Article type: Research Methods and Reporting

20 December 2024

Volume 46 Issue 2

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 9 August 2024

REVISED: 19 November 2024

ACCEPTED: 26 November 2024

Article type: Research Methods and Reporting

20 December 2024

Volume 46 Issue 2

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 9 August 2024

REVISED: 19 November 2024

ACCEPTED: 26 November 2024

![]() Developing Minimum Practice Standards for specialist and community support services responding to child sexual abuse

Developing Minimum Practice Standards for specialist and community support services responding to child sexual abuse

Affiliations

1 Australian Centre for Child Protection, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia

2 Brightwater Care Group, Perth, WA, Australia

3 yamagigu Consulting, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Correspondence

*Mrs Amanda J Paton

Contributions

Amanda J Paton - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Victoria Parsons - Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Critical revision

Kim Adamson - Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data

Claudia Pitts - Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data

Leah Bromfield - Study conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data

Gina Horch - Acquisition of data

Amanda J Paton1 *

Victoria Parsons1

Kim Adamson2

Claudia Pitts3

Leah Bromfield1

Gina Horch1

Affiliations

1 Australian Centre for Child Protection, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia

2 Brightwater Care Group, Perth, WA, Australia

3 yamagigu Consulting, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Correspondence

*Mrs Amanda J Paton

CITATION: Paton, A. J., Parsons, V., Adamson, K., Pitts, C., Bromfield, L., & Horch, G. (2024). Developing Minimum Practice Standards for specialist and community support services responding to child sexual abuse. Children Australia, 46(2), 3027. doi.org/10.61605/cha_3027

© 2024 Paton, A. J., Parsons, V., Adamson, K., Pitts, C., Bromfield, L., & Horch, G. This work is licensed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Abstract

More than one in three females and almost one in five males will experience child sexual abuse in Australia. Despite a recognised need to strive for consistent, safe and effective services that respond to child sexual abuse, there are currently no agreed minimum practice standards to guide services and victim–survivors to make informed choices about responses they provide or receive. The aim of this program was to develop Minimum Practice Standards for Specialist and Community Support Services Responding to Child Sexual Abuse (the Standards) that were evidence informed and accepted by the sector, victim–survivors and government. The design of the Standards utilised an evidence-informed mixed-methods approach and included a literature review, multiple rounds of consultation and validation and final government endorsement. This included parallel streams of focus groups, expert advisory discussions, validation processes and surveys, and consolidation of written feedback. Consultation across the community support and specialist child sexual abuse sector included: those with a lived experience; key stakeholders from the community services sector; key stakeholders – government, peak bodies, advisory groups and other interested parties; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; and academic, practice and policy experts. Through multiple cycles of iterative consultations, revisions and validation, the Standards achieved a high level of consistency and consensus on acceptability measures and received full government endorsement. The findings suggest that there will be challenges with implementing these Standards but this also reflects that change is needed across the community support and specialist child sexual abuse sector to ensure minimum standards of safe and effective care for victims and survivors of child sexual abuse. The Standards provide an important tool for critical service-, organisation- and systems-level change to occur.

Keywords:

co-design, child sexual abuse, consultation, standards, victim–survivors.

Introduction

The prevalence of child sexual abuse is a pervasive global issue, and Australia is no exception (Mathews et al., 2023; Stoltenborgh et al. 2011). More than one in three females and almost one in five males will experience child sexual abuse in Australia, with more than three quarters of these involving multiple incidents (Mathews et al., 2023). The enormity of the problem is displayed in the profound and often long-term impacts on victims and survivors of child sexual abuse as well as their families and the broader community (Fong et al., 2020; Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, 2017a; Ruiz, 2016; Scott et al., 2023;). Impacts are often complex, permeate all areas of a person’s life and can result in trauma. Trauma is the psychological, physical, social, emotional, cultural and/or spiritual harm caused by exposure to an event, or series of events, that are life-threatening or emotionally disturbing (Paton et al., 2023).

Evidence suggests that trauma-informed care can reduce the effects of traumatic experiences and avoid or reduce harmful practices that can impede recovery or re-traumatise victims and survivors (Duffee et al., 2021; Quadara & Hunter, 2016; Saunders et al., 2023). The principles of trauma-informed care include safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration and empowerment. A core tenet of the principles of trauma-informed care is the need for organisational and systems-level change in policies, funding models and practices to ensure that individuals can work in accordance with the principles (Duffee et al. 2021; Quadara & Hunter, 2016). However, the implementation of trauma-informed care across systems, services and jurisdictions has been found to be inconsistent and lacking the inclusion of lived experience perspectives in a meaningful way (Duffee et al. 2021).

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Royal Commission) found that many victims and survivors faced systemic and structural barriers, with mainstream services lacking relevant knowledge, specialist services lacking capacity and an overall lack of cultural competency and awareness of diverse abilities (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, 2017b). Accessibility of services for victims and survivors was particularly challenging in regional and remote areas; however, complex needs, stigma and structural barriers were found to make accessibility a challenge for most victims and survivors (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, 2017b). Understanding that child sexual abuse affects many areas of a person’s life highlights the need for mainstream services to understand the impacts on victims and survivors and improve trauma-informed responses to avoid re-traumatisation (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, 2017b).

Across Australia, there are a range of early intervention, secondary and tertiary services within specialist and general or community-based service settings that respond to child sexual abuse. Specialist services are defined by the Royal Commission (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, 2017b, p. 106) as:

... those whose core focus is addressing the impacts of sexual assault or child sexual abuse. Specialist sexual assault services provide free and confidential information, medical treatment and forensic examinations, crisis and ongoing counselling and support, and court support for victims of sexual assault as well as non-offending family members, carers, and friends (p. 106).

Specialist services work with people who have experienced child sexual abuse at any age across the lifespan and within different populations. Community support services differ in that they:

cover a broad range of services that assist individuals and groups who are experiencing crisis or persistent hardship, with the aim of building their capacity and resilience (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, 2017b, p.105).

Community support services work with targeted at-risk populations across a range of areas and respond to groups of individuals who have experienced an adverse situation, experience or condition. Whilst those individuals who have experienced, or are at risk of experiencing, child sexual abuse may also access these services, the focus is not on responding to child sexual abuse. These services include accommodation services, community drug and alcohol services, legal support services, peer support, parenting support services and community health networks. The Royal Commission highlighted the need to improve service systems for victims and survivors and provide a holistic and cohesive systems response (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, 2017b). With child sexual abuse impacting such large numbers of children, and our growing awareness of the often devastating and lifelong impact of these experiences on the individual, family and community, our attention naturally turns to adequacy of our service system responses (Cashmore & Shackel, 2013; Fong et al., 2017; Scott et al., 2023).

