Article type: Report

14 May 2025

Volume 47 Issue 1

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 23 October 2024

REVISED: 7 May 2025

ACCEPTED: 8 May 2025

Article type: Report

14 May 2025

Volume 47 Issue 1

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 23 October 2024

REVISED: 7 May 2025

ACCEPTED: 8 May 2025

![]() Bridging the gap: Social work practice challenges in navigating support for families with disabilities

Bridging the gap: Social work practice challenges in navigating support for families with disabilities

Affiliations

1 FamilyCare, Shepparton, Vic. 3630, Australia

2 FamilyCare, Cobram, Vic. 3643, Australia

3 FamilyCare, Seymour, Vic. 3661, Australia

Correspondence

*Ms Susan P Caines

Contributions

Susan P. Caines - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Janet Congues - Study conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Liza Costigan - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Critical revision

Neeska Robinson - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Critical revision

Carolyn Grace - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Critical revision

Liz Franklin - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Critical revision

Ally Argus - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Critical revision

Susan P. Caines1 *

Janet Congues1

Liza Costigan1

Neeska Robinson2

Carolyn Grace3

Liz Franklin3

Ally Argus1

Affiliations

1 FamilyCare, Shepparton, Vic. 3630, Australia

2 FamilyCare, Cobram, Vic. 3643, Australia

3 FamilyCare, Seymour, Vic. 3661, Australia

Correspondence

*Ms Susan P Caines

CITATION: Caines, S. P., Congues, J., Costigan, L., Robinson, N., Grace, C., Franklin, L., & Argus, A. (2025). Bridging the gap: Social work practice challenges in navigating support for families with disabilities. Children Australia, 47(1), 3043. doi.org/10.61605/cha_3043

© 2025 Caines, S. P., Congues, J., Costigan, L., Robinson, N., Grace, C., Franklin, L., & Argus, A. This work is licensed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Abstract

The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) has transformed the landscape of disability support in Australia, yet significant gaps remain, particularly for families in rural areas who have members requiring assistance but are yet to access NDIS packages. This paper explores reflections from five regional social workers about the challenges they faced supporting such families. Thematic analysis of the discussions was used to identify the invisible nature of working with families who require disability services but are yet to engage with the NDIS. Further research is required to better understand what is happening for services and their families who fall outside NDIS-funded services.

Keywords:

disability, family services, NDIS, rural, social work.

Background

Many countries around the world utilise disability insurance schemes to improve access to services and increase support for people with disabilities based on their individual needs (Collings et al., 2016; Malbon et al., 2019; McGuigan et al., 2016) . Since the introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in Australia, it has become evident there is a significant gap for social workers providing services to families who have one or more members who ultimately require NDIS support. This gap relates to the service provision available to families in which members (including adults, teenagers and children) have a diagnosis or are yet to receive a specific diagnosis for their disability and do not have access to an NDIS package (Boaden et al., 2021; Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare, 2024; Gavidia-Payne, 2020; Russo et al., 2021). It also includes people who have what is often referred to as an ‘invisible’ disability, such as those who are considered neurodivergent, and therefore struggle to access disability support services. This paper explores the reflections of five rural social workers who have encountered such challenges when working with families who need to access disability support services but are engaged in programs that fall outside that remit.

Much of the literature relating to the NDIS and disability support services tends to focus on the effectiveness of implementation, the ability of the market to meet demand and the capacity of service providers to adjust and transition from a block-funding model to an individualised fee-for-service model (Boaden et al., 2021; Quilliam & Bourke, 2020; Spivakovsky, 2021). At the same time, some studies also recognise the disparity between those living in metropolitan centres and people with a disability living in rural areas (Cullenward et al., 2024; Malbon et al., 2019; Quilliam & Bourke, 2020). This disparity relates to the impact smaller populations have on the competitive market when there are minimal choices for service options, and a less dense population demand for services that results in delayed timeframes in accessing required appointments (Malbon et al., 2019; Quilliam & Bourke, 2020). In particular, missing from the research on the impact of NDIS implementation in regional areas is what happens to families in which there are one or more family members requiring disability support but families can only access non-disability-specific support services (Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare, 2024; Spivakovsky, 2021). This paper therefore explores some of the challenges social workers working in a rural service faced working with adults, teenagers and children while trying to access provisions for appropriate diagnostic steps and subsequent application to NDIS within their current programs.

