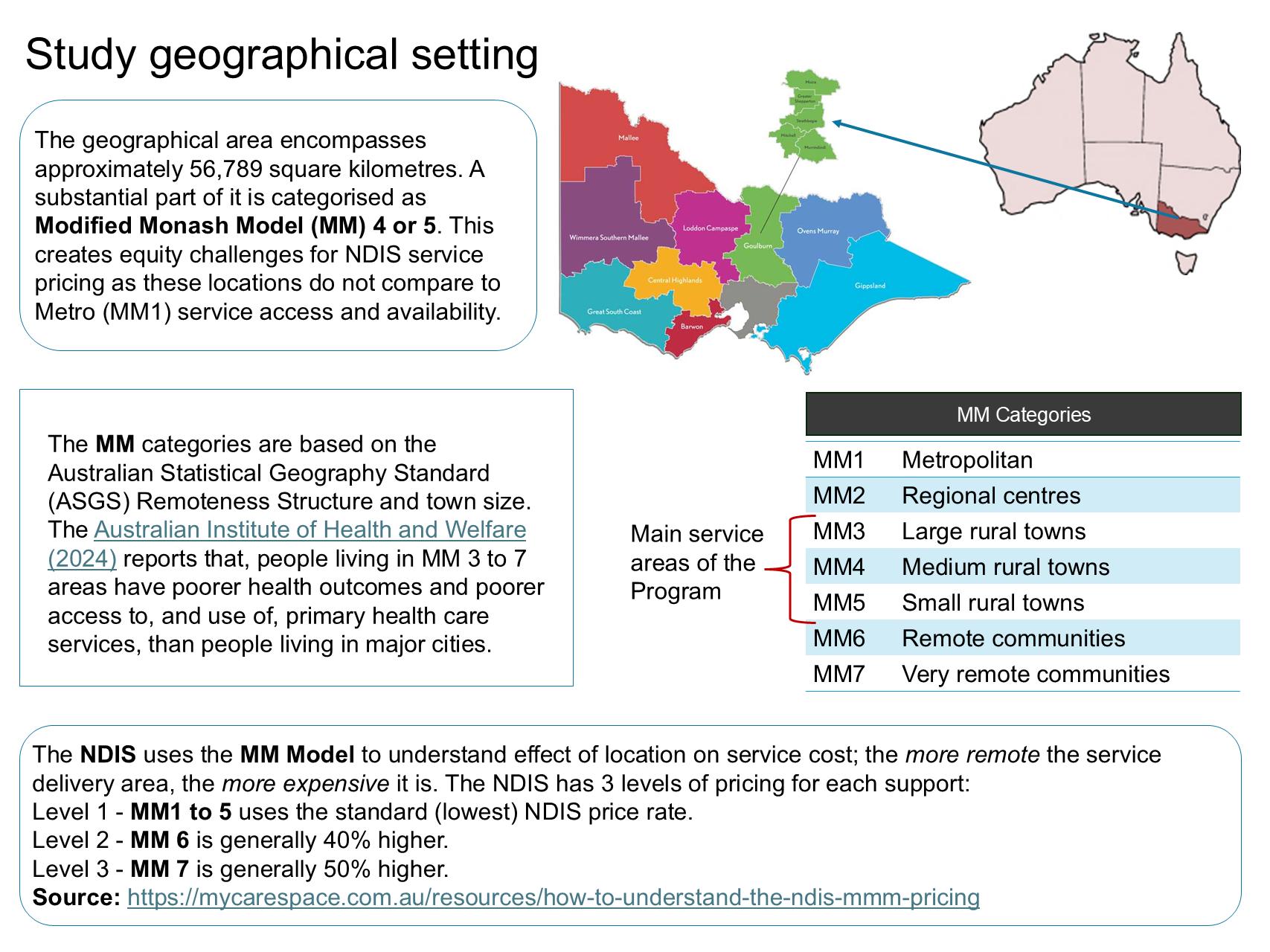

The geographical site for the study was a regional–rural area in northern Victoria, Australia. We used the Modified Monash Model (MM) categories (Versace et al., 2021) to highlight spatial access and equity challenges of where families lived and were provided with program service. Figure 1 outlines the setting.

Figure 1. Geographical setting and Modified Monash Model (MM) classifications (see Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024).

Program description and context

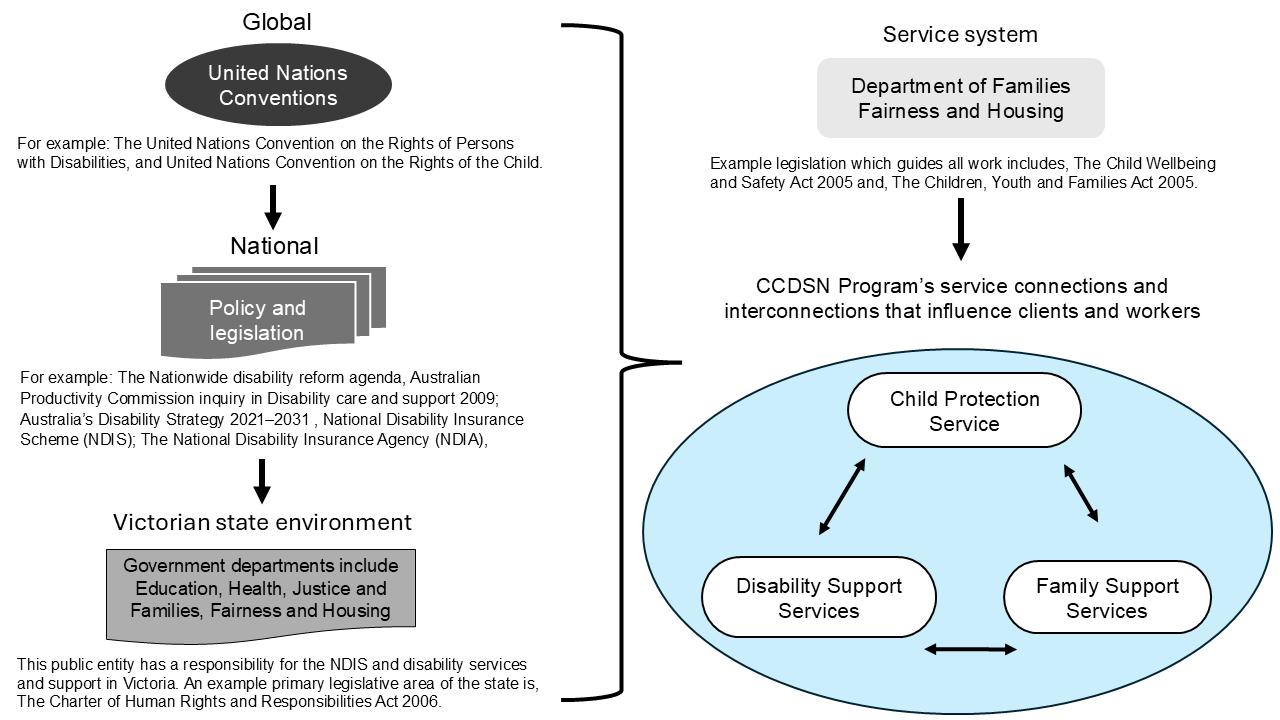

The Children with Complex Disability Support Needs (CCDSN) Program is a Victorian statewide initiative funded by the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH). In 2024, its name was changed to Parenting Children with Complex Disabilities (PCCD), but throughout this paper, it is referred to as CCDSN or the program. It began as a pilot initiative in 2019 to support families who are in the situation of relinquishing care or of family reunification. Interactions with families can occur across the major service areas of child protection, disability support and family and child support. Figure 2 acknowledges the multileveled, policy, legislative and system influences on the program model and Appendix II describes some of the details of these influences.

