Article type: Original Research

20 September 2024

Volume 46 Issue 1

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 3 June 2024

REVISED: 11 July 2024

ACCEPTED: 26 July 2024

Article type: Original Research

20 September 2024

Volume 46 Issue 1

HISTORY

RECEIVED: 3 June 2024

REVISED: 11 July 2024

ACCEPTED: 26 July 2024

![]() Exploring parents’ understanding of children’s learning through the lens of belonging, being and becoming within the Early Years Learning Framework for Australia

Exploring parents’ understanding of children’s learning through the lens of belonging, being and becoming within the Early Years Learning Framework for Australia

Affiliations

1 School of Education, Deakin University, Burwood, Vic. 3125, Australia

Correspondence

*Dr Karen Guo

Contributions

Karen Guo - Study conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting of manuscript, Critical revision

Karen Guo1 *

Affiliations

1 School of Education, Deakin University, Burwood, Vic. 3125, Australia

Correspondence

*Dr Karen Guo

CITATION: Guo, K. (2024). Exploring parents’ understanding of children’s learning through the lens of belonging, being and becoming within the Early Years Learning Framework for Australia. Children Australia, 46(1), 3011. doi.org/10.61605/cha_3011

© 2024 Guo, K. This work is licensed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Abstract

Numerous studies have emphasised the importance of parents’ knowledge of children’s learning and their input in early childhood education. Over the past 15 years, the Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF) has been central to Australian early years education, generating extensive scholarly literature on its concepts and applications. However, there remains a notable gap in research utilising the EYLF to investigate parents’ perspectives on children’s learning. The present study addressed this gap by examining how preschool parents perceived children’s learning in early childhood education, drawing on the foundational concepts of ‘being’, ‘belonging’ and ‘becoming’ from the Framework. A sample of 48 preschool parents participated in the study, responding to a 12-item questionnaire designed to investigate three main questions: How do children learn? What are the priorities in children’s learning? What are the influences on children’s learning? Findings from the study indicated that parents prioritised nurturing their children’s sense of being, while also recognising the importance of belonging and becoming, aligning with the fundamental aspirations for children’s learning outlined in the EYLF. Moreover, parents perceived early childhood settings, particularly the roles of teachers and children’s peers, as essential for fostering a wide range of learning experiences, reflecting contemporary early childhood discourses. These results shed light on how professional and unprofessional boundaries that are defined between early childhood educators and parents need to be renavigated, emphasising the importance of parenting knowledge in shaping children’s educational experiences and highlighting the necessity of collaborative efforts and equal positions between parents and educators to optimise children’s learning and development.

Introduction

For decades, researchers and advocates have expressed concerns about the disparities between parents’ knowledge and the learning programmes provided to young children in early childhood education. Several dichotomies emphasise the need for early childhood professionals to understand parents’ insights into their children’s learning. First, while a fundamental task of parenting involves supporting children’s acquisition of skills essential for adapting to their local communities (e.g. Gadsden et al., 2016; Jeong et al., 2021), teachers often prioritise the development of general capabilities and learning dispositions (e.g. Jackson, 2021). Second, parents play a crucial role in transmitting values, rules and standards specific to their families or cultural backgrounds. In contrast, teachers interact with each child as an individual, guiding them through established approaches and policy standards (e.g. Gadsden et al., 2016; Jackson, 2021; Jeong et al., 2021). Third, parents’ beliefs and practices are deeply influenced by the norms and expectations of their communities, serving as core conduits for perpetuating cultural priorities, while teachers apply their philosophies in their interactions with each child (e.g. Jeong et al., 2021; Jackson, 2021). Although both parents and teachers share the overarching goal of supporting children’s learning and development, the differing knowledge and practices they bring to the table may not be optimally utilised unless teachers understand and incorporate parents’ knowledge and expectations. While the limitations of disregarding parental input are widely acknowledged, few researchers have investigated in this area beyond advocating for closer involvement of parents in their children’s education.

Rouse and O’Brien (2017) described how, despite ‘best intentions’, the idea that teachers are experts is often perpetuated in their partnership practice with children’s families in Australian early childhood education. This issue is further complicated when the policy documents that guide teachers’ work provide ambiguous guidelines, where ‘the language used across the two key policy documents, the Early Years Learning Framework and the National Quality Standard, is inconsistent in the way these partnerships are defined and intended to be enacted’ (p. 45). Kwong et al. (2018) suggested that parenting knowledge is a rich, multi-layered resource from which effective learning programmes can be developed. Families are the child’s first teachers. Therefore, understanding what parents know and want to know is essential for connecting with children’s life worlds in their learning. This highlights the critical need for further exploration of parents’ perspectives and knowledge, emphasising the importance of acknowledging and leveraging the unique contributions they bring to children’s learning experiences.

The present research is positioned within the Australian context, where early childhood teachers often find working with children’s parents challenging. The objective of the research is to explore the perceptions and expectations of a group of parents regarding their children’s learning. The research uses the key visions of the EYLF to analyse parents’ perspectives. Herein, ‘Australian parents’ refers to all parents residing in Australia whose children are enrolled in early childhood services, irrespective of their backgrounds.

Australian early childhood education

Early childhood education in Australia includes both preschool and the early years of formal schooling, spanning from birth to 8 years old and catering to a diverse range of children (Raban, 2011). During this critical developmental period, children receive both education and care. Common early childhood education services include long daycare, which offers comprehensive care and education for children from birth to 5 years, and sessional kindergarten/preschool, providing structured education and care for 3 to 5 year olds.