Despite a recognised need and desire across Australia to strive for implementing services and approaches that respond appropriately and ameliorate the harmful impacts of child sexual abuse, prior to the Standards being published in 2023 there had been no agreed upon consistent approach, intervention or model recognised as a ‘gold standard’. In fact, there had been no current agreed upon practice standards, or minimum benchmarks, that would guide services and victim and survivors to make informed choices about responses they provide or receive. The development of a minimum expectation of services in responding to child sexual abuse was necessary to promote safe and effective service provision and to guide service providers, victims and survivors and their supporters.

In response to the Royal Commission’s recommendations, under the National Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Child Sexual Abuse 2021–2030 (National Office for Child Safety (NOCS), 2021), the National Office for Child Safety sought to address this gap by commissioning a baseline analysis of specialist and community support services (the sector) responding to child sexual abuse, including the development of a set of minimum practice standards. Therefore, the aim of this program of work was to develop a set of Minimum Practice Standards for Specialist and Community Support Services Responding to Child Sexual Abuse across Australia (the Standards), which could then be used as a baseline measure for the sector. The Standards were intended to be applied within various contexts, locations and across service types (specialist and community support), for users of child sexual abuse services from varying priority groups, including: victims and survivors of child sexual abuse and their advocates; children and young people and their advocates; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; culturally and linguistically diverse communities; people with disability; people who identify as LGBTQIA+; and people living in regional and remote communities. Whilst the initial focus was on development of the Standards for use in the baseline analysis, the longer-term goal was for the Standards to influence and enhance service design, delivery and outcomes for victims and survivors across Australia.

A mixed-methods evidence-informed practice approach was used to design, refine and validate the Standards. The evidence-informed practice approach integrates expertise from practitioners and people with lived experience alongside research evidence, which can reduce bias and improve design at the individual, service and organisation levels (Alla & Joss, 2021). A focus during the design process was also to consider early implementation barriers and facilitators. The need for early adoption of trauma-informed, victim and survivor-centred and culturally safe services was critical. This program of work utilised an iterative process to bring together the knowledge and views from the literature, expert advisors, the sector (inclusive of government, community-controlled organisations and Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations), those with a lived experience and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, and involved several phases of development, consultation, refinement and validation.

This article describes the consultative process and integration of multiple perspectives in developing the Standards, from the initial literature review through to the endorsed Standards. The inclusion of validation and iterative refinement throughout is discussed as significantly contributing to the likely implementation success of the Standards and therefore supporting improved practices when working with victims and survivors of child sexual abuse.

Methods

The development of the Standards utilised an evidence-informed mixed-methods approach equally incorporating research evidence, the voice and views of those with a lived experience of child sexual abuse, practice expertise and sector knowledge. Following the model of an evidence-informed approach by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS: Alla & Joss, 2021), this process spanned 12 months, included a literature review, multiple rounds of consultation, validation and final government endorsement. A Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach was undertaken in line with the principles of PAR, which include collaboration, participation, power of knowledge and social change (AIFS, 2015). Individuals participated within their professional roles as a key group of stakeholders that would be affected by the Standards. The process allowed for collaborative and collective learning between sector participants, the research team and community participants through the iterative process of refining and validating the Standards (Okoko, 2023).

Although no ethics approval was sought, given the primary focus was on consulting with the service sector to which the Standards were to apply (i.e. the specialist and community support sector responding to child sexual abuse) to design the Standards, all procedures were aligned with national and institutional ethical guidelines (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2020; National Health and Medical Research Council et al., 2018). Participants who contributed to sector consultations were practice experts who, in their professional roles, had knowledge and experience of child sexual abuse and the service system for which the Standards were being designed. Those engaged in providing input within the lived experience community of practice group were part of an established network–advisory group and were supported to provide input within the pre-existing structures and supports of that group. Likewise, an Aboriginal-owned consulting group was engaged to ensure culturally appropriate consultations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. An Aboriginal researcher and practitioner was also included in the expert advisory group to ensure Indigenous Leadership informed the refinement of the Standards.

Principles of informed consent were used for all data collection methods and included information about purpose, data usage and storage, recording and storage of materials from workshops, choice and ability to withdraw at any time.

As depicted in Table 1, the process began with generation of themes drawn from the literature and initial exploration with an Expert Advisory Group and Lived Experience Community of Practice group. These themes were transformed into draft standards via significant sector and priority population consultation and then refined via further consultation, validation and testing to develop the final Standards, which were later endorsed by state and federal governments.

Influence of researcher positionality

The research team comprised research academics, practitioners and cultural advisors, each with their own intersecting identities and professional and personal experiences relevant to the development of the Standards. These identities and experiences included lived experience of child sexual abuse and belonging to communities disproportionately affected by child sexual abuse. Research team members also held various positions of power and privilege, such as formal positions of authority or privilege attained through belonging to dominant groups (e.g. white privilege). The combined positionality of the research team shaped a shared recognition of the value of multiple perspectives, with an understanding that some expertise or perspectives would be more relevant to some aspects of the Standards (e.g. when privileging lived experience over sector experience, see Discussion).

Table 1. Process of integrating multiple voices and views across the design and refinement of the Minimum Practice Standards

Shaded areas demonstrate the iterative engagement of each group across the various phases of design and refinement – all groups being engaged multiple times (except for literature input) and concurrently with others to ensure a blending of the multiple voices and views

|

Multiple voices and views integrated across the design and refinement

|

Multiple phases of design and refinement over time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development of draft themes | Refinement and confirmation of draft themes to standards | Consultation | Refinement of draft standards | Validation and further consultation of draft standards | Refinement and endorsement | |

|

May–June 2022

|

June 2022

|

July–August 2022

|

August 2022

|

September–November 2022

|

December 2022–April 2023

|

|

| Project team | ||||||

|

Literature evidence base |

||||||

|

Lived experience advisory group |

||||||

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander focus groups |

||||||

|

Subject matter experts |

||||||

|

Sector (government and non-government) |

||||||

|

Government |

||||||

Research contribution – targeted literature review

A targeted evidence review of contemporary research and practice standards relevant to the development of the Standards was undertaken to generate initial themes to inform consultations and the initial structure and form of the Standards (see Horch et al., 2022 for full search terms and databases). The review obtained data from publicly available sources and published academic literature. The initial coding framework used to extract information from each source included: document information (e.g. type, intended purpose, audience); relevance to overarching standards; relevance to specialist support standards; relevance to community support standards; relevance to key priority groups standards; identified gaps for further research; identified overlap/possible themes; and relevance to the implementation of the Standards.