The goal of CCDSN is preventive, to keep children out of statutory care (Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, 2023). The program aims to achieve this through an intensive case management model that provides various support options. These include, for example, linking families to national disability support services and assisting with support plans, recommending and connecting families to a variety of services to relieve multiple parent stressors and building parent, family or child capacity. The site of the current investigation was a regional non-government, not-for profit child and family services organisation funded to provide the program within its service catchment.

The program model delivered by this organisation is unique because it uses a blended multidisciplinary team comprising a social worker and a disability support practitioner (FamilyCare Inc., 2023), whereas other sites known to the program team use a practitioner from a single discipline. The social worker, who is experienced in integrated family support, promotes the safety, stability and development of vulnerable children, young people and their families, with a focus on building capacity and resilience (Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, 2024a). The disability support practitioner assesses the world of their clients through a disability lens to identify and break down barriers and to promote inclusion of all persons with disabilities, a macro to micro approach inclusive of the social model and intersectionality principles (Brinkman et al., 2023; Spaan et al., 2024). The social model adopts a macro focus in that it recognises the role of disabling societal factors that fail to consider the needs and appropriate services for people with disability (Brinkman et al., 2023; Spaan et al., 2024). Intersectionality, with a micro focus, acknowledges an individual may have multiple oppressed or marginalised identities (e.g. culture, ethnicity, socio-economic status) that increase inequities (Brinkman et al., 2023; Spaan et al., 2024).

Figure 2. Policy, legislative and system influences on the program model

Participant recruitment

Participant groups targeted for this study were clients (parents) accessing the program, CCDSN practitioners involved with service delivery and workforce members external to but associated with the program. Recruitment of participants was facilitated by the organisation that delivered the CCDSN Program. A plain language statement, and a brief description promoting the study, accompanied all contact with potential participants. A specific client recruitment flyer was also made available to parents. Parents as clients accessing the program were informed by program staff about the opportunity to provide feedback. Negotiation then occurred between interested parents and a practitioner outside the specific program but working for the organisation who had built trust and rapport with parents. Program staff were recruited by emails circulated by a manager within the organisation. Those invited were current and former program staff members. Former staff were still working at the organisation but in other roles. The manager supplied emails (with permission after providing the plain language information) to external practitioners associated with the program for researchers to contact directly.

Data collection

The organisational and program document review encompassed, firstly, publicly available information from the child and family services organisation’s website (e.g. annual reports) and, secondly, program-specific material available internally to practitioners and provided to researchers. The public facing organisational materials were selected for analysis to examine the collective culture of the organisation as the service-delivery context. These were foundational to establish a philosophy of trauma awareness and responsiveness as part of the organisation’s core values and, as such, underpinning all policies, strategies and procedures (Kezelman & Stavropoulos, 2020). The internal documents included the Program Manual, Program Framework the service data reports to the funder. These samples of documents were selected for content analysis because they would support trauma-informed care practice.

Semi-structured individual interviews were undertaken by Author 1, who did not have a previous relationship with participants. These were either face to face at a mutually agreed upon location, or via a cloud-based videoconferencing medium (Zoom or Microsoft Teams) using only the audio recording function. Interview questions for parents asked about their experiences and helpful or unhelpful aspects they found from their connections with services and the program. Interview questions for all practitioners included asking about service and program barriers and enablers (for their clients and themselves as workers) and any negative and positive experiences. Interview questions were useful to guide and prompt but not inhibit conversations. Questions are listed in Appendix III.

Data analysis

Analysis of the documents involved deductive content analysis whereby concepts were drawn from the written information and aligned with the principles of trauma-informed care. The six common core principles of trauma-informed care that were used as a framework are outlined in Table 1. These descriptions have been paraphrased from publications from Blue Knot Foundation (Kezelman & Stavropoulos, 2020), and Orygen (Scanlon et al., 2018), as Australian peak bodies, and the seminal work of the American organisation, SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015). To record information from the document review, a table developed in Microsoft Word was utilised.