Although historically not prioritised, early childhood education and care experienced a significant turning point on 29 November 2008, when the Council of Australian Governments endorsed the National Partnership Agreement on Early Childhood Education (NP ECE). This agreement marked a joint commitment by the Australian Government and all state and territory governments to provide high-quality early childhood education and care for young children. Among the various reforms introduced under this partnership, a notable policy was the establishment of the National Early Years Learning Framework. Named ‘Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (EYLF)’, this framework serves as a guiding curriculum document for early years education in Australia. It defines children’s learning and asserts that ‘fundamental to the Framework is a view of children’s lives as characterised by belonging, being and becoming’ (Australian Government Department of Education (ADGE), 2022: p. 6).

The Framework also includes principles, practices and learning outcomes, which it views as ‘fundamental to early childhood pedagogy and effective curriculum decision-making’ (ADGE, 2022: p. 7). In particular, the learning outcomes provide directions in children’s learning, with the aim to ‘capture the integrated and complex learning and development of all children’ (ADGE, 2022: p. 29). These outcomes address children’s diverse needs and learning trajectories as follows:

- Identity: Fostering a sense of self-awareness and personal identity;

- Connection and Contribution: Encouraging engagement and contribution to communities and the broader world;

- Wellbeing: Promoting physical, emotional and social wellbeing;

- Confidence and Involvement in Learning: Cultivating self-assurance and active participation in the learning process; and

- Effective Communication: Developing strong communication skills.

Underpinned by the concepts of belonging, being and becoming, the interrelated elements of principles, practice and learning outcomes support early childhood educators in creating tailored learning experiences that promote holistic development for each child. Additionally, the EYLF emphasises the important role of families as children’s primary educators. Central to this Framework is the principle of ‘partnerships’, advocating for collaborative relationships between educators and families in decision-making processes regarding the curriculum. The ethos of partnership permeates various aspects of the EYLF’s practices, including holistic approaches to education, cultural responsiveness and ensuring continuity of learning and smooth transitions.

In an endeavour to explore the topic, the present study is grounded in the defining concepts of belonging, becoming and being within the EYLF. In rapidly changing, mobile and diverse societies, like those in Australia, a single concept cannot fully capture the complexities of children’s experiences. Situating parents’ perspectives within a comprehensive conceptual framework is arguably the most crucial starting point for understanding their knowledge about children’s learning and development.

Belonging, Being and Becoming as the defining concepts in children’s learning

The concepts of belonging, being and becoming, rooted in Western philosophies (Peers & Fleer, 2014), have gained ontological status as influential foundations for early childhood research and practices. These concepts are increasingly significant in defining children’s learning and development. By incorporating these concepts in the EYLF, Australian early childhood education aims to achieve a comprehensive understanding of children’s needs, characteristics and potentials, effectively bridging practical experiences with theoretical underpinnings inherited from philosophical traditions.

Belonging

In the EYLF, belonging is depicted as an essential aspect of human existence. It revolves around the notion of ‘knowing where and with whom you belong’ (AGDE, 2022: p. 6), emphasising that children belong ‘to diverse families, neighbourhoods, local, and global communities’. The concept of belonging underpins the belief that children interact independently with others, and these interactions form the foundation for defining their identities. From early childhood into adulthood, cultivating trusting relationships and affirming experiences is paramount for fostering a sense of belonging (Strycharz-Banaś et al., 2020).

Recognising and embracing differences and diversity is recognised as a foundational aspect of belongingness. According to Peers and Fleer (2014), belonging involves acknowledging diverse individuals and the potential for a shared identity or togetherness, where diverse individuals are situated, understood and connected. The significance of diversity in early childhood settings prompts scholars and policymakers to reconsider the fundamental principles underlying children’s learning and teaching. Therefore, by prioritising belonging within the EYLF, there is also an aspiration to redirect the focus towards a more nuanced understanding of child development, one that respects individuals for their unique identities and their connections with others.

Emphasising that belonging encompasses both diversity and individuality, it is highlighted within the EYLF how this concept serves as a means to understand various dimensions of children’s learning, from self-centred and independent experiences to social and interpersonal interactions. It acts as a meeting point between the notions of self and others, providing a site for children to explore and negotiate different facets of their identity (Strycharz-Banaś et al., 2020).

Being

The assertion that ‘being is the core of our existence, and thus fundamental to early childhood’ (Knaus, 2015: p. 225) is one of the most influential themes shaping contemporary early childhood curriculum. This concept resonates with the advocacy for children’s rights, agency and identity, emphasising the protection of childhood as a distinctive stage of human development. The significance of ‘being’ is clearly articulated in the EYLF where it is described as ‘a time to be, to seek and make meaning of the world’ (AGDE, 2022: p .6). ‘Being’ acknowledges the importance of both the present moment and the past in children’s lives. It includes children’s understanding of themselves, the development of their identity, the establishment and nurturing of relationships, engagement with life’s joys and complexities and the navigation of challenges in everyday life. ‘The early childhood years are not solely preparation for the future but also about children being in the here and now’ (AGDE, 2022: p. 6). ‘Being’ represents the unique combination of characteristics that define each child’s individuality, aligning with the EYLF learning outcome that states, ‘Children have a strong sense of identity’ (AGDE, 2022: p. 30).