Targeted review of key sources

Fifty-four key sources were identified during the process of developing the project proposal. These were drawn from the knowledge of the project team, expert advisors and via pearling from source reference lists. These consisted of existing Australian service standards in related areas such as out-of-home care, child-safe organisations, mental health services and disability services; Royal Commission findings and associated reports; related professional bodies’ service standards and guiding frameworks; published service standards for responding to child sexual abuse in other countries; and existing evidence and clinical reviews of established therapeutic approaches.

Rapid review of studies of victim and survivor experiences

A rapid keyword search of studies since publication of the Royal Commission examining victim and survivor experiences of therapeutic services was undertaken to supplement these findings. In total, of 606 papers were identified in the initial sample before being screened to 11 for the final sample, targeting those that drew on the perspectives of the service experience (Horch et al., 2022). This approach was utilised to provide a rapid but replicable result, which allows for a broad collection of representative literature.

Additional sources

Nine additional sources relevant to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were also added following discussion with expert advisors. This was to provide further depth to the themes and included literature on trauma-informed frameworks and ways of working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Horch et al., 2022).

People contribution – voice and views of those with a lived experience

To ensure that the voice and views of those with a lived experience of child sexual abuse were embedded in the development of the Standards, a Lived Experience Community of Practice group (CoP) was established with the support of the Survivors & Mates Support Network (SAMSN). The CoP met formally three times over the course of the project, at different stages of development, to consider the structure, content and tone of the Standards. The group was co-facilitated by an expert advisor with specific experience in consultations with people with a lived experience and the chief executive of SAMSN, meeting for approximately seven hours in total. Several members and co-facilitators also held out-of-session discussions and communications related to the group’s feedback, including with the chief investigator. They considered both written and verbal material, including background project information, literature summaries, overarching theme summaries, sector consultation feedback and drafts of the Standards as they took shape.

The CoP group was composed of ten individuals (five males and five females), most with experience in providing consultations and advice, being active within the community and organisations that support victims, survivors and their support systems. Group members were from across Australia and had a range of experiences, including in the out-of-home care context, intrafamilial and extrafamilial child sexual abuse, abuse from both adults and other young people and institutional child sexual abuse.

Practice contribution – sector, government and expert advisory

Specialist and community support services sector consultations

Individuals from across the sector, inclusive of community sector organisations, Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations, state and federal government, peak bodies and various advisory groups, participated in one-on-one interviews, group discussions and surveys throughout the process to provide their thoughts and ideas on the themes informing the standards, and later the draft Standards.

This was the broadest and largest group of individuals and agencies consulted and included people from across the various priority groups recruited for their role within the sector that provides, develops and/or governs services, or provides system advocacy for individuals with lived experience of child sexual abuse and their supporters.

Virtual focus groups with key stakeholders and priority populations

An open invitation to participate in these consultations was distributed to over 1300 subscribers via the Australian Centre for Child Protection mailing list and various contacts related to the project, including the National Office for Child Safety mailing list, and published on various associated social media platforms. Eight virtual focus groups were conducted, including 83 individual online participants from the sector (noting that the actual number of participants is greater than 83 because some online participants included multiple people using the same participant video link, i.e. they joined the sessions as a group). Roles of participants included policy, practice, management, academic and advocacy, with practice and management having the largest representation. Noting that some responses were missing, the demographic poll data showed individual representation from non-government organisations (n = 45), government (n = 19) and private agencies (n = 12). Jurisdictional representation was present from Western Australia (n = 23), Victoria (n = 14), New South Wales (n = 13), South Australia (n = 7), Australian Capital Territory (n = 6), Queensland (n = 2) and Tasmania (n = 1). While Northern Territory representation was not identified in the demographic polls, several agencies were national and included a presence in the Northern Territory. The virtual focus groups were recorded via audio and video and the discussions were transcribed.

In the focus group sessions, an overview of the project was given and participants were asked to consider what minimum standards would be required for survivor-centred, trauma-informed, effective services. The themes derived from the literature review were presented as prompts to guide discussion. Where possible, participants were separated into small breakout rooms for smaller group discussions. Multiple themes emerged in discussions across the groups, which were fed back to the broad group and endorsed as important standards or themes.

Ongoing engagement with key stakeholders and priority populations

Further invitations to participate were sent to key organisations, peak bodies and advisory groups and contacts from jurisdictions that had limited participation in the first round of consultation. The project lead met with 17 agencies, peak bodies, advisory groups and other interested parties. Additionally, each jurisdiction and key federal agencies provided written feedback throughout the process. Participants in the key stakeholder/priority population group included: organisations providing local and national specialist services to victims, survivors and their supporters; National Centre for Action on Child Sexual Abuse; National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA); National Strategy Advisory Group; National Interjurisdictional Working Group; and peak advisory groups (https://www.childsafety.gov.au/what-we-do/engage-stakeholder-and-advisory-groups). The feedback from these groups over the course of the consultation period was quite consistent.

Targeted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander consultations

During the initial consultation phase, and later validation and refinement phase, targeted consultation sessions were held with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives from the child sexual abuse response sector. Initial invitations to participate in focus groups were sent via email to 138 individuals. In total, six individuals participated across four focus groups. The following stakeholders were represented: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander subject matter experts (n = 1); Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs) providing specialist child sexual assault services (n = 2); ACCOs and peaks supporting victims and survivors of child sexual assault (n = 1); and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff working in mainstream (non-Indigenous) specialist child sexual abuse services (n = 2).

Participants were provided with a brief overview of the project and a diagrammatic representation of principles derived from the literature, and they were asked to reflect on what the different elements mean to them. Participants were also asked to reflect on what a high-quality service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander victims and survivors might look like, and for their views on the implementation of the future Standards. Participants generally supported the concept that the Standards would apply to specialist and community support services for victims and survivors of child sexual abuse. In general, the concepts relating to each theme were endorsed. However, participants’ feedback indicated that cultural safety should not be depicted as a discrete element; rather, cultural safety should be reflected through all concepts. Participants provided several recommendations about terminology and descriptions of concepts to increase the cultural appropriateness and inclusivity of the future Standards for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. For example, Standard 4 was changed to appropriately represent an ‘evidence-informed’ rather than ‘evidence-based’ approach so as not to further preference Western system ways of knowing, which have typically been documented and evidenced through more traditional research studies compared with cultural knowledge, which has previously existed largely in verbal narratives.