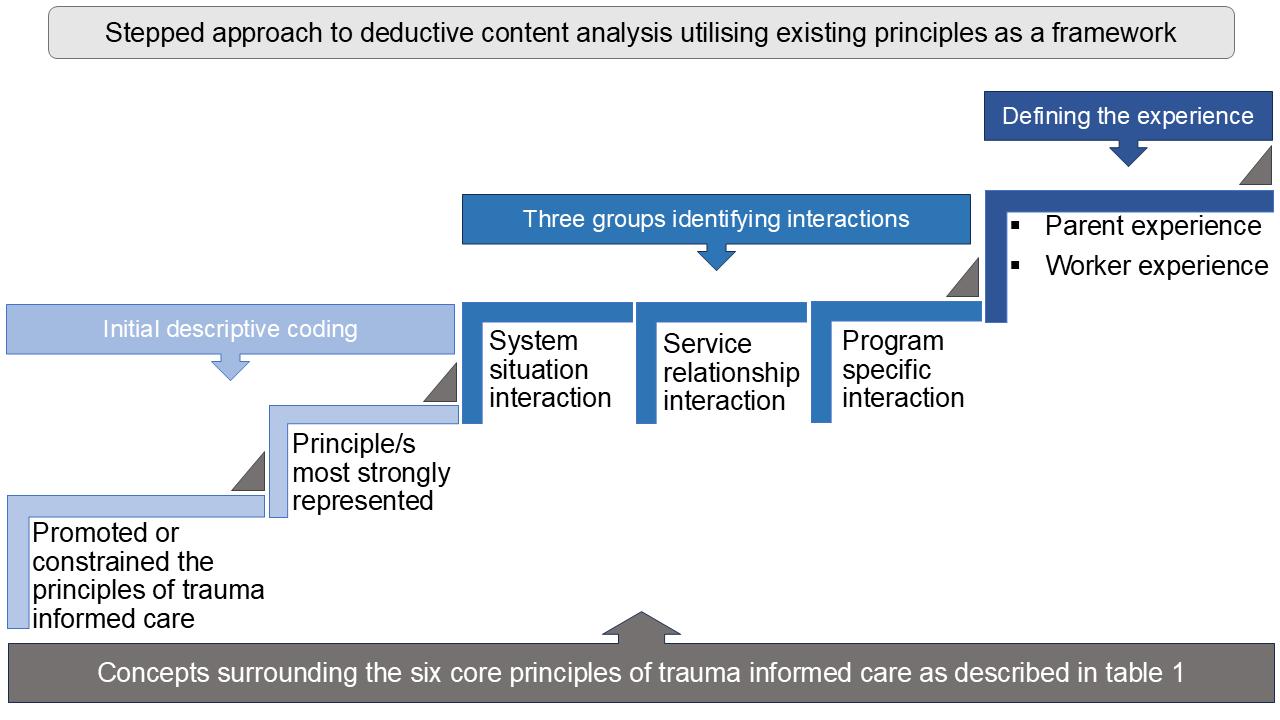

Interview recordings were transcribed to text by the first author and a unique identifier was attached to each transcript to protect anonymity (e.g. #P01). Transcripts were analysed using a deductive approach as depicted in Figure 3, using the principles of trauma-informed care as a framework (see Table 1). Interpretation of the interview data was undertaken by two authors, then reviewed independently by a third with expertise in the topic area, and final agreement was gained through group consensus (Krippendorff, 2019; Vaismoradi et al., 2013). The deductive analysis involved coding text that described when concepts of trauma-informed care were promoted or constrained, and which principle was most strongly represented. Stepped refinement then occurred into groups describing interactions, which identified a system situation or service relationship or a program-specific interaction. Experiences were then, finally, defined as a parent or worker experience.

Table 1. Principles of trauma-informed care descriptors

| Principle of trauma-informed care | Description |

|---|---|

|

Safety |

This principle guides the organisation and all its staff to ensure physical and psychological safety is inclusive of both the physical environment of the service setting and the emotional situations where interpersonal interactions occur within the service relationship. |

|

Transparency and trustworthiness |

This principle recommends organisational operational decisions are transparent to ensure trust amongst clients and staff. There is then clarity for everyone about managing expectations and understandings about who will do what, when and how, within the scope of service provision and delivery. |

|

Choice and voice |

This principle acknowledges that, where possible, clients should have choice at all levels of service. It recognises that an individualised approach is essential, because every person’s experiences are unique to them. |

|

Collaboration |

This principle shows awareness about power differences in all service interactions but when true partnering occurs there is meaningful sharing of power and decision making. Additionally, it refers to communicating in ways that convey doing ‘with’ rather than doing ‘to’ or ‘for’ clients. |

|

Empowerment |

This principle promotes the idea that recognising and building on people’s strengths and their capacities to develop new skills and to be active in their own service planning, reduces potential power imbalances when interacting with services. |

|

Respect for inclusion and diversity |

This principle acknowledges that, although trauma is pervasive, it can be experienced differently; for example, by people of different genders, cultures, ages or socio-economic status or due to historical trauma, such as the intergenerational trauma of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples or war, conflict, torture and trauma experienced by individuals with a refugee or asylum seeker background. Organisations should incorporate policies and procedures that are, for example, culturally sensitive or gender responsive. |

Figure 3. Deductive approach used for the text analysis

Ethics approval

Parents are a vulnerable group and their safety was a priority in the study’s ethical considerations. To minimise any potential risk to this group and reduce power imbalances, the interviews were conducted by an external, impartial researcher. Assisted by the plain language statement, the researcher ensured parents understood that any critical feedback would not have an impact on service access or future support.

The study received ethical approval from the University of Melbourne, Office of Research Ethics and Integrity (approval reference ID: 2023-27457-43327-3). All participants provided informed consent prior to being interviewed. Parent participants were given a $50 voucher to thank them for their time.

Findings

The presentation of the study’s findings commences with a table of service-delivery data (Table 2) providing total program client numbers for the consecutive periods of 2020–2021, 2021–2022 and 2022–2023 and total overall figures. It includes information about the geographical reach of the program.

Program client characteristics varied. Family situations included two-parent families, single-parent, grandparent and stepparent arrangements. Two parents were from a migrant and refugee background. The age range for children with complex needs was 6–15 years old. The child client group included 15 males and seven females. Three families had more than one child with complex disability support needs. Most (81%) families lived in category MM3–MM5 areas (refer to the descriptors in Figure 1).

Table 2. Program service-delivery data

MM, Modified Monash Model

| Reporting year | Families | Service hours | Client characteristics | Program reach | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | Child/ren with complex needs | Siblings | MM categories overall | |||

|

MM1: 3 families |

||||||

|

2020–2021 |

6 |

1,718 |

9 |

9 |

6 |

MM3: 7 families |

|

2021–2022 |

7 |

1,154 |

13 |

9 |

8 |

MM4: 4 families |

|

2022–2023 |

4 |

945 |

7 |

4 |

13 |

MM5: 3 families |

|

Total |

17 families |

3,817 hours |

29 parents |

22 children |

27 siblings |

Four local government areas |

Document-review analysis findings

A summary of document-review findings is provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Organisational and program document review summary of findings

| Source of document for text content analysis and areas examined | Narrative on key points from the qualitative content analysis | Principles promoted or constrained |

|---|---|---|

|

Public Organisational website Areas: Values; service delivery statements; Major strategies/plans promoted |

The organisational vision had a focus on increasing wellbeing and building strengths. The listed values were statements about respect, empowerment, integrity, leadership communication and professionalism. The commitment to service delivery to children was about ways the organisation will provide respect, voice, trust, information, help and safety. The organisation’s access, equity and inclusion strategy 2024–2029, included statements and associated actions regarding access, service delivery, participation and transparency; this applied to clients and the workforce. The reconciliation action plan (RAP) and its five dimensions of reconciliation (race relations, equality and equity, institutional integrity, unity and historical acceptance), fostered acknowledgement of cultural, historical and intergenerational trauma. |

Overall, a strengths-based approach was emphasised by the organisational website and public facing documents that promotes the principles. There were no explicit statements about the organisation as ‘trauma aware’, ‘trauma responsive’ or that a trauma-informed approach to service delivery is embedded in all programs; however, it was strongly implied. |

|

Public Organisational Annual Reports Areas: growth, service-delivery approaches, outputs and outcomes |

The organisational annual reports were congruent with the website content as described above. Nine reports were available that gave a historical timeline about positive organisational growth and continued updating and advancement of service delivery and programs. Staff profiles and client journeys provided examples of the organisation’s service-delivery approaches and outcomes they achieved. Service-delivery data were provided, and client feedback was in numerical format with example quotes. |

Similar to the organisational website, there were no explicit statements about the organisation as ‘trauma aware’, ‘trauma responsive’ or that a trauma-informed approach to service delivery is taken; however, it was, again, strongly implied. The written language was strengths based, acknowledging the resilience and skills of staff and clients. |

|

Internal Organisational Program Manual. Areas: entire document |

This document provided overall guidance about the program; it included a service overview, policy and quality requirements (as also described by Figure 2), theoretical approaches to roles and responsibilities of the team, referral pathways, record management and monitoring of client feedback. An explicit statement in roles and responsibilities of the team leader highlighted the need for ‘Sound knowledge of theoretical and practice frameworks relating to child development, trauma and attachment and disability’. Team leader skills in supervision were noted along with the supervision process for staff. |