The concept of being is intricately intertwined with the concepts of belonging and becoming. As Mulhall (2000) suggested, our understanding of being is shaped by our interactions with others in the world around us. While children are undoubtedly individuals, they absorb specific cultural traits from those who hold significant influence in their lives, often spending considerable time outside their own homes in social settings, such as early childhood services. Within the contexts of coexistence with others, they adopt and adjust to various social and cultural values, roles and functions as they engage with their environment (Mulhall, 2000). According to Knaus (2015), being is considered the cornerstone of all three defining concepts in the EYLF, serving as the pathway through which belonging and becoming are realised in children’s learning.

Becoming

Peers and Fleer (2014) defined ‘becoming’ as a representation of change or developing towards something. Within the EYLF, becoming is characterised as ‘a process of rapid and significant change that occurs in the early years as children learn and grow’ (AGDE, 2022: p. 6). Despite its incorporation into the curriculum framework, the concept of becoming has also faced scrutiny in children’s learning. Kuby and Vaughn (2015: p. 437) cited Uprichard’s (2008: p. 303) critique, which argued that ‘the becoming child is perceived as an adult in the making, lacking the competencies of the adult they will become’. This focus on the future, or what a child will become, may imply a lack of competence, thereby undervaluing the ways in which children already exist, act, know, construct and interact with their realities.

Just as the Framework suggests that the concepts of becoming, being and belonging are interrelated and overarching in children’s learning, Uprichard (2008) proposed integrating being and becoming to address this concern. This integration aims to acknowledge the temporality of these concepts and enhance the child’s agency in learning. For Uprichard and others (Peers & Fleer, 2014), becoming should not solely imply a future goal or end result. Instead, it should illuminate the fluid and intricate nature of young children’s existence, showing how they become creators with materials and how their identities evolve. This is similar to the concept of belonging, which has been claimed to consist of many manifestations and dynamics with a ‘multilayered nature’ (Sumsion & Wong, 2011: p. 32).

By prioritising becoming and accentuating being and belonging within a broader context, the fluidity and intricacy of learning and development in early childhood are recognised. The concept of becoming thus implies that children’s exploration and understanding of the world involve transitions between different states of existence and levels of growth, acknowledging the multitude of changes children encounter as they learn and grow (Leggett & Ford, 2016).

Methods

This article originates from a comprehensive project focused on children’s learning in group settings, which employed a three-part perspective encompassing the viewpoints of parents, children and early childhood educators. Parental perspectives were gathered through open-ended survey questions. Due to time constraints, parents were unable to participate in face-to-face interviews; therefore, qualitative questions were incorporated into the survey questionnaire, allowing parents to respond at their convenience.

Participants and procedure

The study involved 48 participants recruited evenly from three preschools in metropolitan Melbourne, Australia, serving children aged 4 to 6 years. There were 16 parents from each preschool included in the study. The preschools were chosen from diverse socio-economic areas to obtain a more comprehensive perspective and inform the research more effectively than focusing on similar communities. Among these participants were 43 mothers and five fathers, representing 41 families. Their ages ranged from 26 to 48. Among the participants, 27 had one child, 16 had two children and five had more than three children of preschool age. These parents voluntarily joined the study following information provided by the preschools. They represented diverse backgrounds, including professionals engaged in paid work and stay-at-home parents.

The questionnaire, designed to gather qualitative responses, consisted of 19 items organised into four sections. Preschool teachers assisted in distributing the surveys to parents and collecting them upon completion. The first section comprised seven demographic questions, covering parents’ age, family structure, gender, formal education, profession, and the duration of their child’s or children’s enrolment in preschool. The second section featured two open-ended questions related to preferred approaches for children’s learning, encompassing parents’ views on how children should learn and what approaches lead to desirable learning experiences and outcomes in young children. The subsequent section included four questions eliciting parents’ views on what children should learn, with a specific emphasis on identifying priorities across various areas of learning. The final section, consisting of six questions, focused on influential factors, including the role of children as learners, the influence of social contexts on children, their learning experiences within both family and preschool settings, parents’ perceptions of contextual differences in children’s learning, contributing factors, and parental expectations for children’s learning at present and in the future. The survey concluded with an invitation for parents to provide additional open comments on the research topic. Overall, completion of the survey required approximately 15 minutes.

Both statistical and content analyses were conducted, involving the calculation of results and the categorisation of content to identify patterns and themes. This mixed-analytical approach is particularly significant in social sciences as it combines quantitative and qualitative methods to enhance understanding (Combs & Onwuegbuzie, 2010). The analysis was carried out in three steps: first, each response was reviewed and labelled; next, the frequency of each label was noted using frequency counts; finally, responses were evaluated for relevance and meaning before being assigned to appropriate categories.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Faculty of Arts and Education Ethics Advisor Group, Deakin University (approval number HAE-17-220).

Results

Many parents provided extensive responses to the questions in this research. It is evident that the voluntary nature of the process led some to focus more on specific questions. However, the open-ended responses were crucial in shedding light on their perspectives.

The parents’ responses were organised into three areas of inquiry: perceptions of learning approaches; perceptions of learning priorities; and perceptions of influential factors. Related themes are presented under each area and summarised in respective tables, supported by example quotes. Additionally, associated figures quantify the themes in each table, indicating the number of parents expressing these views.