Secondary sessions were also held during the refinement and validation stage of the draft Standards design. Over 180 invites were sent, with 23 participants scheduled to attend, and 10 participating. The format was in line with the initial consultation round, with general information being provided on the draft Standards and then open discussion being facilitated to gather participants’ thoughts. As with the first round, participants represented a range of organisations and experiences, including ACCOs with a specialist focus on responding to child sexual abuse (n = 1), ACCOs and peaks who support victims and survivors of child sexual abuse (n = 3), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who are subject matter experts in service delivery and sexual abuse (n = 2) and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers in non-ACCO specialist services (n = 4). The consultations largely supported the draft Standards with only minor recommendations for enhancement across each of the Standards.

Expert advisory group and subject matter expert consultation

Alongside the voice of the sector and those with a lived experience of child sexual abuse, consultation was sought from academic, practice and policy experts in this space. An Expert Advisory Group was established for the duration of the project including eight core members from across Australia with a high level of lived, cultural, practice, policy and academic expertise. Representing a range of expertise in child sexual abuse, including (but not limited to): service design and delivery; content including impacts; cultural knowledge and safety; working with adult survivors; working with children and families; quality and auditing; sector and organisational knowledge; and therapeutic responses. This group provided regular review and input into the process of developing the Standards and at various stages of development as related to their expertise.

Additional subject matter experts on child sexual abuse from across Australia were invited to participate in an adapted Delphi survey study. This included completion of two online surveys relating to the acceptability of the draft Standards at two points in time: following initial development and after further consultation and refinement. These two-round surveys were designed to identify consensus views across the subject matter experts and to capture any change in consensus across the development process. Nine participants completed both rounds of the survey.

For each round, participants were given the Value and Standard title and description inclusive of implementation indicators for the Standards. Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with five questions related to acceptability, which included: burden of implementation; perceived effectiveness; Standard coherence; opportunity costs; and general acceptability (adapted from Sekhon et al.’s (2017) seven measures of acceptability). Participants were also given a free-text option for each Standard to provide additional narrative feedback. Between round one and round two, the draft Standards were amended through consultation and refinement.

Net promoter scores (NPSs) were used as a proxy measure of overall acceptability; they were calculated by subtracting the sum of all ‘disagree’ responses from the sum of all ‘agree’-related responses and dividing the result by the sum of all responses (excluding N/A). Higher scores indicated consistency of agreement with acceptability domains, and therefore higher acceptability for all items except for ‘Implementing this standard would distract resources away from delivering services to clients’, which was negatively weighted. This item was reverse scored so that higher agreement reflected higher acceptability for all items. Any NPS above 0 indicates general acceptability as more participants agreed than disagreed with the acceptability of that standard, with 1 being the maximum achievable score of perfect agreement.

Iterative analysis

The mixed-methods approach across all rounds of data collection and analysis was largely qualitative with mostly open-ended data collection methods (e.g. focus groups and interviews). When surveys were used, these included both open-ended and closed questions and sampling was purposeful, seeking experts and key stakeholders rather than probabilistic sampling of the whole population. Sampling approaches for all phases were aimed at achieving conceptual power for analytic generalisation rather than statistical generalisations (Onwuegbuzie & Collins, 2007).

Initial consultation analysis

Data from each of the Lived Experience Community of Practice, sector consultations and targeted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander consultations were analysed both within their groups and as a collective.

Owing to time constraints, an adapted and abbreviated thematic analysis method was selected, using open (initial/ eclectic) coding to produce inductive codes (see Saldaña, 2021). Open coding allowed for a simultaneous interpretation of meaning of the data and capacity to directly observe the content of the data. This method was chosen as appropriate for understanding participant experiences and thoughts across the data set. The first pass was completed based on high-level themes generated within the sessions by the lead facilitator and the initial reading and notes taken during the facilitation of each group, codes for major topics and issues were developed and entered on an Atlas.ti file. A codebook was developed to give a definition for each code developed at this stage to assist in the initial coding. The second pass coding utilised the full transcripts, with the codebook iteratively updated as codes were changed in response to reviewing additional data. The coded material included phrases, sentences and long exchanges between individual respondents.

Each code developed yielded a set of sorted materials that provided a basis for developing a summary report. The codes were exported from Atlas.ti into a Microsoft Word file, with the coded pieces of text used as supporting materials and incorporated within an interpretative analysis. Short summaries of each code/theme were written to accompany each exported code. The work was then returned to the project and research leads for comparative analysis with other data sources. This was particularly critical given the need to consolidate multiple sources of information across these themes to enable creation, further refinement and later validation of the draft Standards.

Validation and further consultation

The draft Standards were then validated via a confirmatory consultation process, where the draft three Core Values and six Standards were tested with key stakeholders for acceptability and validity. By this final consultation phase, saturation in perspectives and feedback from all sources had been achieved with a high level of consensus, indicating a high level of acceptability of the Standards. Any minor contradictory perspectives were resolved through clarifying points or deferring to the majority view or relevant expertise group.

Online survey with key stakeholders and priority populations

Similar to the Subject Matter Expert survey, a single-round survey was designed to increase engagement and test the acceptability of the draft Standards with the sector. The survey was completed by 33 participants, with the majority of participants in areas of advocacy, management and practice; all jurisdictions were represented in this sample.

As with the previous survey, participants were given the Value and Standard title and description inclusive of implementation indicators for the Standards, and were then asked to rate their level of agreement across the five acceptability domains and provide any additional narrative feedback. Net promoter scores were again used as a proxy measure of overall acceptability. A table summarising the qualitative feedback was prepared to organise the commentary by draft Standard and Value so it could be considered within the context of other feedback.

Ongoing engagement with key stakeholders and priority populations

Key organisations, peak bodies and advisory groups with limited participation in the first round of consultations were invited to complete a brief validation survey rating their perceived importance of each of the six draft Standards and the three Core Values. Seventeen participants across the two groups participated in the survey following discussion with the project lead and provision of key statements describing each of the draft Standards and Core Values. Perception of importance for inclusion in the final Standards was rated on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 reflecting ‘Shouldn’t be a minimum Standard’ and 10 being ‘Must be a minimum Standard’.