The organisational Program Manual promoted the principles. It implied the program would take a trauma-informed approach to service delivery and included a specific statement that acknowledges the impact of trauma. It promoted the safety of the workforce, particularly in outlining the supervision process. Time is allocated for reflective supervision to assist with secondary or vicarious trauma. |

|

Internal Organisational Program Framework Areas: entire document |

This document complemented the Program Manual and was more a technical description with information about standards. In tabulated format, it provided alongside each element (e.g. intake, allocation, assessment, case work), an explanation about the associated family service requirements. It provided clear guidance for all practitioners. |

The organisational Program Framework document promoted the principles because it provided a clear platform about how service delivery is conducted. Although not explicitly stated, it promoted transparency, trust and collaboration. In addition, it promoted the safety of the workforce. |

|

Internal Organisational program reports to funder to meet requirements and comply with targets (2020–2021 and 2021–2022) |

Of note is that the report format was not created by the organisation. The two reports to DFFH that were examined were in narrative formats capturing the depth of intensive case management involvement. They provided descriptions of referrals placed, coordination and support organised, advocacy undertaken, and strategies to assist families. Importantly, they gave explanations regarding parents’ views about the goals reached and outcomes of the intensive case management intervention. |

The program’s reporting clearly gave a range of examples where the principles were promoted in the two reports to DFFH. The reports provided narratives about safety, collaboration (workforce and parents), and how the choices, voice and empowerment of parents were increased. |

|

Internal Organisational program report to funder (2022–2023) |

As requested by DFFH, the reports were numerical only, responding to thirteen questions about the numbers of people associated with aspects of service delivery. |

This report format constrained all principles of trauma-informed care. The voices of parents and the workforce were absent. |

Interview findings

In total, 11 interviews were completed, all individually; a summary of participant characteristics is presented in Table 4. Following this table, findings are provided under two main subheadings: Interactions that promoted principles of trauma-informed care and Interactions that constrained principles of trauma-informed care. These are further refined according to their alignment with the principles, then grouped as interactions pertaining to a system situation, or service relationship or if it was program specific, and then defined as a parent or worker experience. Figure 3 outlines the analysis approach.

Table 4. Interview participant characteristics (n = 11)

| Participant characteristics, summarised as groups | n |

|---|---|

|

Parents as clients of the program (adults over 18 years of age) The parents came from varied circumstances, including single-parent situation, refugee background, single child, more than one child with complex needs. Three interviews were with mothers/grandmother, and one was with both parents and grandparents with limited English language. |

4 |

|

Program practitioners Interviews involved one former and two current staff members, and a program manager. Two were social workers and two were disability support practitioners. |

4 |

|

External workforce members associated with the program The workers interviewed were from organisations that organise support services. Their occupational backgrounds varied and included teaching, social work, carer support coordination, counselling and coordinating disability support accommodation. |

3 |

Interactions that promoted principles of trauma-informed care

Commencing with interactions that were positive for parent wellbeing and/or supported the workforce, findings are presented on the basis of their alignment with a principle of trauma-informed care.

Situations that promoted the principle of choice and voice for parents

Situations that promoted the concepts of choice, voice and control for parents were found to be emphasised in interactions specific to the program. The CCDSN Program ethos was to look at the whole family unit and to consider the individuals within it. Examples of this occurred during service interactions, such as assessment, planning of goals, organising care team meetings and ensuring parents are included in these, along with when arranging referrals, undertaking advocacy and sourcing services and support workers that best fitted with individual needs. The program practitioners recognised and responded to the overwhelming stress and burden facing families and prioritised their physical and psychological wellbeing. A key relational strategy that they utilised was listening to the parents, believing what they said and not blaming parents for their situation, their child’s disability or for their struggle. One program practitioner spoke about this:

The first place we start at is just believing families because unfortunately their journey has often been dismissed and there’s always that underlying assumption that it’s a parenting thing and not a disability thing. Child protection always start from a place of assuming that there are parenting issues. I think unfortunately the journey for a lot of families with children with complex disability needs is they go through their whole journey not being believed. (#P02)

Situations that promoted the principles of collaboration and empowerment for parents

The two principles of collaboration and empowerment were found to be promoted in specific interactions with the program. Parents and all workers interviewed gave examples of how these principles were activated in practical situations, particularly where the program’s practitioners organised and facilitated care team meetings and when workers accompanied parents to appointments in other settings, such as health or education. This advocacy strengthens exhausted parent’s coping skills and capacity. It can model to parents possibilities in addressing power imbalances. The following parent experience is an example:

… just the emotional support has been amazing. I’ve got some reassurance that I was doing okay … to have that support … She [program practitioner] attended the meetings with me and made me aware of what was actually out there. I felt like I wasn’t doing it on my own. I haven’t had any support like that before. They [worker name] came to advocate for us at a paediatrician appointment, and she didn’t leave anything go. I would have left it, thinking oh well … She was onto everything and didn’t let anything slip. And she did a lot of the leg work looking for a paediatrician. She did all that research … I quickly learned to know what’s the best thing for us. (#P08)

Situations that promoted the principle of collaboration and empowerment for the workforce

Interactions with the CCDSN Program team supported the principle of collaboration and empowerment for external workforce members. The beneficial impacts for them included increasing their feelings of value and worth, and positive views about their professionalism. Collaboration increased their role satisfaction when they felt they were part of a multidisciplinary approach that focused on the best outcomes for the whole family unit. It additionally increased their skills; for example, in understanding the difference between parental full-time responsibility of care and part relinquishment. This is where a child is in out-of-home care arrangements some of the time. For example, as one external worker described this situation as follows.

I found it really helpful, and it’s also taken a little bit of pressure off me as well, to have somebody backing me up. I’ve also picked up little tricks of the trade and how to escalate things through unusual channels or the not so much travelled channels. And definitions too, some of those intricacies have been interesting to learn and it’s helped me in other […] areas. These are things that aren’t written down anywhere, you can’t look up online. It’s just through having conversations with people with child and family service’s backgrounds, so I absolutely think it’s been great for collaboration. And me being able to help more people. (#P05)

Situations that promoted the principle of respect for inclusion and diversity of parents

The principle of respect for inclusion and diversity of parents was found to be promoted in situations specific to the program. An example given by a workforce member external to the CCDSN Program highlighted that the program operated by assigning a consistent worker to a family who has a responsibility to pursue culturally sensitive practice. This allowed program practitioners to connect with culturally diverse parents and build culturally safe collaborations by developing trust, respect and rapport to then facilitate the identification of the family’s unique needs. As this worker highlighted:

The program worker is mindful about connecting to the Ethnic Council [local organisation that can educate services about cultural diversity and inclusion] because they need to see the cultural side of things in order to unpack their needs they need to be connected culturally and they need to feel respected, culturally respected. The workers are mindful about that. And then they have advised me to do so and that has really helped. (#P06)

Interactions that constrained trauma-informed principles of care

Interactions that constrain the principles of trauma-informed care can potentially or inadvertently re-traumatise, trigger or exacerbate trauma symptoms and adversely impact complex trauma.