1. Perceptions of learning approaches

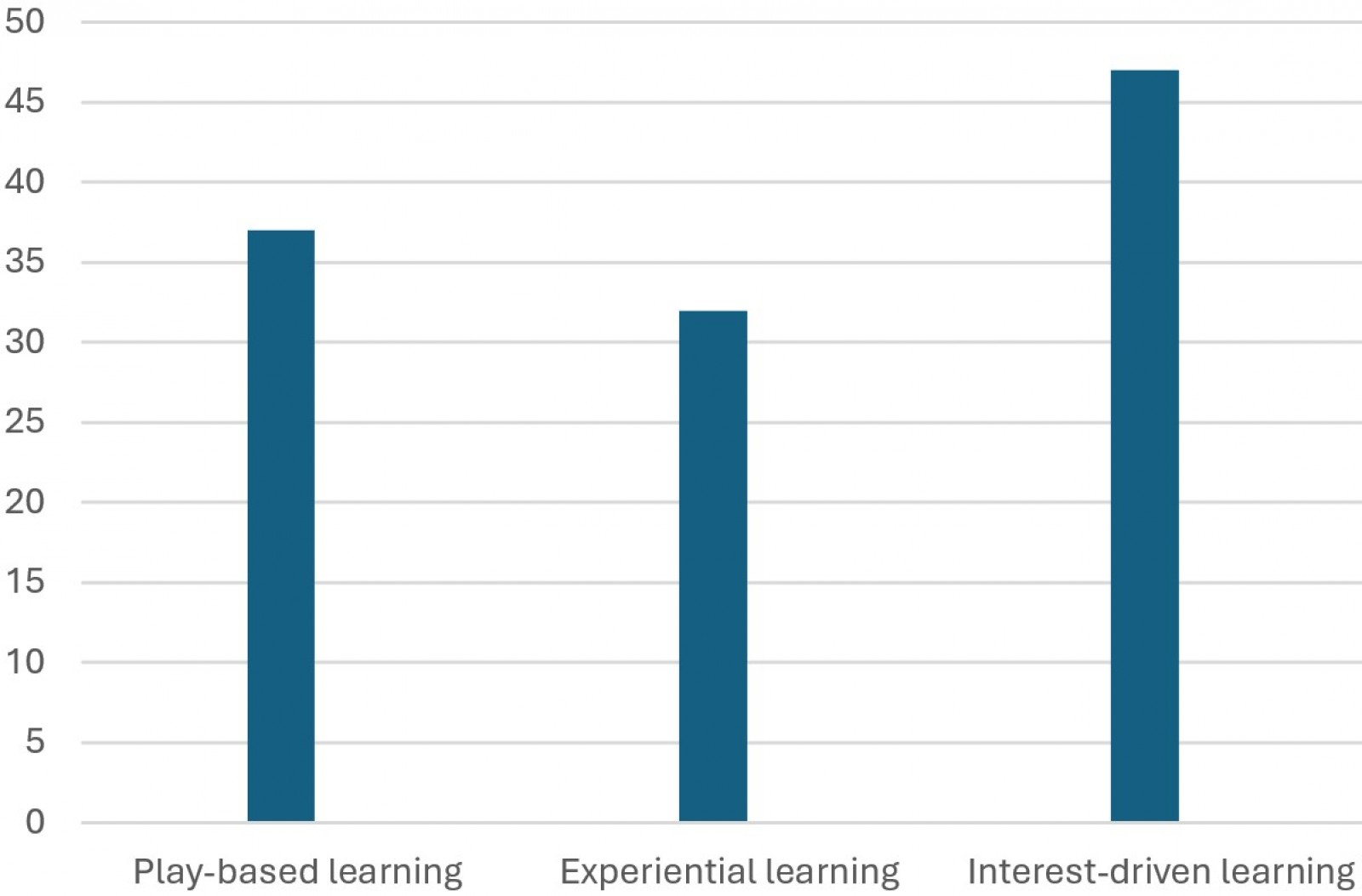

Three themes emerged in response to the inquiry on children’s learning approaches: children’s interests; play; and life experiences. These themes are presented in Table 1, with their frequency values illustrated in Figure 1. The results indicate that parents viewed children’s interests, play and life experiences as the primary drivers of learning. Of these, interests were rated the highest, followed closely by play and life experiences.

This emphasis on interests, play and life experiences aligns with the concept of learning as being, suggesting that parents perceive children’s learning as situated within everyday real-life contexts and tailored to children’s individual needs and interests. This perspective contrasts with traditional views of learning as a taught product or an experience requiring constant care and protection (Theobald et al., 2013). Moreover, parents’ perspectives are consistent with the educational practices outlined in the EYLF, which advocates for ‘play-based learning experiences using children’s interests, curiosities, and funds of knowledge’ (AGDE, 2022: p. 22).

Table 1. Summary of themes and example quotes that represent parents’ perceptions of learning approaches for young children

| Themes | Example quotes |

|---|---|

|

Play-based learning |

‘Play based learning has worked for my child’ ‘I believe that children learn through playful experiences’ |

|

Experiential learning |

‘Incidental- practical hands-on experiences are important’ ‘Use their hands and bodies and physically try things out’ |

|

Interest-driven learning |

‘A child learns more in the areas of his or her personal interests’ ‘I find my child being very focused when something interests him’ |

Figure 1. Quantity distribution of parents’ perceptions of learning approaches for young children