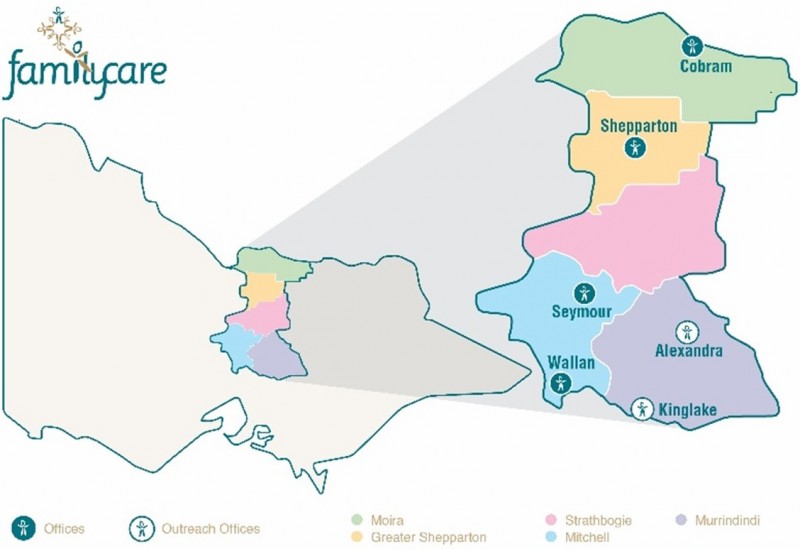

The discussions that informed this paper drew on the experiences of practitioners working at FamilyCare across central Victoria, Australia (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The area in regional Victoria where the practitioners worked.

The staff contributing to the writing of this paper provided reflective insight into some of the challenges they encountered and actions they took. They wanted to highlight the impact the NDIS had on their ability to support families to become strong and stable family units when there were difficulties accessing disability services without an NDIS package.

How the paper came about

The voice of practitioners is posited as expert to ensure that their experience and expertise is used to identify perceived gaps in the quality of services provided when they encounter families who require access to the NDIS (Brooks, 2007; Gurung, 2020; Ratna et al., 2023). The five practitioners who came together with their Team Leader to discuss these challenges are currently employed at FamilyCare. Of the five, one had avoided being involved in the disability sector at all, two had been exposed via their current role and two had worked in the disability sector prior to the NDIS coming into effect. All, however, have extensive knowledge and experience in the broader community services sector. The Team Leader has extensive social work experience and oversees the operational guidelines of the agency’s disability support services. This paper reflects on our workplace practices and aligns with this agency’s continuous quality improvement policies about identifying opportunities to strengthen gaps in service provision.

This paper arose out of numerous informal conversations held between participating staff and the lead author of this paper. These conversations led to the group agreeing to formalise and record their discussions as evidence for the co-authorship of this paper. These recordings were transcribed using Microsoft 365 recording and transcribing applications. They are stored in the agency’s secure SharePoint site and access is password protected and limited to the authors involved in the project. When analysing the transcripts, statements that stood out as significant were highlighted and then transferred to a question matrix that is used in the agency when conducting internal audit interviews. This approach allowed the authors to review all of the quotes, and it was at this point that we identified the thematic patterns that arose from the formalised conversations. No ethics approval was sought or required because this paper is written as part of the social workers’ reflective practices.

Practice challenges

Three specific themes were identified from the conversations. They were:

- Navigating the NDIS;

- Navigating NDIS outcomes; and

- Additional skill sets required.

These themes identify the level of work staff applied to ensure that the families they encountered that required support to access the NDIS were appropriately supported, despite the lack of funding available for such actions.

Navigating the NDIS

The most significant finding was that there are no easily accessible guidelines for navigating the NDIS application process. As one practitioner commented, they had ‘no idea, from start to finish’ (P1) about what was required to support their clients to attain an NDIS package. As workers gained experience in supporting families to access an NDIS package, navigating application requirements became easier

because I’ve now had the experience of working with several clients on NDIS. (P2)

For another, the level of difficulty navigating the NDIS depended on

whether they’re already on a package or they’re not on a package. If they own a package … I do not understand the packages at all. (P4)

The ability to navigate NDIS requirements clearly develops the more practitioners are exposed to the system, even though it can be daunting in the beginning.