Situations that constrained the principle of safety for parents

Physical and psychological safety for parents, child/ren with complex needs and their siblings is paramount in the type of service setting described in this study. A situation where the system failed child and parent safety is described by a practitioner:

They actually took [child’s name] away, told me they were taking [child] to a facility in Melbourne to [be] assessed and diagnosed and took [child] to a foster home. And then brought [child] back on Monday and left [child] on the doorstep. That organisation put a very sour taste in my mouth. (#P08)

Situations that constrained the principle of safety for workers

Trauma-informed care emphasises physical, psychological and emotional safety for both clients and service providers. There were system barriers that generated circumstances where workforce members would experience traumatic stress and burnout. All worker interviewees described feelings of frustration and helplessness and situations of demanding workloads and limitations on the scope of their role that prevented them undertaking family, parent or client advocacy. A support plan coordinator described their experiences as follows:

You just have basic services on NDIS, sometimes I feel pretty helpless. I couldn’t do much in the absence of sufficient funding plus accessing other additional supports they require. We have restrictions on support hours and funding. The funding we are provided is not enough to have a helpful impact on the family. And there are certain roles we cannot step into with the family, the support is for the client, not for the family. I sometimes feel that I wish I could help the family but due to our limitations and scope of role we can’t do that. (#P05)

Another NDIS support coordinator indicated impact on their identity as a professional due to system interactions. They described recognising families at risk due to complex disability and complex family needs, but without the child protection needs, for whom they could not negotiate a suitable referral pathway, as the example below highlights.

I’ve got a huge caseload because there’s so many people in need. There’s been times where the capacity of my role has been misunderstood, what’s within my role. I can really only advocate for families within the limits of support coordinator, which doesn’t hold as much weight as somebody who has the complex family and social worker background. I’ve got families that could desperately use the program’s help, the expertise the team provides, but it’s just not possible to refer directly. (#P06)

Rural location had physical and psychological safety impacts on all workforce members, and this was associated with CCDSN Program sustainability issues. Travel distances were highlighted, with the program practitioners often undertaking a 4-hour round trip to complete a family assessment. There were employment concerns with uncertainty about the continuation of funding that arose when this study was undertaken and there was frustration with service provision inequities, all potentially contributing to workforce vicarious trauma. One external worker made the following comparison.

I’ve lived in Melbourne all of my life and only been in rural Victoria the last 18 months. But there’s a clear gap between services. It’s hard to get things even like speech or any allied health professional in Melbourne, but it’s 10 times harder in rural Victoria. There’s lots of mental health, complex families, disability services in Melbourne, but there’s not that availability here. (#P06)

Situations that constrained the principle of trustworthiness and transparency for parents

System interactions for parents constrained the principle of trustworthiness and transparency. Parents and all workforce members described different scenarios where this occurred. Parents spoke about the inconsistency and unreliability of the service system, the gaps and their exhaustion when navigating a system that was complicated and lacked clarity. An experience of a parent highlights system failure in being trustworthy or transparent:

… they keep sending new people. We had the head of the family violence from child protection, two come in and they absolutely promised me the world. They said, ‘We’re going to get this sorted, this is not how our organization works, we’re going get some help’. I didn’t hear from them again, not a boo. Nothing. Nothing. He said to me ‘you will hear from me within the week’, that didn’t happen, it was disappointing, and it did put me off. (#P08)

A program practitioner gave another example that emphasised a system that is not transparent for parents:

We found that the families don’t understand the plans. They were given these plans that weren’t sufficient, and then they weren’t told how to use them. They weren’t told who to contact if they don’t know how to use them. Then a lot of them may not have had support coordination. They literally just got a piece of paper and had no idea what to do. (#P01)

Situations that constrained the principle of respect for inclusion and diversity of parents

Parents and workforce interviewees related experiences in which the principle of respect for inclusion and diversity was compromised. These could be identified as mainly occurring in service relationship interactions. Situations were recounted in an interview with a program practitioner where judgmental commentary occurred about a large family alongside their refugee background. This was experienced by the practitioner when organising referrals and connecting the family to a variety of supports, with comments from other workforce members such as, ‘why would they have so many children’. This family experienced stigma and blame about their situation and for their child’s disability and associated complex behaviours. During an interview for the study, this mother shyly sat beside the first author and asked in halting English if I knew about malaria. She spoke about living in a refugee camp where her son contracted malaria at 2 years of age and her worry as she sat with him and his condition deteriorated as his temperature continued to rise. The child’s condition was cerebral malaria, which resulted in an acquired brain injury with long-term neurocognitive impairments. The impact now is the child currently cannot live full time with the family due to emotional, physical and medical safety concerns for the whole family (including the child). This powerful story highlights how insights about intersectionality require embedding in the principle of inclusion and diversity. It is an example of how this mother wanted their story to be heard and understood and not judged or misrepresented.

Discussion

This paper described interactions that promoted or constrained the principles of trauma-informed care for parents of children with complex support needs. The findings highlight how the specific program and its practitioners fostered these principles. It identified wider service system experiences that would exacerbate or further trigger trauma for parents. These included where workforce members external to the CCDSN Program lacked trauma awareness or responsiveness. The study additionally identified situations that impacted on all practitioners and positively or negatively increased their stress.

This examination has emphasised complexity for a program operating across three main service areas, namely, Child Protection, Disability Support and Family Support Services (see Figure 2). Parents of children with complex support needs were also caught up within this challenging array of service settings. The overall findings accentuate the pervasiveness of trauma experiences due to engagement with services for parents. These require deeper acknowledgement at all levels, from policy to practice, particularly in service environments where reform is occurring. Researchers have found that improvements in client outcomes in past national efforts in service redesign have been unpredictable or impacted by sustainability issues (De Oliveira, 2023; Frimpong-Manso, 2021; Silburn & Lewis, 2020).

Previous examinations surrounding the design and development of the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme have questioned whether concepts such as safety, transparency, voice, empowerment, collaboration and intersectionality have been fully recognised (Carey et al., 2018; Horsell, 2023; Thill, 2015). Although not explicitly named as constructs of trauma-informed care, such critiques further emphasise that increases in parent trauma experiences through interactions with systems designed to support them remains unrecognised. This is a critical gap when translating reform policy into all levels of service interactions.

The principles of trauma-informed care as outlined are not clear strategies to implement in discrete steps. The findings of this study stress that to operationalise into practice, the principles must be immersed into all interactions to then provide meaningful trauma-informed approaches to service delivery. It is important to formally articulate the principles of trauma-informed care into an organisation’s values, service-delivery policies, programs and practices, accompanied by explicitly stated guidance and expectations. Such an approach would then increase awareness of and responsiveness to parent trauma. Clear statements additionally acknowledge the need for support for workforce members with stress, burnout and vicarious trauma, which the study findings also found to have occurred.