2. Perceptions of learning priorities

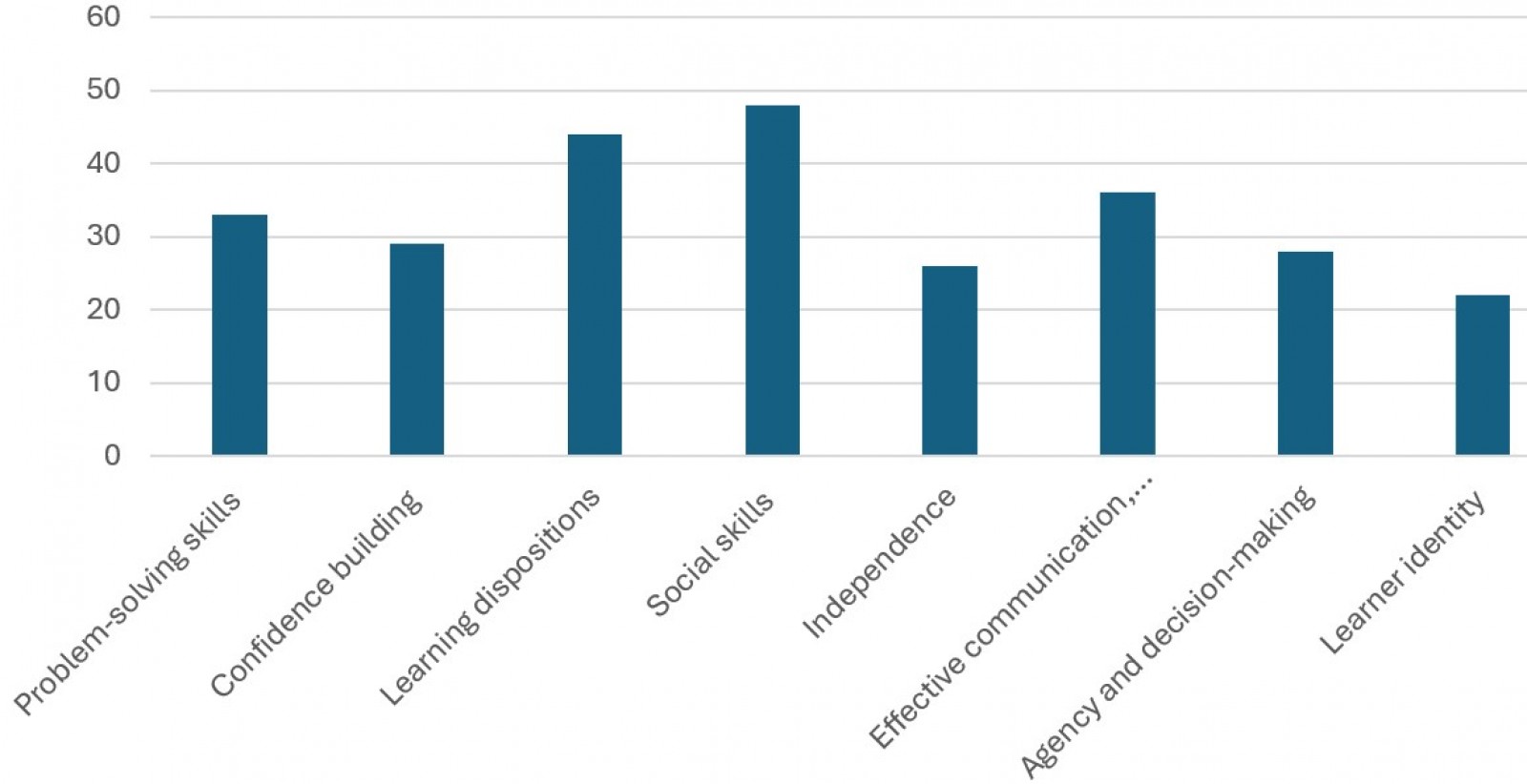

Parents’ descriptions of children’s learning priorities revealed eight overarching themes (Table 2). The results align with previous research conducted by Kwong et al. (2018), indicating that parents’ understanding of children’s learning encompasses a range of priorities that resonate with those highlighted by teachers and curriculum documents. As depicted in Figure 2, social skills emerged as the highest priority, receiving a score of 48, with 100% of parents mentioning it. This score surpassed the combined value attributed to various learning dispositions, such as persistence, determination and concentration, which were referenced in 44 out of 48 responses.

Analysing these themes through the concepts of being, belonging and becoming reveals how learning priorities mirror parents’ aspirations for their children’s development. For instance, responses like ‘having the courage to solve problems needs to be developed in young children’ illustrate parents’ emphasis on both current learning and future preparation, framing these priorities within the specific developmental stage of their young children.

The theme of ‘effective communication, language, numeracy, and literacy’ emerged as the third highest priority, with 36 responses. These developmental domains are closely associated with the concept of becoming, demonstrating parent’s expectations that children are equipped for the future.

Table 2. Summary of themes and example quotes that represent parents’ perceptions of children’s learning priorities

| Themes | Example quotes |

|---|---|

|

Problem-solving skills |

‘Having the courage to solve problems needs to be developed in young children’ |

|

Confidence building |

‘I want my child to build confidence and be confident’ |

|

Learning dispositions (e.g. persistent, concentration, determination and focus) |

‘In preschool, kids should develop learning attitudes of concentration, persistence and being focused’ |

|

Social skills (e.g. listening, kindness, open-mindedness, sharing, caring, tolerance, friendliness, teamwork, respect) |

‘I highly believe in the importance of social skills such as listening, good behaviours, such as caring and kindness and social cues’ |

|

Independence |

‘It’s the time to learn independence and do many things by themselves’ |

|

Effective communication, language, numeracy and literacy |

‘Communication and following instructions are areas of learning that young kids should focus on’ ‘I want my child to learn numbers, letters and speech in the kindergarten’ |

|

Agency and decision-making |

‘I think he needs to decide what and when he is going to learn, and take the initiatives’ |

|

Learner identity |

‘loves learning and actively learns what he learns and knows that learning is important’ |