Final refinement of draft Standards

Following the sector surveys and final targeted consultations as described above, the draft Standards were refined with input from NOCS, project team members and Australian states and territory governments.

Results

Multiple sources of information were integrated at each phase of the design and validation process to develop the Standards. A defining result at each phase was the refinement of each of the themes and later individual standards.

Development of draft themes

Thematic analysis of the 72 data sources from the literature review yielded 12 initial themes with a series of subthemes, which was refined via a secondary review into seven themes with an overarching theme of ‘Survivor-centred, trauma-informed effective services’ (see Table 2).

Table 2. Literature-derived themes

| Initial deductive literature themes | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Collaboration |

| 2. | Validation of clients |

| 3. | Respect for autonomy |

| 4. | Assessment of needs |

| 5. | Professional competencies |

| 6. | Evidence/practice based |

| 7. | Accessibility |

| 8. | Holistic care |

| 9. | Recovery orientation |

| 10. | Person-centred care |

| 11. | Rights of clients |

| 12. | Governance |

| Secondary inductive literature themes | |

| 1. | Survivor-centred, trauma-informed, effective services |

| 2. | Skilled workforce |

| 3. | Culturally safe |

| 4. | Inclusive and respectful of diversity |

| 5. | Empowerment |

| 6. | Safe from harm, shame, blame and re-traumatisation |

| 7. | Articulated approach and way of working |

| 8. | Organisational leadership and governance |

Transformation of themes into draft Standards

Initial themes from the literature were integrated with the themes that emerged from the consultation analysis, via further discussion with the Lived Experience Community of Practice group, Expert Advisory group and the project team (inclusive of government representation). Six draft Standards with descriptive indicators, and three Core Values were created. See Table 3.

Table 3. Initial draft Standards and Core Values

| Standards | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Safety, choice and control |

| 2. | Accessible and inclusive |

| 3. | Holistic and integrated responses |

| 4. | Service design and approach |

| 5. | Skilled and supported workforce |

| 6. | Organisational governance |

| Core Values | |

| 1. | Cultural safety |

| 2. | Trauma informed |

| 3. | Victim and survivor centred |

Validation and further consultation

Adapted Delphi measuring acceptability

Each Standard was rated within round one of the adapted Delphi between NPS 0.42 for Organisational leadership and governance to Safe from harm, shame, blame and re-traumatisation with NPS 0.76. Although most of the narrative commentary was related to implementation considerations for the Standard, some related to advice on how to improve the standard. Following presentation of the refined Standards in round two (which included variations to five of the Standards, and inclusion of a new Standard – Holistic and integrated response), each Standard was again rated well on all domains of acceptability. Table 4 shows NPSs across both rounds and shows substantial increase between round one and round two in terms of acceptability across domains for all five standards that were presented previously. Support for Organisational leadership and governance was particularly marked.

Table 4. Net promoter scores (NPSs) for Delphi round 1 and 2

| Standard | NPS round 1 | NPS round 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Organisational governance (previously Organisational leadership and governance) | 0.42 | 1.00 |

| Skilled and supported workforce (previously Skilled workforce) | 0.58 | 0.71 |

| Safety, choice and control for clients (previously Safe from harm, shame, blame and re-traumatisation) | 0.76 | 0.93 |

| Accessible and inclusive services (previously Inclusive and respectful of diversity) | 0.45 | 0.65 |

| Holistic and integrated response (new Standard) | – | 0.74 |

| Service design and approach (previously Articulated approach and way of working) | 0.55 | 0.91 |

Online survey with key stakeholders and priority populations measuring acceptability

All the draft Standards achieved a high level of acceptability, with Safety, choice and control (0.85) and Organisational governance (0.84) receiving the highest scores compared with the other draft standards, and Skilled and supported workforce receiving the lowest score (0.69) in comparison with other draft standards (Accessible and inclusive services, 0.77; Holistic and integrated responses, 0.78; Service design and approach, 0.75).

This demonstrates that overall, most participants rated the draft Standards as acceptable across all domains measured. Perceived effectiveness, coherence and general acceptability domains were all rated very highly, with either no disagreement or minimal disagreement and neutral responses. Although they still received strong endorsement, burden and opportunity costs received a small percentage of neutral and disagree responses across all the draft Standards. This suggested that all the draft Standards were generally acceptable, with minimal changes needed, and that there was a small proportion of the sector with concerns about implementing the Standards, which aligned with initial expectations that the sector would have gaps in responses.

Overall, the qualitative feedback for each Standard fell into four main categories: suggested edits or additions; endorsement of the Standard or some aspect of it; commentary about the sector or implementation; and critiques of some aspect of the Standard that may require further consideration. The suggested edits and additions were minor in nature, which further indicated that the Standards were generally acceptable as they were. The critique indicated that the Standards were generally acceptable to the participants once some aspect was edited or developed further. The commentary feedback generally did not suggest that the Standards should be changed, but rather acknowledged that there are services that would not be able to meet the Standards, indicating that there are potential capacity gaps in the sector. The comments endorsing the Standards also spoke further to the acceptability of the Standards, particularly as many comments that provided commentary about implementation challenges also endorsed the Standards.

Online survey with key stakeholders and priority populations measuring perceived importance

Scores ranged from 9.4 (Effective organisational governance) to 9.9 (Evidence-informed and articulated service approach) out of possible 10, demonstrating that each of the Standards were highly relevant to these participants. Participants rated the three Core Values even stronger, with Victim and survivor centred scoring a 10, Trauma-informed a 10 and Culturally safe a 9.9.

Final refinement to draft standards

Overall, the feedback indicated that the draft Standards were generally acceptable, with only minor revisions suggested over time. Written feedback from government reached saturation quickly, with only minor commentary unresolved. The feedback that was unresolved related more to implementation or nuances that were related to specific areas of focus.