This analysis highlights that trauma-informed care was alluded to within strength-based organisational values and the program practice framework and guidelines. It identified a potential tension for organisations in that avoiding deficit-seeming language can lead to a failure to openly acknowledge trauma and its consequences. A trauma-sensitive approach assists the service provider to shift from a deficit focus of ‘How do I understand this problem or symptom?’ to the more holistic, person-centred view of ‘How do I understand this person?’ (Harris & Fallot, 2001: p. 13). Adopting this type of service-delivery perspective supports approaches that validate a person’s experience and promotes constructive views of those impacted by trauma (Herman, 1997). More recently, to increase awareness and recognition of trauma resilience, the evidence-based Power–Threat–Meaning Framework has been developed (Johnstone & Boyle, 2018). It provides a conceptual system to further reflect on and consider what’s happening for a person, rather than the pathologised and deficit labelling of what’s wrong about this person or their situation (Johnstone & Boyle, 2018).

Limitations

This study had several limitations, namely that a small number of participants were involved, and it focused on one specific program delivered in a particular geographical location. The experiences of parents and workforce members should not be considered homogeneous; they are unique reports from individuals within distinct sets of circumstances. The analysis framework was author designed amongst a multidisciplinary group (Authors 1, 2 and 3) from evidence-based sources and would benefit from further testing in a larger study with different services engaging with parents of children with complex needs and in a variety of geographical locations. The framework and analysis approach are, however, a useful way to further examine and understand parents’ and practitioners’ experiences within a service system that may trigger, exacerbate or re-traumatise.

Conclusion

This study provides important insights about trauma-informed service delivery in a regional–rural Australian context and practical ways trauma-informed care manifests in real-world practice. It raises awareness about parent experiences during service delivery and how, when interacting with care systems and the workforce, trauma impact may be inadvertently increased. The study emphasises a tension for organisations in decisions about explicitly stating and advocating for approaches to service delivery that are trauma aware, trauma responsive and that provide trauma-informed care.

Knowledge translation and impact: Implications, recommendations and future research

There are implications from this study for decision makers developing organisational policies within any health, welfare or other care settings and for practitioners seeking to understand and actively implement trauma-informed care. Organisations can utilise the core principles as a framework to develop a contextually relevant policy for their approach to trauma-informed service delivery that aligns with their organisational values and operating environment. Practitioners from multidisciplinary backgrounds could use this study to examine their own practice and discuss in supervision or with their peers what trauma awareness and trauma responsiveness looks like for them in their practice contexts. Further, the study findings will be useful in the design of education and training about trauma-informed care for parents of children with complex support needs. The examples drawn from the interviews would be useful as scenarios for group discussions in workforce training.

Engaging with a trauma-specific therapeutic service is recommended to assist organisations to develop a common language about the pervasiveness of trauma and its consequences. This would assist to purposefully frame trauma-informed care as embedded at all levels of the system’s networks, referral pathways and services. Moreover, such a collaboration could provide education locally for all workforce members to increase skills in identifying indicators of trauma in the clients they serve (Keesler et al., 2025). This would clearly acknowledge and promote approaches that are trauma aware and trauma responsive. It is essential that future studies continue to consult closely with parents of children with complex needs to enable universal trauma-informed approaches to service delivery and to develop ways in which all sectors can be improved to comprehensively support parents.

Acknowledgements

This study was undertaken on the unceded lands of the Yorta Yorta Peoples. The authors acknowledge the Traditional owners of the land and pay our respects to all Elders past and present.

The authors thank all participants for sharing their experiences and their time in engaging with us in this study. The project acknowledges the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training programme.

Reflexivity statement

The preparation of this manuscript was a collaborative undertaking with practitioners from the child and family services sector, a topic area expert from a specialist therapeutic service and researchers from a university department of rural health. Authors have backgrounds in social work, health promotion, youth work, disability support and sociology. Some have lived experience of caring for family members with complex needs. Author contributions were as follows. CR: conceptualisation of study, study protocol and design development, ethics submission, data collection, analysis and interpretation of findings, first draft of manuscript, subsequent refinement and editing. SC: data analysis, interpretation and findings, reviewing and editing of manuscript. CS: analysis framework, topic area expertise, reviewing and editing of manuscript. AI: data collection, reviewing and editing of manuscript. SK: reviewing and editing of manuscript. LA: reviewing and editing of manuscript.

Funding statement

No funding was received in the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest identified by the authors. All authors approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on specific request from the corresponding author. Raw data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Alejandro, A., & Zhao, L. (2024). Multi-method qualitative text and discourse analysis: A methodological framework. Qualitative Inquiry, 30(6), 461–473. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004231184421

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2024). Rural and remote health. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. aihw.gov.au https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health

Brinkman, A. H., Rea-Sandin, G., Lund, E. M., Fitzpatrick, O. M., Gusman, M. S., Boness, C. L. & Scholars for Elevating Equity and Diversity. (2023). Shifting the discourse on disability: Moving to an inclusive, intersectional focus. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 93(1), 50–62. DOI https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000653 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36265035

Brymer, M., Gurwitch, R., & Briggs, E. (2021). Assisting parents/caregivers in coping with collective traumas. Los Angeles, CA, USA: The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. nctsn.org https://www.nctsn.org/resources/assisting-parents-caregivers-in-coping-with-collective-traumas

Carey, T. A., Sirett, D., Russell, D., Humphreys, J. S., & Wakerman, J. (2018). What is the overall impact or effectiveness of visiting primary health care services in rural and remote communities in high-income countries? A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 476. DOI https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3269-5 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29921271

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57. Rockville, MD, USA: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24901203

De Oliveira, B. (2023). A thematic analysis of homelessness practitioners’ perception of the impacts of welfare reforms in the UK: “Hard to maintain my own mental equilibrium”. Housing, Care and Support, 26, 65–83. DOI https://doi.org/10.1108/HCS-10-2022-0027

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing. (2019). Children, youth and family services new funding model. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Government. providers.dffh.vic.gov.au https://providers.dffh.vic.gov.au/child-and-family-funding-reform

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing. (2020). Child Protection Manual – Placement in a secure welfare service – advice. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian State Government. cpmanual.vic.gov.au https://www.cpmanual.vic.gov.au/advice-and-protocols/advice/out-home-care/placement-secure-welfare-service-advice

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing. (2022). Alliance planning and oversight policy for child and family alliances. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Government. providers.dffh.vic.gov.au https://providers.dffh.vic.gov.au/alliance-planning-and-oversight-policy-child-and-family-alliances-word

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing. (2023). Program requirements for children with complex disability support needs in Victoria. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Government. providers.dffh.vic.gov.au https://providers.dffh.vic.gov.au/program-requirements-children-complex-disability-support-needs-victoria

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing. (2024a). Children, youth and families: Family services. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Government. providers.dffh.vic.gov.au https://providers.dffh.vic.gov.au/family-services

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing. (2024b). Our structure. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Government. dffh.vic.gov.au https://www.dffh.vic.gov.au/our-structure

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing. (2025). Website. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Government. dffh.vic.gov.au https://www.dffh.vic.gov.au

Dewan, T., Birnie, K., Drury, J., Jordan, I., Miller, M., Neville, A., Noel, M., Randhawa, A., Zadunayski, A., & Zwicker, J. (2023). Experiences of medical traumatic stress in parents of children with medical complexity. Child: Care, Health and Development, 49(2), 292–303. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.13042 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35947493

Elliott, D. E., Bjelajac, P., Fallot, R. D., Markoff, L. S., & Reed, B. G. (2005). Trauma‐informed or trauma‐denied: Principles and implementation of trauma‐informed services for women. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(4), 461–477. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20063

FamilyCare. (2023). Children with Complex Disability Support Needs (CCDSN) Progam Manual. Shepparton, Australia: FamilyCare.