Figure 2. Quantity distribution of parents’ perceptions of children’s learning priorities

3. Perceptions of influential factors

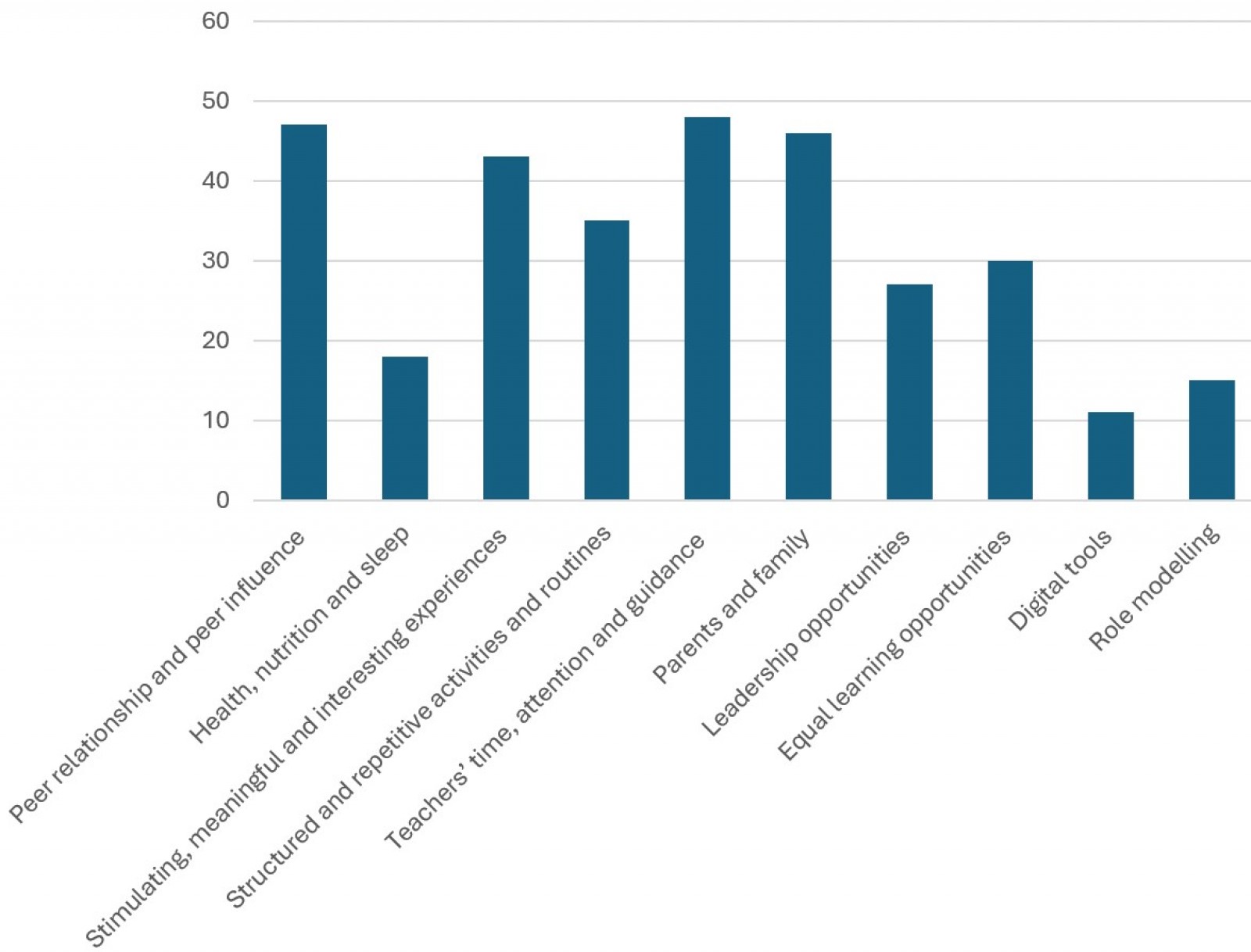

Ten themes emerged from parents’ responses regarding the influences on children’s learning, indicating that a wide range of factors were considered influential. As presented in Table 3, these factors included peers, parents, teachers, routines, learning activities, leadership opportunities, equal learning opportunities, digital tools, role modelling and children’s own health condition. The frequency values, illustrated in Figure 3, show that among these factors, teachers’ time, attention and guidance were rated the highest, with a perfect score of 48/48, closely followed by peers at 47/48 and parents and families at 46/48. Additionally, 43 parents emphasised the importance of stimulating, meaningful and interesting experiences, marking this as the fourth highest value among the ten themes.

These responses reflect parents’ awareness of various contributions to their children’s learning, both currently and on an ongoing basis. Synthesising these findings reveals that parents provided more detailed and nuanced insights into how children should learn. Each of these factors elaborates on the parents’ views regarding children’s interests, play and life experiences as integral to learning. Moreover, these results also demonstrate how parents’ focus on children’s being, becoming and belonging highlights the important roles of teachers, peers and parents. They provide useful insights into parents’ recognition of effective teachers’ practices that promote equal opportunities tailored to each child’s abilities and talents. In line with the EYLF emphasis on learning within the context of relationships, these results reveal intriguing parallels between parents’ knowledge and early childhood policies. They underline the synergy between parental understanding and teaching practices (McFarland & Laird, 2018), offering insights to reevaluate the perception of dichotomies between teachers and parents in children’s learning.