Endorsed minimum practice standards

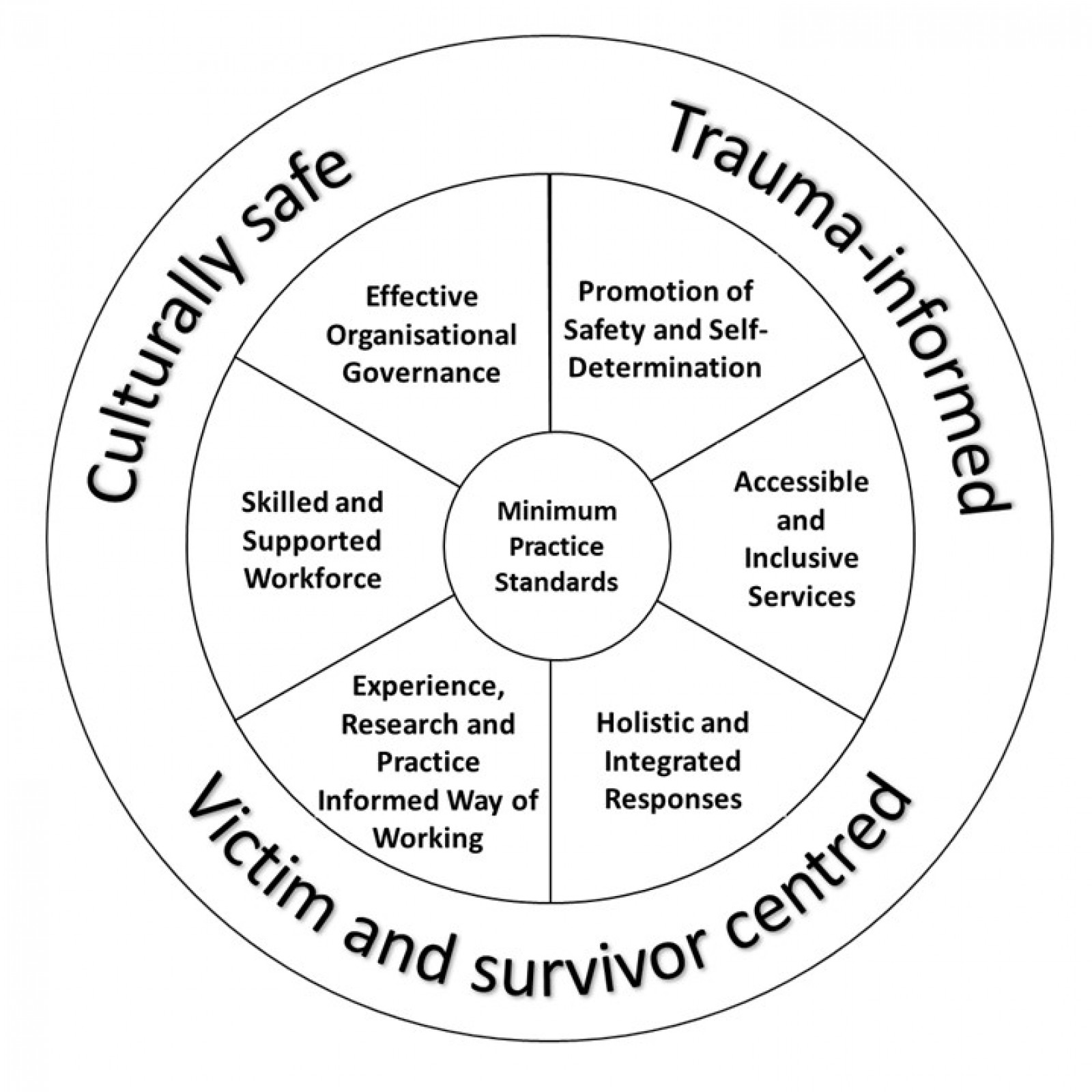

The final Standards were published by the National Office for Child Safety (Paton et al., 2023) following full endorsement by each jurisdiction and the federal government. The Standards include six Standards and three Core Values (see Figure 1 below). Each Standard includes a definition (key statement), several indicators that allow for the operationalisation of the Standards and value statements that articulate how each of the Core Values can be represented within each Standard.

Figure 1. Final Minimum Practice Standards (Paton et al., 2023). This figure includes the six Standards and the three Core Values of the Standards at a glance

Discussion

This paper has explored the complex and iterative consultation process used to develop the Standards. The multiple-informants-based methodological approach taken was to ensure that the Standards were suitable and acceptable to both the sector, which will implement them, and the victims, survivors and their support system, who would ultimately be beneficiaries of their implementation. It was imperative to include multiple perspectives to ensure that practice, cultural and lived experience wisdom made equal contributions to the Standards as the literature, which would safeguard against gaps in any single body of knowledge. The process represented a continuous cycle of refinement from themes to standards until consensus was reached. Subsequently, the final Standards have been widely endorsed, arguably due to this broad approach, which included: input from individuals with a lived experience of child sexual abuse and their supporters; the service sector, including government and non-government organisations, advisory groups and peak bodies; subject matter experts (with lived, practical, policy, quality, academic and cultural expertise); Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; and representatives from diverse groups, including LGBTQIA+, disabled communities and those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

The goal of developing the Standards was to improve outcomes for victims and survivors of child sexual abuse by ensuring that, regardless of location, background or experience, each had access to high quality services to support their needs in a safe, effective and trauma-informed way. To achieve this, it was imperative that the consultation and design methodology considered the implementation of the Standards just as much as the content. Well thought out implementation processes that begin with robust design methodology are often seen as critical to ensuring that change (whether that be services, models of practice or broader system reforms) occurs as intended and, more importantly, that it has the best chance to be maintained over the long term. To enable successful implementation, four stages are typically required (National Implementation Research Network 2013-2019):

- Exploration – engagement and consultation with stakeholders recognising that the system needs to change to better support those it services. It answers the question of why change is needed and what change would look like. If done well, this creates ownership within those consulted;

- Installation – putting the change into practice and monitoring early concerns, feedback and progress;

- Initial implementation – system change is in place and a continuous quality improvement process and governance structures can monitor change; and

- Full implementation – the change becomes a part of business as usual. Further it considers both the barriers to implementation and implementation drivers.

This project focused on the Exploration phase, engaging and consulting with stakeholders, so that ownership of the Standards could be achieved by victims and survivors and the sector to ensure successful adoption of the Standards.