When reflecting on navigating the NDIS requirements for access to packages, the practitioners’ discourse included words like ‘tricky’, ‘difficult’, ‘hard’ and ‘frustrating’ to describe their experiences. This was particularly highlighted by one practitioner, who stated that

what works one time you do it [does not] the next time … So, there's no hard and fast rule when it comes to this scheme. (P3)

Practitioners often end up in a position where they must know

how to diagnose where to go, and [how to] support all that sort of stuff. (P1)

One practitioner surmised how

frustrating for the clients that we are not ‘the experts’ they anticipated being referred to. (P4)

With no easily identifiable process to follow, it was difficult

… chasing around trying to get answers, or you know, you’ll email someone and [have to] wait for a response. (P1)

This suggests that there is a communication challenge in how the NDIS informs the broader human services sector of its processes, especially when there are changes.

Engaging and communicating with NDIS professionals also has its challenges. Many of the families engaged with family services, are there because they have been identified or reached out for support to address specific challenges they face, within their family unit. When this includes family members who have a disability where they would benefit from accessing an NDIS package, communication between professionals becomes pivotal to the family achieving their best possible outcome (Boaden et al., 2021; Gavidia-Payne, 2020). As one practitioner commented,

I’m not ashamed to say some of those services are disgraceful – like don’t reply, don’t get back to you. (P1)

This lack of response undermines the level of trust practitioners have in achieving a quality outcome for their clients because

if this is how they respond to me as a professional … imagine the [clients] that are trying to reach out for the support and not getting anything back! (P1)

Further, when they uncover the level of evidence required to support a client’s application it was found that

gathering information has been really tricky. (P5)

This is due to gaining eligibility for a package being

one of the most challenging components. (P3)

Practitioners also noted that, in their experience, prior to the introduction of the NDIS, people with an IQ under 70,

under the old system, would have been supported by DHHS or DFFH [but now are] not eligible for NDIS. (P3)

In the past, there were a range of programs they could access,

now all they’ve got is us (P3)

and this program, Integrated Family Services, is for 12 months. Further, there have been times when

documents … got lost once it got to the [NDIS] office and they were signed letters from the paediatrician. [Such letters] are so hard to come by and they misplaced them on their end. (P1)

Clearly, such challenges place an extra burden on practitioners that has them working outside of their areas of expertise.

Navigating outcomes

Aside from the challenges practitioners face supporting their clients through the NDIS application process, there are ongoing ‘frustrations’ associated with navigating outcomes. There are times when the package provided to the client

doesn’t meet the needs of the client [and subsequently, a review is required. In one case] the mum wants me to participate in that and also advocate … but there’s apparently a backlog in review meetings so the request was made many weeks ago, but we still haven’t had the review meeting. (P2)

As such, the child in this case, who required the review to assess if they could get the support they need, was left in limbo, waiting not only for the review but also for the outcome. For this child, the time taken navigating the NDIS to ensure the package would meet their needs impeded on their ability to ‘attend […] education’ (P2). This case provides a clear example of how navigating NDIS access and application outcomes eats into the time family service workers have to work with families on other issues (Boaden et al., 2021; Gavidia-Payne, 2020).

Navigating NDIS outcomes with clients to ensure their needs are met when they do have a package also

takes a big wad out of our service hours with those clients. (P4)

This is because when families

finally get to a point where a package is allocated, it doesn’t mean they get what they need … [because] you’re just on wait lists [for accessing appropriate services]. (P3)

As another practitioner stated,

there just seems to be a lack of experience and really skilled support workers (P2)

as well as a limited access to service providers more broadly in rural and regional areas.

Further, the NDIS outcomes often fail to address practicalities associated with people having to travel between country towns to attend appointments. In one example, a single mother of five needed to

catch a bus with two littlies to get to an appointment in Shepparton, which is two hours (P5)

all within school hours because that is where her other three children were. The practitioners spoke about how they must advocate, at times, on behalf of clients because the NDIS system does not always account for the geographic challenges many rural and regional families contend with.