Table 3. Summary of themes and example quotes that represent parents’ perceptions of the factors that influence children’s learning

| Themes | Example quotes |

|---|---|

|

Peer relationship and peer influence |

‘Positive peer relationship with close friends makes a big difference in a child‘s learning and growth‘ ‘I think kids need to socialize with their peers and be able to compare themselves with others‘ |

|

Health, nutrition and sleep |

‘Having a good health, sleeping and eating well and a smooth toilet training process all help with the learning and growth‘ |

|

Stimulating, meaningful and interesting experiences |

‘Anything stimulating, meaningful that would capture her interest and ignite her curiosity‘ |

|

Structured and repetitive activities and routines |

‘Doing structured activities over and over again‘ |

|

Teachers‘ time, attention and guidance |

‘To be identified and called upon to contribute and encouraged to speak as my child is anxious in groups‘ ‘It is important for every child to have one on one time with grown ups and playing and learning with other kids‘ ‘If the adults around him are interested, he wants to know everything about it‘ ‘Kids learn well from those who have the time to sit and show how to do it‘ ‘Guidance by a teacher helps to ensure all children express their point of view‘ |

|

Parents and family |

‘Home environment reflects a child‘s learning abilities‘ ‘I think learning should start at home. Kindergarten and school should help parents to teach children‘ |

|

Leadership opportunities |

‘There should be opportunities for each child to lead a group at times, devise an activity, having an input in various stages of the learning activity‘ |

|

Equal learning opportunities |

‘Every child has different strengths and abilities and they should be recognised‘ |

|

Digital tools |

‘In today‘s world, lots of other things, such as TV and digital items are influencing children‘s learning. They can be good or bad‘ |

|

Role modelling |

‘A young child learns well if there are good models around him’ |

Figure 3. Quantity distributions of parents’ perceptions of the various influences on childen’s learning

Discussion and implications

For the past 15 years, the Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF) has been a central focus in Australian early years education, generating a substantial body of scholarly literature exploring its conceptual underpinnings and practical applications. Despite this, there has been a noticeable absence of research utilising the Framework to investigate parents’ understanding of children’s learning, particularly within the context of its defining concepts: belonging, being and becoming. The present study addresses this gap in the literature by examining such parental perspectives.

The study confirms previous research indicating that parents possess a comprehensive understanding of how and what young children learn, along with clear expectations for children’s ongoing development (Kwong et al., 2018). Their responses highlight key aspects of early childhood education, including the development of children’s knowledge, skills, desirable learning dispositions and various influential factors. While the study did not assess how parents acquired their knowledge, it is possible that children’s experiences in early childhood services were an important catalyst for their parents’ understanding. As noted by Spiteri (2020), the notion that parents solely shape their children is outdated; in today’s society, children’s experiences at home and outside the home significantly influence their parents.

The concepts of belonging, being and becoming are fundamental to the Australian early childhood curriculum, collectively contributing to the holistic development of each child and emphasising the importance of an integrated approach to early childhood education (AGDE, 2022). This study investigated parents’ perspectives on children’s learning in relation to these concepts. Upon analysing the themes, it became evident that the ideas of belonging, being and becoming were all reflected in parents’ viewpoints. Notably, the concept of being – which focuses on ‘a time to be, to seek and make meaning of the world’ (p. 6) – was the most frequently mentioned. This suggests that parents placed a strong emphasis on their children’s identity, choices and wellbeing, while also recognising the importance of social connections and learning trajectories.

The parents in this study were articulate in expressing their understandings and expectations of children’s learning in early childhood education. Contrary to concerns that parents might be academically demanding, disengaged or overprotective, the results of this study provide positive evidence of commonalities in understanding and expectations of children’s learning between early childhood policies and parents.

Of significance in the findings in this study is the need for early childhood practitioners to leverage parents’ knowledge and input, recognising them as valuable resources. In Australian early childhood services, teacher–parent cooperation most commonly takes place through formal and informal meetings. Rouse and O’Brien (2017) reported that teachers’ interactions with parents were often standardised rather than reciprocal and mutual. Similarly, Murphy et al. (2021) found in their study about parents’ views of teacher–parent practices, parents did not feel like partners in their interactions with teachers and felt that information sharing was inadequate. According to Murphy et al. (2021), educators, being in a position to build quality parent–educator relationships, might perceive this as emphasising their expert status. As noted by Rouse and O’Brien (2017), ‘while the teacher was meeting identified performance standards, a true partnership underpinned by mutuality and reciprocity was not evident in the relationships between the teacher and the families’ (p. 45).

The present study highlights that parents possess a comprehensive understanding of how and what their children learn, which could largely align with teachers’ perspectives. Teachers are therefore encouraged to integrate parent engagement as a natural part of their pedagogies, rather than viewing it as a required practice that necessitates deliberate arrangements and preparation on how to communicate with parents to reach common ground. The expectation that teachers, as professionals, should collaborate with parents often overlooks the critical role parents play in fostering equal contributions. In educational policies such as the EYLF, while strong messages about valuing and respecting parental knowledge have been conveyed, references to integrating this knowledge are often omitted, from which it can be inferred that supporting children’s learning is mainly the teachers’ professional responsibility.