It is recognised that implementation barriers, such as system readiness, lack of commitment from leadership, capacity, a culture of unwillingness to change, inadequate resources, instability, poor working relationships, top-down approaches etc, are often overlooked during the Exploration and early Installation phases and subsequently change fails to occur (Fixen, et al 2009). Not because change wasn’t needed or the proposed mechanism to achieve change was wrong (although this can also occur), but because the process of developing the change was poorly designed and failed to consider later implementation (Durlak, 2011). Whilst this highly consultative process was necessary to ensure that many of the implementation barriers were overcome, this was not without its challenges. Trying to balance the multiple perspectives was sometimes fraught. For example, specific inclusion of indicators related to acknowledgement of past institutional child sexual abuse responsibility was critically important for those with a lived experience of child sexual abuse; this represented a level or trust and transparency of a service, so they felt this was important to have reflected in the Standards. Conversely, some participants from the sector were cautious with this inclusion owing to the perceived lack of control a service may have over such a decision, which is held at an organisational level and may come with potential negative ramifications. In these instances, where there were tensions between the multiple voices considered, the project team consulted with members of the expert group from a range of perspectives and made the final decision. In the instance above, the final Standard ‘Effective organisational governance’ includes a specific indicator (e.g. 'Where an organisation has a history of association with past failures to protect children or young people in their care from sexual or other abuse, these need to be transparently disclosed along with the actions taken to address these issues'; Paton et al., 2023: p. 24).

Other difficult considerations included those related to the notion of minimum – that is creating a set of Standards that were set at a level that was a minimum benchmark, and not best practice. This was most evident within the Standard ‘Skilled and supported workforce’, where there was considerable discussion across all informant groups with regards to what is required to create safe, trauma-informed and effective services for victims and survivors, and what was achievable within a service system that many described as broken. The ‘broken’ description referred to the extensive waitlists, inconsistent accessibility across the jurisdictions and within regions, difficulty attracting and retaining staff and persistent funding and commissioning issues for services, all of which hinder sustainability. Whilst it was recognised amongst groups that some services and jurisdictions were not impacted as much by these issues, or in the same way, the question became how to design a set of standards that is suitable and realistic for all. With consideration for this, the project team had to take an unapologetic approach, including what was required to provide safe, trauma-informed and effective services for victims and survivors of child sexual abuse and their supporters, even knowing that some services would need considerable support and capacity building to come close to meeting some standards or sub indicators.

Limitations

Participants contributing to the consultations were largely from metropolitan services provided by government and community sector organisations, with smaller numbers from regional and remote areas across Australia, or from Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations. Whilst this is more representative of the current service system mix, it may have given preference to more mainstream views from a metropolitan perspective.

Further, the largely qualitative methods have been influenced by the primary researchers’ positionality through a process of reflexivity in refining themes, translating these into standards and incorporating feedback. Whilst the research team included a variety of views and experiences (both professional and personal), the influence of the reflexive approach cannot be ignored, and had the Standards been developed by a different researcher group, they may have yielded slightly different statements.

Aside from the methodological limitations of the qualitative process of design, the Standards themselves carry some implementation limitations. For example, many services will require implementation support to further operationalise these Standards and self-assess against the indicators. Issues such as funding constraints, capacity and access to training for staff, ability to develop aligned processes and practices, and capability to create organisational culture change will likely disproportionately impact smaller agencies and those in regional and remote areas.

Strengths and implications for implementation

Notwithstanding these limitations, it is expected that the strengths of this work will support implementation of the Standards. The inclusion of a broad range of stakeholders and perspectives within a participatory approach allowed for learning across the sector through the process. For example, during the focus groups with the sector, many practitioners shared innovative approaches to the challenges faced by the sector. The services taking these approaches were not always larger or better funded. Not only were these approaches woven into the Standards but others participating may have been able to take that learning to their service. Additionally, the Standards and companion material were written with small, underfunded services in mind. The implementation guide (available via childsafety.gov.au) is intended to support services to find what they are doing well, what could be improved upon and develop a plan to improve where needed.

Furthermore, although the Standards focus on services and organisations, they may provide support for systems-level change. Many of the indicators articulate the work that individual services and organisations should be doing to provide safe and effective care for victims and survivors of child sexual abuse outside of direct service provision. For example, Standard 3 (Holistic and Integrated Responses) has several indicators referring to collaboration between services to meet the needs of victims and survivors, particularly where services have gaps in expertise (e.g. lack of cultural expertise). Services need to be able to spend time building relationships with other services and organisations and then develop system infrastructure to support collaboration (such as safe and secure referral pathways). Doing this work should lead to reduced siloes between service systems, thereby reducing a key systemic barrier to trauma-informed, culturally safe, victim and survivor-centred service provision. Currently, services are rarely funded sufficiently to engage in this kind of collaboration. However, by articulating the minimum expectations for safe and effective service provision for victims and survivors, the Standards may support funding bodies to understand and appropriately fund all of the activities required.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the final Standards, including six standards and 58 indicators, underpinned by three Core Values, provide a clear pathway for services to create and sustain safe and effective services that support victims, survivors and their support system who have experienced or been impacted by child sexual abuse. These Standards can also assist victims, survivors and their support system to make informed choices about the services they seek and give guidance on what they should expect from services.

Implementation and assessment of services against these Standards is the next step in fulfilling the goal to have services in Australia that are victim and survivor centred, trauma informed and culturally safe, responding to victims and survivors of child sexual abuse and their support system. It is hoped that implementation of the Standards will be supported by the methodological strength of this approach, which included multiple perspectives and an iterative process of design following multiple points of consultation. The Standards have been designed with and for the sector and those with a lived experience of child sexual abuse, aligning with the recommendations from the Royal Commission, to improve trauma-informed, culturally safe and victim and survivor-informed service responses.

The implementation challenges raised through this work demonstrate just how needed the Standards are to address the gaps that exist across the sector. The development of these Standards and their implementation takes place within the context of the National Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Child Sexual Abuse and the NAP. Both have dedicated measures designed to improve systems, including training and development of needed infrastructure to enhance trauma-informed, culturally safe and victim and survivor-centred services. The Standards are an important contribution to this suite of measures and have the potential to achieve the intended outcomes of the Royal Commission recommendations, the National Strategy and, ultimately, outcomes for victims and survivors of child sexual abuse in Australia.

Acknowledgements

Associate Professor James Herbert, Professor Vickie Hovane, Professor Patrick O’Leary, Sian Burgess, Jenny Scott and Dr Martine Hawkes for various contributions to related reports informing this process.

Special thanks also go to the Lived Experience Community of Practice Group, convened by the Survivors and Mates Support Network (SAMSN) CEO Craig Hughes-Cashmore, for generously sharing their knowledge and experiences. We also thank other victims and survivors of child sexual abuse who shared with us.

We acknowledge individuals, peaks and organisations from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities who participated in workshops, surveys, and rich discussions. We thank you for sharing your knowledge and experiences. We would also like to thank the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) for their support with seeking feedback from members and providing advice and guidance.