Frimpong-Manso, K. (2021). Family support services in the context of child care reform: Perspectives of Ghanaian social workers. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 38(2), 157–164. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00729-6

Griffin, J., Finch, E., Yakeley, M., Bonger, N., & Villierezz, P. (2023). Difficult parent or traumatised parent? British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy: Children, Young People and Families, December 2023, 20–23. affinityhub.uk https://www.affinityhub.uk/wp-content/uploads/Difficult-Parent-or-Traumatised-Parent-CYPF-December-2023_FINALS-TO-PRESS_SP-2-Difficult-parent.pdf

Griffin, J., Finch, E., Yakeley, M., Bonger, N., Villierezz, P., & O’Dwyer, S. (2024). Parent carer trauma: A discussion paper on trauma and parents of children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities Affinity Hub. London, UK: Affinity Hub. affinityhub.uk https://www.affinityhub.uk/wp-content/uploads/PARENT-CARER-TRAUMA-Discussion-Paper-FINAL-May-2024.pdf

Hall, C., & Slembrouck, S. (2009). Communication with parents in child welfare: Skills, language and interaction. Child and Family Social Work, 14(4), 461–470. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2009.00629.x

Harris, M., & Fallot, R. D. (2001). Envisioning a trauma‐informed service system: A vital paradigm shift. New Directions for Mental Health Services, 89(Spring), 3–22. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.23320018903 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11291260

Herman, J. L. (1997). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence-from domestic abuse to political terror. New York, USA: Basic Books.

Hesse-Biber, S., Rodriguez, D., & Frost, N. (2015). A quality driven approach to multimethod and mixed methods research. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. Johnson (Eds). The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry. (pp. 3–20). New York, USA: Oxford University Press. research.ebsco.com https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=015ad6eb-21db-3338-a430-8f6345ac5653

Holmes, C., Zeleke, W., Sampath, S., & Kimbrough, T. (2024). “Hanging on by a thread”: The lived experience of parents of children with medical complexity. Children, 11(10), 1258. DOI https://doi.org/10.3390/children11101258 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39457223

Hopper, E., Bassuk, E., & Olivet, J. (2010). Shelter from the storm: Trauma-informed care in homelessness services settings. The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 3(1), 80–100. DOI https://doi.org/10.2174/1874924001003010080

Horsell, C. (2023). Problematising disability: A critical policy analysis of the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme. Australian Social Work, 76(1), 47–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2020.1784969

Johnstone, L., & Boyle, M. (2018). The power threat meaning framework: An alternative nondiagnostic conceptual system. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 65(4), 800–817. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167818793289

Keenan, B. M., Newman, L. K., Gray, K. M., & Rinehart, N. J. (2016). Parents of children with ASD experience more psychological distress, parenting stress, and attachment-related anxiety. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 2979–2991. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2836-z PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27312716

Keesler, J. M., Samways, B., & McNally, P. (2025). Trauma-informed care training: A systemwide process to transform the act of caring. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Multidisciplinary Research and Practice Across the Lifespan, 9, 494–506. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-025-00449-x

Kezelman, C., & Stavropoulos, P. (2020). Organisational guidelines for trauma-informed service delivery. Sydney, Australia: Blue Knot Foundation. blueknot.org.au https://blueknot.org.au/product/organisational-guidelines-for-trauma-informed-service-delivery-digital-download/

Krippendorff, K. (2019). The logic of content analysis designs. In K. Krippendorff (Ed). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE. DOI https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781.n5

Lenain, C., & Lever Taylor, B. (2023). A qualitative exploration of parenting representations amongst mothers with young children on the edge of care. Child and Family Social Work, 28(3), 600–611. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12987

Menschner, C., & Maul, A. (2016). Key ingredients for successful trauma-informed care implementation. Hamilton, NJ, USA: Center for Health Care Strategies. chcs.org https://www.chcs.org/resource/key-ingredients-for-successful-trauma-informed-care-implementation/

Merritt, D. H. (2020). How do families experience and interact with CPS? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 692(1), 203–226. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716220979520 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38075400

National Disability Insurance Agency. (2018). Improved NDIS planning for people with complex support needs. Geelong, Australia: National Disability Insurance Agency. ndis.gov.au https://www.ndis.gov.au/news/1002-improved-ndis-planning-people-complex-support-needs

National Disability Insurance Agency. (2023). History of the NDIS. Geelong, Australia: National Disability Insurance Agency. ndis.gov.au https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/history-ndis

Olney, S., & Dickinson, H. (2019). Australia's new National Disability Insurance Scheme: Implications for policy and practice. Policy Design and Practice, 2(3), 275–290. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2019.1586083

Piotrowski, C. (2019). ACEs and trauma-informed care. In G. J. Asmundson & T. O. Afifi (Eds). Adverse childhood experiences: Using evidence to advance research, practice, policy, and prevention. (pp. 307–328). San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816065-7.00015-X

Productivity Commission. (2011). Disability care and support. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government. pc.gov.au https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries-and-research/disability-support/report

Scanlon, F., Farrelly-Rosch, A., & Nicoll, H. (2018). Clinical practice in youth mental health: What is trauma-informed care and how is it implemented in youth healthcare settings? Parkville, Australia: Orygen. orygen.org.au https://www.orygen.org.au/Training/Resources/Trauma/Clinical-practice-points/What-is-trauma-informed-care-and-how-is-it-impleme

Silburn, K., & Lewis, V. (2020). Commissioning for health and community sector reform: Perspectives on change from Victoria. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 26(4), 332–337. DOI https://doi.org/10.1071/PY20011 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32654686

Spaan, N., Van Trigt, P., & Schippers, A. (2024). Integration of a disability lens as prerequisite for inclusive higher education. European Journal of Inclusive Education, 3(1), 1–24. DOI https://doi.org/10.7146/ejie.v3i1.137271

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2015). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. store.samhsa.gov https://store.samhsa.gov/product/trauma-informed-care-behavioral-health-services/sma15-4420

Thill, C. (2015). Listening for policy change: How the voices of disabled people shaped Australia's National Disability Insurance Scheme. Disability and Society, 30(1), 15–28. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2014.987220

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. DOI https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17872937

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 15, 398–405. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23480423

Van Nieuwenhove, K., & Meganck, R. (2019). Interpersonal features in complex trauma etiology, consequences, and treatment: A literature review. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 28(8), 903–928. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1405316

Versace, V. L., Skinner, T. C., Bourke, L., Harvey, P., & Barnett, T. (2021). National analysis of the Modified Monash Model, population distribution and a socio‐economic index to inform rural health workforce planning. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 29(5), 801–810. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12805 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34672057

Victorian State Government. (2022). Inclusive Victoria: State disability plan 2022–2026. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian State Government. vic.gov.au https://www.vic.gov.au/state-disability-plan