Additional skills required

Most of the practitioners identified the

additional demand of work on the [family services] workers [and how] we’ve been lumped with the expectation of additional skill sets that just aren’t there. (P3)

They spoke of spending

so much time chasing around to get answers, so much more involved (P2) [and how the role has] expanded beyond what it used to be. (P3)

Navigating the NDIS has such ‘a big impact’ (P5) on the workload of the practitioners, who have to be prepared

… to jump through all these hoops to learn and understand how to navigate the NDIS and then work with their clients so they too can understand the process and then if they do receive the package they can actually use the funding that they’ve been given. (P4)

While many of the findings so far relate to the challenges practitioners face working with families who have one or more members with a disability, they also identified the additional skills required to ensure that the needs of families are met. As one practitioner described, navigating the NDIS was

like teaching me a new language because I’m so foreign to it. (P1)

She suggested a

101 for Dummies – cause in this space, I really am! (P1)

Significantly, most practitioners identified the ‘huge impact’ (P1) the NDIS has on their time and the time of the person they reach out to for help because

someone else is going to take the time to talk through it with me. (P1)

Another practitioner had to

take a day … to do an online full day course just on information. (P5)

Implications for practice

As evidenced by the above findings, we have found that for practitioners working outside of the disability sector, there are significant challenges that include:

- Social workers in family support services are already very busy in their primary aim of supporting families and navigating the NDIS is a significant time and resource burden;

- A lack of easily accessible guidelines for navigating the NDIS application process for family support service staff;

- A lack of communication between NDIS and broader family services sector, especially when there are changes;

- Difficulty for family services practitioners in supporting families to identify the appropriate disability services because this is outside their primary expertise;

- Disability services not responding to family support services staff, losing documents and/or having long waitlists; and

- Disability support services spread thinly over large geographic areas, making access particularly difficult for people living in regional and rural locations.

Institutional bodies, for example governments, implementing schemes like the NDIS need to consider and provide practical ways in which families can be better supported and resourced to ensure that they are able to access services while awaiting formal diagnosis and undergoing NDIS package application processes. Further, this paper suggests that future research is required to enhance how this can be best accomplished.

Acknowledgements

We thank FamilyCare for the encouragement to pursue this strategy for engaging in policy and practice debates.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

Boaden, N., Purcal, C., Fisher, K., & Meltzer, A. (2021). Transition experience of families with young children in the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). Australian Social Work, 74(3), 294–306. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2020.1832549

Brooks, A. (2007). Feminist standpoint epistemology: Building knowledge and empowerment through women’s lived experience. In S. N. Hesse-Biber & P. L. Leavy (Eds). Feminist research practice. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications. DOI https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984270

Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare. (2024). Summary report for the CFS disability survey. Melbourne: Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare.

Collings, S., Dew, A., & Dowse, L. (2016). Support planning with people with intellectual disability and complex support needs in the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 41(3), 272–276. DOI https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2016.1151864

Cullenward, J., Hall, L., Cook, A., Ambler, D., Cleary, B., Smith, T., & Thomas, M. (2024). Key success factors in implementing allied health outreach services. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 32(5), 1072–1075. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.13183 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39305163

Gavidia-Payne, S. (2020). Implementation of Australia's National Disability Insurance Scheme: Experiences of families of young children with disabilities. Infants and Young Children, 33(3), 184–194. DOI https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0000000000000169

Gurung, L. (2020). Feminist standpoint theory: Conceptualization and utility. Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 14, 106–115. DOI https://doi.org/10.3126/dsaj.v14i0.27357

Malbon, E., Alexander, D., Carey, G., Reeders, D., Green, C., Dickinson, H., & Kavanagh, A. (2019). Adapting to a marketised system: Network analysis of a personalisation scheme in early implementation. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27, 191–198. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12639 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30151934

McGuigan, K., McDermott, L., Magowan, C., McCorkell, G., Witherow, A., & Coates, V. (2016). The impact of direct payments on service users requiring care and support at home. Practice, 28(1), 37–54. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2015.1039973

Quilliam, C., & Bourke, L. (2020). Rural Victorian service provider responses to the National Disability Insurance Scheme. The Australian Journal of Social Issues, 55(4), 439–455. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.107

Ratna, H., Kathiresan, L., & Priyanka, P. (2023). Feminist standpoint theory and its importance in feminist research. Journal of Social Work Education and Practice, 5(2), 46–55. google.com https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.jswep.in/index.php/jswep/article/download/99/96&ved=2ahUKEwiblsyd6p6NAxU0zTgGHRXWLsEQFnoECBkQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3EV_dzbNSjlJS0_QS_bpYA

Russo, F., Brownlow, C., & Machin, T. (2021). Parental experiences of engaging with the National Disability Insurance Scheme for their children: A systematic literature review. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 32(2), 67–75. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207320943607

Spivakovsky, C. (2021). Barriers to the NDIS for people with intellectual disability and/or complex support needs involved with the criminal justice systems: The current state of literature. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 46(4), 329–339. DOI https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2020.1855695 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39818605