We acknowledge members, peaks and organisations across Australia from the non-government community sector for their generous participation and contribution throughout this project: for sharing their views, reflecting on system challenges and providing feedback.

We would also like to acknowledge and thank government representatives across Australia from state, territory and Commonwealth agencies who have contributed to this project and final development of the Standards, particularly the National Office for Child Safety.

Funding statement

This work was supported by funding from the National Office for Child Safety (NOCS), Attorney-General’s Department. AusTender number – CN3877315-A1.

References

Alla, K., & Joss, N. (2021). What is an evidence-informed approach to practice and why is it important? Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. aifs.gov.au https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/2021/03/16/what-evidence-informed-approach-practice-and-why-it-important

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. (2020). AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. aiatsis.gov.au https://aiatsis.gov.au/research/ethical-research/code-ethics

Australian Institute of Family Studies. (2015). Participatory action research. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. aifs.gov.au https://aifs.gov.au/resources/practice-guides/participatory-action-research

Cashmore, J., & Shackel, R. (2013). The long-term effects of child sexual abuse. CFCA Paper No. 11. Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies. apo.org.au https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2013-02/apo-nid32750.pdf

Duffee, J., Szilagyi, M., Forkey, H., Kelly, E. T., Council on Community Pediatrics, Council on Foster Care, Adoption and Kinship Care, Council on Child Abuse and Neglect & Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child Family Health. (2021). Trauma-informed care in child health systems. Pediatrics, 148(2), e2021052579. DOI https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-052579 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34312294

Durlak, J. A. (2011). The Importance of implementation for research, practice, and policy. Child Trends Research Brief. Washington, DC, USA: Child Trends. cms.childtrends.org https://cms.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/2011-34DurlakImportanceofImplementation.pdf

Fixen, D. L., Blase, K. A., Naoom, S. F., & Wallace, F. (2009). Core implementation components. Research on Social Work Practice, 19, 531–540. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509335549

Fong, H. F., Bennett, C. E., Mondestin, V., Scribano, P. V., Mollen, C., & Wood, J. N. (2017). Caregiver perceptions about mental health services after child sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 51, 284–294. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.09.009 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26602155

Fong, H. F., Bennett, C. E., Mondestin, V., Scribano, P. V., Mollen, C., & Wood, J. N. (2020). The impact of child sexual abuse discovery on caregivers and families: A qualitative study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35, 4189–4215. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517714437 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29294788

Horch, G., Herbert, J., Parsons, V., & Paton, A. (2022). Baseline analysis of specialist and community support services for victims and survivors of child sexual abuse: Literature review summary – revised. Australia: National Office for Child Safety.

Mathews, B., Pacella, R., Scott, J. G., Finkelhor, D., Meinck, F., Higgins, D. J., Erskine, H. E., Thomas, H. J., Lawrence, D. M., Haslam, D. M., Malacova, E., & Dunne, M. P. (2023). The prevalence of child maltreatment in Australia: Findings from a national survey. Medical Journal of Australia, 218(S6), S13–S18. DOI https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.51873 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37004184

National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council & Universities Australia. (2018). National statement on ethical conduct in human research 2007 (updated 2018). Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council. nhmrc.gov.au https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/national-statement-ethical-conduct-human-research-2007-updated-2018#block-views-block-file-attachments-content-block-1

National Implementation Research Network (NIRN). (2013–2019). Stages. Chapel Hill, NC, USA: SISIP, University of North Carolina. implementation.fpg.unc.edu https://implementation.fpg.unc.edu/implementation-practice/stages/

National Office for Child Safety. (2021). National strategy to prevent and respond to child sexual abuse 2021–2030. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. childsafety.gov.au https://www.childsafety.gov.au/resources/national-strategy-prevent-and-respond-child-sexual-abuse-2021-2030

Okoko, J. M. (2023). Action research. In J. M. Okoko, S. Tunison & K. D. Walker (Eds). Varieties of qualitative research methods. (pp. 9–13). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Collins, K. M. T. (2007). A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. The Qualitative Report, 12(2), 281–316. files.eric.ed.gov https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ800183.pdf

Paton, A., Parsons, V., Pitts, C., Adamson, K., Bromfield, L., Horch, G., Herbert, J., Hovane, V., O’Leary, P., & Burgess, S. (2023). Minimum Practice Standards: Specialist and community support services responding to child sexual abuse. Canberra: National Office for Child Safety. childsafety.gov.au https://www.childsafety.gov.au/system/files/2023-08/minimum-practice-standards-specialist-community-support%20Services-responding-child-sexual-abuse.PDF

Quadara, A., & Hunter, C. (2016). Principles of trauma-informed approaches to child sexual abuse: A discussion paper. Sydney: Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. apo.org.au https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2016-11/apo-nid69750.pdf

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. (2017a). Final report: Volume 3, Impacts. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/final_report_-_volume_3_impacts.pdf

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. (2017b). Final report: Volume 9, Advocacy, support and therapeutic treatment services. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/final_report_-_volume_9_advocacy_support_and_therapeutic_treatment_services.pdf

Ruiz, E. (2016). Trauma symptoms in a diverse population of sexually abused children. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(6), 680–687. DOI https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000160 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27243569

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 4th edn. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

Saunders, K. R. K., McGuinness, E., Barnett, P., Foye, U., Sears, J., Carlisle, S., Allman, F., Tzouvara, V., Schlief, M., Vera San Juan, N., Stuart, R., Griffiths, J., Appleton, R., McCrone, P., Rowan Olive, R., Nyikavaranda, P., Jeynes, T., T, K., Mitchell, L., Simpson, A., Johnson, S., & Trevillion, K. (2023). A scoping review of trauma informed approaches in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care. BMC Psychiatry, 23, 567. DOI https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05016-z PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37550650

Scott, J. G., Malacova, E., Mathews, B., Haslam, D. M., Pacella, R., Higgins, D. J., Meinck, F., Dunne, M. P., Finkelhor, D., Erskine, H. E., Lawrence, D. M., & Thomas, H. J. (2023). The association between child maltreatment and mental disorders in the Australian Child Maltreatment Study. Medical Journal of Australia, 218(6), 26–33. DOI https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.51870 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37004186

Sekhon, M., Cartwright, M., & Francis, J. J. (2017). Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Services Research, 17, 88. DOI https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28126032

Stoltenborgh, M., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Euser, E. M., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2011). A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment, 16(2), 79–101. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559511403920 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21511741