Victorian State Government. (2025). Website. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian State Government. vic.gov.au https://www.vic.gov.au

Appendix I

COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research) checklist

Developed from Tong et al. (2007)

| Topic | Item no. | Guide questions/description | Reported on page no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Research team and reflexivity | |||

|

Personal characteristics |

|||

|

Interviewer/facilitator |

1 |

Which author/s conducted the interview or focus group? |

Data collection |

|

Credentials |

2 |

What were the researcher’s credentials? e.g. PhD, MD |

Reflexivity statement; Author profiles |

|

Occupation |

3 |

What was their occupation at the time of the study? |

Reflexivity statement; Author profiles |

|

Gender |

4 |

Was the researcher male or female? |

Reflexivity statement; Author profiles |

|

Experience and training |

5 |

What experience or training did the researcher have? |

Reflexivity statement; Author profiles |

|

Relationship with participants |

|||

|

Relationship established |

6 |

Was a relationship established prior to study commencement? |

Program description and context; Participant recruitment |

|

Participant knowledge of the interviewer |

7 |

What did the participants know about the researcher? e.g. personal goals, reasons for doing the research |

Program description and context; Participant recruitment |

|

Interviewer characteristics |

8 |

What characteristics were reported about the inter viewer/facilitator? e.g. Bias, assumptions, reasons and interests in the research topic |

Participant recruitment; Limitations; Reflexivity statement |

| Domain 2: Study design | |||

|

Theoretical framework |

|||

|

Methodological orientation and Theory |

9 |

What methodological orientation was stated to underpin the study? e.g. grounded theory, discourse analysis, ethnography, phenomenology, content analysis |

Methods |

|

Participant selection |

|||

|

Sampling |

10 |

How were participants selected? e.g. purposive, convenience, consecutive, snowball |

Participant recruitment |

|

Method of approach |

11 |

How were participants approached? e.g. face-to-face, telephone, mail, email |

Participant recruitment |

|

Sample size |

12 |

How many participants were in the study? |

Findings |

|

Non-participation |

13 |

How many people refused to participate or dropped out? Reasons? |

N/A |

|

Setting |

|||

|

Setting of data collection |

14 |

Where were the data collected? e.g. home, clinic, workplace |

Data collection |

|

Presence of non-participants |

15 |

Was anyone else present besides the participants and researchers? |

Data collection |

|

Description of sample |

16 |

What are the important characteristics of the sample? e.g. demographic data, date |

Findings |

|

Data collection |

|||

|

Interview guide |

17 |

Were questions, prompts, guides provided by the authors? Was it pilot tested? |

Appendix III |

|

Repeat interviews |

18 |

Were repeat interviews carried out? If yes, how many? |

N/A |

|

Audio/visual recording |

19 |

Did the research use audio or visual recording to collect the data? |

Data collection |

|

Field notes |

20 |

Were %uFB01eld notes made during and/or after the interview or focus group? |

N/A |

|

Duration |

21 |

What was the duration of the interviews or focus group? |

N/A |

|

Data saturation |

22 |

Was data saturation discussed? |

N/A |

|

Transcripts returned |

23 |

Were transcripts returned to participants for comment and/or correction? |

N/A |

| Domain 3: analysis and findings | |||

|

Data analysis |

|||

|

Number of data coders |

24 |

How many data coders coded the data? |

Data analysis |

|

Description of the coding tree |

25 |

Did authors provide a description of the coding tree? |

Table 1; Figure 3 |

|

Derivation of themes |

26 |

Were themes identified in advance or derived from the data? |

Table 1; Figure 3 |

|

Software |

27 |

What software, if applicable, was used to manage the data? |

N/A |

|

Participant checking |

28 |

Did participants provide feedback on the findings? |

N/A |

|

Reporting |

|||

|

Quotations presented |

29 |

Were participant quotations presented to illustrate the themes/findings? Was each quotation identified? e.g. participant number |

Findings |

|

Data and findings consistent |

30 |

Was there consistency between the data presented and the findings? |

Findings |

|

Clarity of major themes |

31 |

Were major themes clearly presented in the findings? |

Findings |

|

Clarity of minor themes |

32 |

Is there a description of diverse cases or discussion of minor themes? |

Limitations |

Appendix II

Details about policy, legislative, system and contextual influences on the program model

| Contexts | Key points |

|---|---|

| Global |

Australia is a signatory on key United Nations conventions, namely: United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd), and United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (https://www.unicef.org.au/united-nations-convention-on-the-rights-of-the-child). |

| Nationwide disability reform agenda |

The disability reform environment seeks to challenge the dehumanisation of people with a disability as objects of intervention, elevate the experiential knowledge and voices of this group and their carers, and stop the stereotyping and systematic marginalisation occurring at all levels of decision making about their lives (Horsell, 2023; Olney & Dickinson, 2019; Thill, 2015). A reform goal was to move from block (government) funding to individualised funding for self-directed care, to increase equity and provide a personalised model of disability support and care (Olney & Dickinson, 2019). |

| National policy environment |

The Australian Productivity Commission inquiry in Disability Care and Support 2009 sought public submissions; consultations were extensive, involving 1,100 submissions from people with disabilities, carers, service providers, governments and business (). The current system problems of overlapping federal and state arrangements, as identified by the Productivity Commission inquiry, were inequitable, underfunded, fragmented and inefficient. People with disabilities and their families are disempowered and have little choice. Families and carers are devalued. There is insufficient engagement with the community. People have no confidence about the future, or what services will and will not be available (Productivity Commission, 2011). |

| National strategies |

Australia’s Disability Strategy 2021–2031 is a national framework that all Australian governments have signed up to. It sets out a plan for continuing to improve the lives of people with disability in Australia over 10 years. The Strategy is based on the social model of disability. It recognises attitudes, practices and structures can be disabling and act as barriers (https://www.dss.gov.au/australias-disability-strategy). |

| National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) |

The NDIS aims to increase funding and access to services, and support and increase control that people with disabilities have over the design and delivery of their care (National Disability Insurance Agency, 2023). It is framed as having a rights-based focus on service planning, providing more autonomy (‘choice and control’) for people with disabilities (Horsell, 2023; Olney & Dickinson, 2019). |

| National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) |

The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) is an independent statutory agency, responsible for the implementation of the NDIS (National Disability Insurance Agency, 2018). An Independent Advisory Council (IAC), representing the voices of participants and advises the NDIA about the issues affecting participants, carers and families (National Disability Insurance Agency, 2018). |

| State government environment |

The Victorian State Government operates as a large and complex system, some departments include Education, Health, Justice and Families, Fairness and Housing (Victorian State Government, 2025). As a public entity, this includes a responsibility for the NDIS and disability services and support in Victoria. An important primary legislative area of the state is The Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006. This is an Act of Parliament of the State of Victoria, Australia, designed to protect and promote human rights. It protects 21 fundamental human rights; for example, the right to take part in public life (Victorian State Government, 2025). Another important piece is the State Disability Plan 2022–2026. It outlines goals for six systemic reform areas to make things fairer for people with disability. |

| Government Department of Program origin |