The results discussed in this research reflect that it is important to consider adapting pedagogical strategies and policy aspirations to cultivate relationships that fully capitalise on parents’ position as children’s first teachers and include them as equal contributors to children’s learning. Integrating parents’ knowledge into teaching practice would signify a step towards genuinely acknowledging the value of parents’ ‘unprofessional’ knowledge, thereby creating spaces for mutual input into children’s learning and potentially leading to the development of effective approaches. Parents in this study acknowledged the significance of their own role in children’s learning, viewing themselves as one of the key influences alongside teachers and children’s peers, which provides positive encouragement for teachers to partner with them.

Conclusions

Based on a dataset of 48 survey responses, this study has illuminated the perceptions and expectations of Australian parents regarding young children’s learning and development. Through the lens of belonging, being and becoming, the defining concepts of the Early Years Learning Framework, this research explored children’s learning priorities, social positions and developmental trajectory from parents’ perspectives. Ultimately, the study revealed that what and how children learn have been viewed both as markers of a distinctive phase of childhood and as indicators of holistic development. This result echoes the emphasis in the EYLF on the interrelated and overarching nature of children’s learning, demonstrating that parents’ understanding largely aligns with policy perspectives.

This study involved a focused analysis of a small subset of data from three early childhood services, with minimal exploration of parents’ backgrounds, which constrained its scope. Although information about parents’ education levels was collected, the study primarily treated parents as a cohesive cohort rather than conducting a detailed analysis of parental variables. Future research could investigate how perceptions vary across different education levels among parents. It is acknowledged that incorporating more diverse data is necessary to broaden the focus and would lead to more comprehensive and large-scale findings. Despite the limitation, the themes generated provide a useful starting point for early childhood teachers when considering, planning and implementing cooperative practices with parents. In particular, the results demonstrate parents’ understanding of children’s holistic development in early childhood education, which could serve as a positive and affirming stimulus for teachers’ engagement with them.

References

Australian Government Department of Education (AGDE). (2022). Belonging, being and becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (V2.0). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council. acecqa.gov.au https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/EYLF-2022-V2.0.pdf

Combs, J. P., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2010). Describing and illustrating data analysis in mixed research. International Journal of Education, 2(2). shsu-ir.tdl.org https://shsu-ir.tdl.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/d2d78c3d-492f-4a6e-a3a4-278ce4f0273e/content

Gadsden, V., Ford, M., & Breiner, H. (2016). Parenting matters: Supporting parents of children aged 0–8. Washington, DC, USA: The National Academies Press. DOI https://doi.org/10.17226/21868 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27997088

Jackson, J. (2021). Developing early childhood educators with diverse qualifications: The need for differentiated approaches. Professional Development in Education, 49(5), 812–826. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1876151

Jeong, J., Franchett, E., de Oliveira, C., Rehmani, K., & Yousafzai, A. (2021). Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 18(5), e1003602. DOI https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003602 PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33970913

Knaus, M. (2015). ‘Time for being’: Why the Australian Early Years Learning Framework opens up new possibilities. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 13(3), 221–235. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X14538601

Kuby, C., & Vaughn, M. (2015). Young children's identities becoming: Exploring agency in the creation of multimodal literacies. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 15(4), 433–472. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798414566703

Kwong, E., Lam, C., Li, X., Chuang, K., Cheung, R., & Leung, C. (2018). Fit in but stand out: A qualitative study of parents' and teachers' perspectives on socioemotional competence of children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 44, 275–287. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.02.018

Leggett, N., & Ford, M. (2016). Group time experiences: Belonging, being and becoming through active participation within early childhood communities. Early Childhood Education, 44, 191–200. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0702-9

McFarland, L., & Laird, S. (2018). Parents’ and early childhood educators' attitudes and practices in relation to children's outdoor risky play. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46, 159–168. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-017-0856-8

Mulhall, S. (2000). Heidegger and being and time. London, UK: Routledge.

Murphy, C., Matthews, J., Clayton, O., & Cann, W. (2021). Partnership with families in early childhood education: Exploratory study. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 46(1), 93–106. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939120979067

Peers, C., & Fleer, M. (2014). The theory of ‘belonging’: Defining concepts used within Belonging, Being and Becoming-The Australian Early Years Learning Framework. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 46(8), 914–928. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2013.781495

Raban, B. (2011). A new era in early years learning. Research Developments, 26(26). research.acer.edu.au https://research.acer.edu.au/resdev/vol26/iss26/3/

Rouse, E., & O’Brien, D. (2017). Mutuality and reciprocity in parent-teacher relationships: Understanding the nature of partnerships in early childhood education and care provision. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 42(2), 45–52. DOI https://doi.org/10.23965/AJEC.42.2.06

Spiteri, J. (2020). Too young to know? A multiple case study of child-to-parent intergenerational learning in relation to environmental sustainability. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 14(1), 61–77. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408220934649

Strycharz-Banaś, A., Dalli, C., & Meyerhoff, M. (2020). A trajectory of belonging: Negotiating conflict and identity in an early childhood centre. Early Years, 42(4–5), 512–527. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2020.1817871

Sumsion, J., & Wong, S. (2011). Interrogating ‘belonging’ in Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 12(1), 28–45. DOI https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2011.12.1.28

Theobald, M., Cobb-Moore, C., & Irvine, S. (2013). A snapshot of 40 years in early childhood education and care through oral histories. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(4), 107–115. DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911303800415

Uprichard, E. (2008). Children as ‘being and becomings’: Children, childhood and temporality. Children and Society, 22(4), 303–313. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2007.00110.x